My Imprisonment

and the First Year of Abolition Rule

at Washington:

Electronic Edition

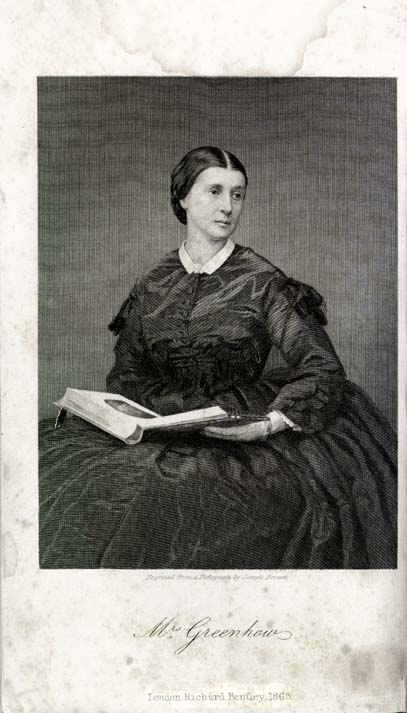

Mrs. Greenhow, Rose O'Neal, 1814-1864

Funding from the Library of

Congress/Ameritech National Digital Library

Competition

supported the electronic publication of this

title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Heather Bumbalough

Images scanned by

Jennifer Stowe

Text encoded by

Kathleen Feeney and Natalia Smith

First edition, 1998

ca. 550K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

1998.

Call number E608.G8 1863 (Davis Library, UNC-CH)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting

the American South, or, The Southern Experience in

19th-century America.

Any hyphens occurring in

line breaks

have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has

been joined to the preceding line.

All quotation marks and

ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left

quotation marks are encoded

as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left

quotation marks are encoded

as ' and ' respectively.

Indentation in lines has

not been preserved.

Running titles have not

been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text

using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell

check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings,

19th edition, 1996

-

1998-06-26,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

1998-06-04,

Kathleen Feeney

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 1998-05-10,

Heather Bumbalough

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

MY IMPRISONMENT

AND THE

FIRST YEAR OF ABOLITION RULE

AT WASHINGTON.

BY

MRS. GREENHOW.

LONDON:

RICHARD BENTLEY,

PUBLISHER IN ORDINARY TO HER MAJESTY.

1863.

LONDON

Printed BY SPOTTISWOODE AND CO.

NEW-STREET SQUARE

Page iii

Dedication.

I RESPECTFULLY DEDICATE THESE PAGES

TO THE

BRAVE SOLDIERS

WHO HAVE FOUGHT AND BLED

IN

THIS OUR GLORIOUS STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOM.

ROSE GREENHOW.

London:

Nov.

6, 1863.

Page v

CONTENTS.

- CHAPTER I.

INTRODUCTION . . . . . PAGE 1

- CHAPTER II.

ON TO RICHMOND!

My Arrest - Lincoln's Arrival - Scotch Cap and Cloak - His

Election an Invasion of Southern Rights - Order for the

Advance of the Grand Army into Virginia - Its Departure

- Battle of Manassas - Defeat and Rout - Its Return to

Washington - Demoralisation - Quarrels between Executive,

Legislative and Military - Panic . . . . . 11

- CHAPTER III.

PANIC AT WASHINGTON.

Attack upon the Prisoners - United States Troops obliged to

protect them - My Visit to the Prison - Mr. Commissioner

Wood - Charles Sumner - Dismemberment of Virginia -

Admission of Senators - Reign of Terror - Determination to

remove Scott - Elevation of M'Clellan . . . . . 25

Page vi

- CHAPTER IV.

DAYS OF TRIAL.

My Arrest - Search and Occupation of my House - Examination

of my Papers - Miss Mackall - Mr. Calhoun - Destruction

of my Cipher - Female Detective - Search of my Person -

Resolution to fire the House - Arrest of Casual Visitors -

Inebriation of the Guard - Outrage - Tactics of my Gaolers

- Andrew J. Porter . . . . . PAGE 52

- CHAPTER V.

REIGN OF TERROR.

Abolition Effort to poison President Buchanan - Destruction of my

Papers - Reward for my Cipher - Intercepting Despatches -

Mr. Seward - Personal Danger - Mr. Davis - Effort to bribe

me - General Butler - Yankee Publications - Other

Prisoners - Spoliation - Detective Police give place to

Military Guards - Miss Mackall - Illness of my Child -

Dr. Stewart - Prison Life - The Spy Applegate - Mr.

Stanton - Judge Black and R. J. Walker - Foul

Outrage - Yankee Policy - Petty Annoyances . . . . . 73

- CHAPTER VI.

OLLA PODRIDA.

The Great Armada - My Anxiety - Its Destination revealed by

Seward - Information sent to Richmond - Dr. Gwin -

Equinoctial Gales - Proposition to escape - Insult to

Ministers of the Gospel - Query of Provost-Marshal - The

Mother of Jackson - The First Victim of the War of

Aggression - Visit from Members of my Family - Colonel

Ingolls - Letter to Mr. Seward . . . . . 108

Page vii

- CHAPTER VII.

NEW TRIALS.

Abolition Difficulties - M'Clellan - Scott - Fremont brought

forward - F. P. Blair - Reviews and Sham Battles - Seward's

Policy - Destruction of Civil Rights - Armed Occupation of

Maryland - Elections at the Point of the Bayonet -

Despotism in Baltimore - My own Lot - Miss Mackall's

Visit to Lincoln and Porter - Her Illness and Desire to see me -

Application to Lincoln - His Refusal - Death of Miss Mackall

- My own Illness - Dr. M'Millen - Peculations of Cameron -

Sent to Russia - Congressional Committee . . . . . PAGE 125

- CHAPTER VIII.

FREMONT AND OTHER THINGS.

Fremont - Fremont Père - His Education - His Marriage -

Career in California - His Trial - Dismissal from the U.S.

Army - Senator for California - Retirement to Private Life -

Appearance as Candidate for President - The Marriposa -

Financial Schemes - Defeat for President - Relapse -

Reappearance - Charges against him - Mrs. Fremont and

F. P. Blair - Removal as Chief of the Army of the West -

Halleck - Myself - Trials - M'Clellan - Public Archives

. . . . . 141

- CHAPTER IX.

DIABLERIE.

Petty Annoyances - My Letters objected to - My Protest -

'New York Herald' - Judge-Advocate Key - What he said -

Christmas-day - Warning - Other Prisoners - Comic Scenes -

Detective Police - Severe Ordeal - Seizure of my Journal,

&c. - Writing Materials prohibited by Order of

General Porter . . . . . 161

Page viii

- CHAPTER X.

RECORD OF FACTS.

My second Letter to Seward - Our Commissioners - At my own

House - Seward's Sketch of John Brown - On Arts -

Seward's Reveries - Bribery and Corruption . . . . . PAGE 179

- CHAPTER XI.

TRIALS AND DANGER.

Stanton in Power - Mr. Buchanan - Ordinances - 'New York

Herald' - M'Clellan's Humility - Ministerial Assumption -

Financiering of Secretary Chase - New York Brokers and

Bankers - Mrs. Lincoln - Her Shopping Toilette - My

Removal to the Old Capitol Prison - Lieutenant Sheldon -

Newspaper Correspondents - Mr. Calhoun's Opinions - My

Cell - Dr. Stewart again - Extracts from Journal kept in the

Old Capitol - Nuisance - My Protest - My Child -

Disgusting Sights - Protest. . . . . 195

- CHAPTER XII.

PROGRESS OF EVENTS.

Congressional Committee - Dame Rumour and Mrs. Lincoln -

'Herald' on Mrs. Lincoln - M'Clellan - Policy of

Administration towards him - Chance Prophecy - My Yankee

Visitors - Abolition Policy, &c. - Southern Chivalry -

'Richmond Examiner' - President Davis - 'On to Richmond,'

3rd - Estimate of our Forces - Expenditure - Pressure of

Public Opinion - Reinforcements - Festive Scenes - Ball at

the White House - Mrs. Lincoln's Toilette - General

Magruder - M'Clellan's Ideas - Policy of the Government -

Evacuation of Yorktown by Johnson - President Davis's

Coachman, and what he said - Northern Credulity and Venality

. . . . . 225

Page ix

- CHAPTER XIII.

HOPES AND FEARS.

Illness of my Child - Application for Medical Attendance - Dr.

Stewart - Protest against his Insolence - General Johnson -

Change of Programme - Homesteads in the South - Senator

Wilson - Stanton's Order, &c. - My Letter announcing it -

Police-court - Letter to Stanton - General Wordsworth - His

Order - Vexations and Annoyances - The Officers of the

Guard - Extraordinary Drive - General

Commotion . . . . . PAGE 243

- CHAPTER XIV.

FURTHER DEVELOPEMENT.

Visit of United States Commissioners - Their Objects -

Conversation - My Child - General Dix - Insolence of Dr.

Stewart - Rebuke to him - Stanton's Policy - Cause of his

Appointment - His Political Programme - Lincoln and

Abolition of Slavery - Demoniacal Intentions - Appearance

before the Commissioners - Picture of Desolation - Sketch of

Commissioners - The Object of the Commission -

Gentlemanly Conduct of the Commissioners - Letter to Mrs.

S. A. Douglas in answer to hers - Anxieties - Letter to General

Wordsworth - Murder of Lieutenant Wharton - Letter to

General Wordsworth . . . . . 260

- CHAPTER XV.

RENEWED ANXIETIES.

Visit of Hon. Mr. Ely - Cause of my Detention - New York

Paper - Application to visit me refused - Tedium of Prison

Life - The Guard - The Female Prisoners - Captain Higgins

- My Child's Health - Dr. Miller - Federal Officers

Page x

- Ex-Governor Morton - Correspondence - Anxieties

- Fate of New Orleans - Order No. 28 of General Butler -

Caleb Cushing - Senator Bayard - Fate of Norfolk -

Murder of Stewart - Examination - Yankee Panic - Senatorial

Committee - Disagreeable Rumours - Correspondence with Wood

relative to my Papers - Gloom - Cheering

News - Announcement of Departure for the South - Arrival

in Baltimore - Kind Friends - General Dix - En Route

- Arrival in Richmond - The President - Aspect of

Richmond . . . . . PAGE 288

- CHAPTER XVI.

MAN INCAPABLE OF SELF-GOVERNMENT.

The American Revolution - Slavery not the Cause of it -

Political Supremacy - Ex-President Fillmore's, Daniel

Webster's, Lord John Russell's, and R. J. Walker's Opinions on

the Subject - Non-intervention the best Policy, &c. 325

My Arrest - Lincoln's Arrival - Scotch Cap and Cloak - His Election an Invasion of Southern Rights - Order for the Advance of the Grand Army into Virginia - Its Departure - Battle of Manassas - Defeat and Rout - Its Return to Washington - Demoralisation - Quarrels between Executive, Legislative and Military - Panic . . . . . 11

Attack upon the Prisoners - United States Troops obliged to protect them - My Visit to the Prison - Mr. Commissioner Wood - Charles Sumner - Dismemberment of Virginia - Admission of Senators - Reign of Terror - Determination to remove Scott - Elevation of M'Clellan . . . . . 25

Page vi

My Arrest - Search and Occupation of my House - Examination of my Papers - Miss Mackall - Mr. Calhoun - Destruction of my Cipher - Female Detective - Search of my Person - Resolution to fire the House - Arrest of Casual Visitors - Inebriation of the Guard - Outrage - Tactics of my Gaolers - Andrew J. Porter . . . . . PAGE 52

Abolition Effort to poison President Buchanan - Destruction of my Papers - Reward for my Cipher - Intercepting Despatches - Mr. Seward - Personal Danger - Mr. Davis - Effort to bribe me - General Butler - Yankee Publications - Other Prisoners - Spoliation - Detective Police give place to Military Guards - Miss Mackall - Illness of my Child - Dr. Stewart - Prison Life - The Spy Applegate - Mr. Stanton - Judge Black and R. J. Walker - Foul Outrage - Yankee Policy - Petty Annoyances . . . . . 73

The Great Armada - My Anxiety - Its Destination revealed by Seward - Information sent to Richmond - Dr. Gwin - Equinoctial Gales - Proposition to escape - Insult to Ministers of the Gospel - Query of Provost-Marshal - The Mother of Jackson - The First Victim of the War of Aggression - Visit from Members of my Family - Colonel Ingolls - Letter to Mr. Seward . . . . . 108

Page vii

Abolition Difficulties - M'Clellan - Scott - Fremont brought forward - F. P. Blair - Reviews and Sham Battles - Seward's Policy - Destruction of Civil Rights - Armed Occupation of Maryland - Elections at the Point of the Bayonet - Despotism in Baltimore - My own Lot - Miss Mackall's Visit to Lincoln and Porter - Her Illness and Desire to see me - Application to Lincoln - His Refusal - Death of Miss Mackall - My own Illness - Dr. M'Millen - Peculations of Cameron - Sent to Russia - Congressional Committee . . . . . PAGE 125

Fremont - Fremont Père - His Education - His Marriage - Career in California - His Trial - Dismissal from the U.S. Army - Senator for California - Retirement to Private Life - Appearance as Candidate for President - The Marriposa - Financial Schemes - Defeat for President - Relapse - Reappearance - Charges against him - Mrs. Fremont and F. P. Blair - Removal as Chief of the Army of the West - Halleck - Myself - Trials - M'Clellan - Public Archives . . . . . 141

Petty Annoyances - My Letters objected to - My Protest - 'New York Herald' - Judge-Advocate Key - What he said - Christmas-day - Warning - Other Prisoners - Comic Scenes - Detective Police - Severe Ordeal - Seizure of my Journal, &c. - Writing Materials prohibited by Order of General Porter . . . . . 161

Page viii

My second Letter to Seward - Our Commissioners - At my own House - Seward's Sketch of John Brown - On Arts - Seward's Reveries - Bribery and Corruption . . . . . PAGE 179

Stanton in Power - Mr. Buchanan - Ordinances - 'New York Herald' - M'Clellan's Humility - Ministerial Assumption - Financiering of Secretary Chase - New York Brokers and Bankers - Mrs. Lincoln - Her Shopping Toilette - My Removal to the Old Capitol Prison - Lieutenant Sheldon - Newspaper Correspondents - Mr. Calhoun's Opinions - My Cell - Dr. Stewart again - Extracts from Journal kept in the Old Capitol - Nuisance - My Protest - My Child - Disgusting Sights - Protest. . . . . 195

Congressional Committee - Dame Rumour and Mrs. Lincoln - 'Herald' on Mrs. Lincoln - M'Clellan - Policy of Administration towards him - Chance Prophecy - My Yankee Visitors - Abolition Policy, &c. - Southern Chivalry - 'Richmond Examiner' - President Davis - 'On to Richmond,' 3rd - Estimate of our Forces - Expenditure - Pressure of Public Opinion - Reinforcements - Festive Scenes - Ball at the White House - Mrs. Lincoln's Toilette - General Magruder - M'Clellan's Ideas - Policy of the Government - Evacuation of Yorktown by Johnson - President Davis's Coachman, and what he said - Northern Credulity and Venality . . . . . 225

Page ix

Illness of my Child - Application for Medical Attendance - Dr. Stewart - Protest against his Insolence - General Johnson - Change of Programme - Homesteads in the South - Senator Wilson - Stanton's Order, &c. - My Letter announcing it - Police-court - Letter to Stanton - General Wordsworth - His Order - Vexations and Annoyances - The Officers of the Guard - Extraordinary Drive - General Commotion . . . . . PAGE 243

Visit of United States Commissioners - Their Objects - Conversation - My Child - General Dix - Insolence of Dr. Stewart - Rebuke to him - Stanton's Policy - Cause of his Appointment - His Political Programme - Lincoln and Abolition of Slavery - Demoniacal Intentions - Appearance before the Commissioners - Picture of Desolation - Sketch of Commissioners - The Object of the Commission - Gentlemanly Conduct of the Commissioners - Letter to Mrs. S. A. Douglas in answer to hers - Anxieties - Letter to General Wordsworth - Murder of Lieutenant Wharton - Letter to General Wordsworth . . . . . 260

Visit of Hon. Mr. Ely - Cause of my Detention - New York Paper - Application to visit me refused - Tedium of Prison Life - The Guard - The Female Prisoners - Captain Higgins - My Child's Health - Dr. Miller - Federal Officers

Page x

- Ex-Governor Morton - Correspondence - Anxieties - Fate of New Orleans - Order No. 28 of General Butler - Caleb Cushing - Senator Bayard - Fate of Norfolk - Murder of Stewart - Examination - Yankee Panic - Senatorial Committee - Disagreeable Rumours - Correspondence with Wood relative to my Papers - Gloom - Cheering News - Announcement of Departure for the South - Arrival in Baltimore - Kind Friends - General Dix - En Route - Arrival in Richmond - The President - Aspect of Richmond . . . . . PAGE 288

The American Revolution - Slavery not the Cause of it - Political Supremacy - Ex-President Fillmore's, Daniel Webster's, Lord John Russell's, and R. J. Walker's Opinions on the Subject - Non-intervention the best Policy, &c. 325

Page 1

MY IMPRISONMENT

AND THE

FIRST YEAR OF ABOLITION RULE

AT WASHINGTON.

CHAPTER I.

INTRODUCTION.

WHETHER a faithful record of my long and humiliating

imprisonment at Washington, in the hands of

the enemies of my country, will prove as interesting to

the public as my friends assure me it is to

them, I know not. It is natural for those who have suffered

captivity to exaggerate the importance and

interest of their own experiences; yet I should not

venture upon publishing these notes and sketches

merely as a narrative of indignities heaped upon myself

personally. It is hoped that the story may

excite more than a simple feeling of indignation or

commiseration, by exhibiting somewhat of the

intolerant spirit in which the present crusade against

the liberties of sovereign States was undertaken,

and somewhat of the true character of that race of

people who insist on

Page 2

compelling us by force to live with them in bonds of fellowship and union.

I had been long a resident of Washington before the secession of the Confederate States, and, from my intimate acquaintance with public men and public measures under the old government, had peculiar and exceptional means of watching the progressive development of the designs of these Leaders of opinion in the Federal States, which, as I had long foreseen, would necessarily end in forcing on a separation.

Much of my information upon this subject had been derived from the intercourse of society in the Federal capital; and would therefore have been unsuitable to be made public, if the relations of the North and the South had continued as they used to be - subjects of political discussion and party contest. But the Federal leaders have now carried the matter far beyond this point. After repeated and intolerable aggression upon the rights of these States - accompanied and aggravated by an insulting tone of moral superiority, until a union with such communities was no longer to be endured by any high-spirited people - they at length stirred up a furious and desolating war. For two years a torrent of blood has flowed between their people

Page 3

and my people. The noble State of Virginia, with which I am most nearly connected, has been devastated by hosts of barbarous invaders - always overthrown indeed in the field before Southern valour, but always destroying and plundering where they found the country unprotected; whilst my own dear native State of Maryland has been subject to a still more stinging and maddening oppression, in the utter destruction of all her liberties, and in the establishment of a brutal and vulgar military despotism, which has reduced the gallant old State to the debased condition of Poland or Venetia; and such 'order reigns in Baltimore,' as that moral death which tyrants call 'order' in Warsaw or in the beautiful City of the Sea.

To me, therefore, the days of my former abode in Washington seem to belong almost to another state of being. That time - when I, in common with all our people, looked up with pride and veneration to the banner of the stars and stripes - appears to be now with the years before the Flood. I look back to the scenes of that period through a haze of blood and horror. Those men whom I once called friends - who have broken bread at my table - have since then stirred up and hounded on host after host of greedy invaders, and precipitated them upon the beloved

Page 4

valleys where my kindred had their peaceful homes. Many who were dear to me have been slain, or maimed for life, fighting in defence of all that makes life of value. Instead of friends, I see in those statesmen of Washington only mortal enemies. Instead of loving and worshipping the old flag of the stars and stripes, I see in it only the symbol of murder, plunder, oppression, and shame! and, like every other faithful Confederate, I dwell with delight on the many glorious fields where this dishonoured standard has gone down before the stainless battle-flag of the Confederacy.

In short, two years of terrible war, equivalent, an age of quiet life, have passed through the existence of us all, leaving a deep and ineffaceable track. Between us and those former friends there is a gulf deep and wide as eternity; and under these circumstances I have felt myself at liberty to be much more unreserved in the narrative of my personal recollections: suppressing, in fact, nothing which I thought would be either interesting or useful to my Confederate countrymen - except only when reserve was dictated by self-respect, or by the duty of avoiding disclosures which might compromise the safety of certain Federal officers, whom I induced without scruple as will be more fully seen in the

Page 5

following pages, to furnish me with information, even in my captivity, which information I at once communicated with pride and pleasure to General Beauregard, then commanding the Confederate forces near Washington. Whatever may be thought of the conduct of these Federal officers in betraying to an avowed enemy secrets material to their own Government, it will readily be admitted that after having made this use of them I should not have been justified in naming them, or affording a clue by which they could be discovered.

If, in detailing conversations which passed either with me or in my presence, before or after my arrest, I may be thought to have exhibited too great bitterness, it is hoped that the circumstances under which I found myself may plead my excuse. It will be seen that I was well aware from an early period of the dark designs of the Abolition leaders at Washington, and that while they were holding publicly the language of patriotic zeal for the constitution and the law, they were already meditating, and preparing, all the dreadful scenes of lawless outrage and spoliation which have since that time rendered their names odious to the whole world It was well known to me what fate they were reserving for my own native State, and what diabolical

Page 6

agencies they were setting to work over all the country, both to destroy the Confederate States and to crush out the liberties of the North. The chief projectors of all these horrors, too, were well aware that I knew their plans and machinations intimately; and that, weak woman as I was, I possessed both the means and the spirit to throw serious obstacle in their way. Hence the keen and jealous surveillance by which my every motion was observed and noted, even long before my arrest. Hence, also, the useless series of torments and provocations to which I was subjected - the changes in my place of imprisonment, and the many attempts to entrap me into a betrayal of myself or the Confederate cause. Hence the long and wearisome captivity, to break my spirit, or goad me into undignified bursts of indignation - in all of which I trust I may flatter myself that they signally failed. Satisfied thoroughly of the justice and sacredness of our great cause, thinking only of the gallant struggle into which my kindred had thrown themselves, I was enabled, not only to 'possess my own soul' and keep my own counsel, but also to establish and maintain a continuous correspondence with Virginia, and reveal certain contemplated military movements of enemy in time to have them thwarted by our

Page 7

generals. For this I do not desire to take any special credit in the eyes of the public. I only performed my duty, and have already been gratified by the thanks of those who best can judge of the services which I endeavoured to render; and the matter is mentioned here merely as one of the reasons why it has been thought that a narrative furnished by one who enjoyed such opportunities of observation may be found not uninteresting.

It may be that the language which was sometimes extorted from me in conversation, or some of the remarks now found in my book, are more bitterly vituperative and sarcastic, than in ordinary times, and upon ordinary subjects, would be becoming in the personal narrative of a woman. Those who may think so are only entreated, before they judge, to endeavour to imagine themselves in my position - subject to the stinging indignities of a Washington prison, having to encounter sometimes the vicious taunts of vulgar guards, sometimes the treacherous warnings or counsels of politicians pretending to be my friends; a little daughter, too, always before my eyes, torn from the peaceful delights of home, and the flowery path of girlhood, and forced to witness the hard realities of prison-life, and hear the keys grating in dungeon locks. No wonder if my

Page 8

nature grew harsh and more vindictive, and if the scorn and wrath that was in my heart sometimes found vent by tongue or pen.

It was, above all things, when I thought of my own State of Maryland - where sleep the manes of my ancestors - that I burned with indignation in my prison. While the great State of Virginia, with her strong river frontier of the Potomac, was enabled to bid defiance to the utmost efforts of her enemies, it soon became evident that Maryland, penetrated by great bays and rivers, and with her very heart opened up to the naval forces of the enemy, would be, for the present at least, overpowered, and prevented from casting her lot openly and decisively with her sister States. I knew also that every genuine child of Maryland cherished in their souls but one feeling - one burning desire to share the destiny of their section, and to perish, if need be, in the glorious struggle; and could well imagine how so proud and refined a people would suffer and chafe to see themselves treated as vassals and serfs by a race they have always despised.

Yet the men were not so deeply to be pitied. They had always at least the resource of flinging themselves across the border, joining the Confederate service, and thus either opening a way to the redemption

Page 9

of their country, or at any rate meeting her oppressors on many a battle-field, and wreaking a righteous vengeance upon their heads. But the women of Maryland - the far-famed, delicately-nurtured, and universally-courted ladies of that fair State - they, whose slightest notice in days gone by was so dearly prized by Northern men - they, so essentially Southern in taste, and style, and association - to see their country ruled by hordes of the despised Yankees, and their haughty city tamed and cowering under the insolent sway of the coarsest of all human creatures! - to know that 'the tinkling of that little bell' at the State Department could tear the maiden from her mother's arms, to be dragged to the pollution of a Yankee prison! The thought was often almost maddening; and it may well be that my profound sympathy with my people has coloured with a deeper tinge of gloom my views of the whole field of action.

At all events, I have endeavoured in this sketch of my captivity to discharge a great duty. That duty was to contribute what I myself have seen and known of the history of the time. If the exposure therein made of the Yankee character, in the first year of its luxuriant and rampant development (after long compression in a condition of inferiority),

Page 10

shall add to the feeling of execration for such a race of people, and deepen the universal gratitude at the happy change which has severed us from them, and made it still more and more impossible that we can ever submit to any kind of political association with them again, then my poor narrative will not have been written in vain.

Page 11

CHAPTER II.

ON TO RICHMOND!

MY ARREST - LINCOLN'S ARRIVAL - SCOTCH CAP AND CLOAK - HIS ELECTION AN INVASION OF SOUTHERN RIGHTS - ORDER FOR THE ADVANCE OF THE GRAND ARMY INTO VIRGINIA - ITS DEPARTURE - BATTLE OF MANASSAS - DEFEAT AND ROUT - ITS RETURN TO WASHINGTON - DEMORALISATION - QUARRELS BETWEEN EXECUTIVE, LEGISLATIVE AND MILITARY - PANIC.

ON FRIDAY, August 23rd, in Washington City - the metropolis of this once free and happy land, the proud boast of which was that life, liberty, and property were protected by the law - I was made a prisoner in my own house, and subjected to an ordeal which must have been copied from the days of the Directory in France.

My blood boils when I think of it. But, for the benefit of all who may feel an interest in the subject, I will give a circumstantial account of an act which should shed renown upon the distinguished authors of it.

It is necessary for my purpose to make a brief

Page 12

résumé of the incidents of the few months preceding. I might even go back to the advent of the Scotch cap and cloak, but will content myself with an event quite as remarkable in the reign of the Abolition 'Irrepressible conflict chief,' whose shadow now darkens the chair of Washington.

As the allusion to the 'Scotch cap and cloak' may not be generally understood, I deem it advisable to furnish information on that head, as a means of explaining the modus operandi by which the Abolition leader entered the national Capitol.

He had been elected President by a strictly sectional majority, not having received one vote in the States south of Mason and Dixon's line - the great geographical line dividing North and South - arriving thereby at the very point in our political destiny which Washington, in his 'farewell address,' had foreshadowed as a cause for the dissolution of the Union.

During the heated sectional contest which resulted in the election of Mr. Lincoln by the Abolition party, they openly proclaimed 'the higher law doctrine,' and announced their determination, regardless of constitutional guarantees, to deprive the South of her sovereign equal rights, and to reduce her to a state of vassalage; for a feeling of bitter jealousy

Page 13

had been festering and strengthening in the Northern mind against her, on account of the superior statesmanship and intellect, which had always given her preeminence in the councils of the nation, and in the legislative assemblies.

In order to carry into effect this hostile determination to destroy the political importance of the South, they had seized upon what they conceived to be the vulnerable point in our domestic institution - well knowing that they could enlist the fanatical aid and sympathy of those who were ignorant, save theoretically, of that institution, and of the benign and paternal manner in which it was conducted in the South; having in view no object themselves of ameliorating the condition of the servile class, but to exterminate or drive them out, in order that their own pauper population might secure to themselves the superior advantages which were everywhere in the South monopolised by the slave population.

Denunciations were levelled against us by the poorer classes of the North as 'a pampered aristocracy,' for the reason they gave 'that a poor white man at the South was not as good as a negro.' And the negroes, I must confess, always arrogated to themselves this social superiority, for the bitterest

Page 14

insult they could offer each other was, 'You are no better than a poor white Yankee!'

The Abolition party were not, however, prepared for the firm and dignified bearing of the South, at the result of an election strictly sectional and avowedly subversive of the Constitution; and they believed, according to their own established precedent, that mob law would take the matter in hand, and summarily dispose of the candidate elect, or prevent his inauguration.

Excited and absurd discussions and plans were made at Washington and other places as to the means by which he should reach the capital. Lincoln had, however, formed a plan of his own, and, having far more reticence than had been ascribed to him by his partisans, executed it whilst these discussion were going on, and suddenly appeared at Washington, at six o'clock in the morning, under the disguise of a 'Scotch cap and cloak,' announcing himself with characteristic phraseology in the apartments of his sleeping Committee of Safety at Willard's Hotel with - 'Hillo! Just look at me! By jingo, my own dad wouldn't know me!'

On the morning of the 16th of July, the Government papers at Washington announced that the 'grand army' was in motion, and I learned from a

Page 15

reliable source (having received a copy of the order to M'Dowell) that the order for a forward movement had gone forth. If earth did not tremble surely there was great commotion amongst that class of the genus homo yclept military men. Officers and orderlies on horse were seen flying from place to place; the tramp of armed men was heard on every side - martial music filled the air; in short, a mighty host was marshalling, with all the 'pomp and circumstance of glorious war.' 'On to Richmond!' was the war-cry. The heroes girded on their armour with the enthusiasm of the Crusaders of old, and vowed to flesh their maiden swords in the blood of Beauregard or Lee. And many a knight, inspired by beauty's smiles, swore to lay at the feet of her he loved best the head of Jeff. Davis at least.

Nothing, nothing was wanting to render the gorgeous pageant imposing. So, with drums beating and flying colours, and amidst the shower of flowers thrown by the hands of Yankee maidens, the grand army moved on to the land of Washington, of Jefferson, of Madison, and Monroe; whilst the heartstricken Southerners who remained, did not tear their hair and rend their garments, but prayed on their knees that the God of Battles would award the victory to the just cause.

Page 16

In fear and trembling they awaited the result - hoping, yet fearing to hope. Time seemed to move on leaden wings. Imagination sounded in their ears the booming cannon, and many a time their hearts died within them at the sickening delay. Few had the hope which filled my own soul, or shared in its exultant certainty of the result. At twelve o'clock on the morning of the 16th of July, I despatched a messenger to Manassas, who arrived there at eight o'clock that night. The answer received by me at mid-day on the 17th will tell the purport of my communication - 'Yours was received at eight o'clock at night. Let them come: we are ready for them. We rely upon you for precise information. Be particular as to description and destination of forces, quantity of artillery, &c. (Signed) THOS. JORDON, Adjt.-Gen.' On the 17th I despatched another missive to Manassas, for I had learned of the intention of the enemy to cut the Winchester railroad, so as to intercept Johnson, and prevent his reinforcing Beauregard, who had comparatively but a small force under his command at Manassas.

On the night of the 18th, news of a great victory by the Federal troops at Bull Run reached Washington. Throughout the length and breadth of the city it was cried. I heard it in New York on Saturday,

Page 17

20th, where I had gone for the purpose of embarking a member of my family for California, on the steamer of the 22nd. The accounts were received with frantic rejoicings, and bets were freely taken in support of Mr. Seward's wise saws - that the rebellion would be crushed out in thirty days. My heart told me that the triumph was premature. Yet, O my God! how miserable I was for the fate of my beloved country, which hung trembling in the balance!

My presentiments were more than justified by the result. On Sunday (21st) the great battle of Manassas was fought, memorable in history as that of Culloden or Waterloo, which ended in the total defeat and rout of the entire 'Grand Army.'

In the world's history such a sight was never witnessed: statesmen, senators, Congress-men, generals, and officers of every grade, soldiers, teamsters - all rushing in frantic flight, as if pursued by countless demons. For miles the country was thick with ambulances, accoutrements of war, &c. The actual scene beggars all description; so I must in despair relinquish the effort to portray it.

The news of the disastrous rout of the Yankee army was cried through the streets of New York on the 22nd. The whole city seemed paralysed by fear, and I verily believe that a thousand men could have

Page 18

marched from the Central Park to the Battery without resistance, for their depression now was commensurate with the wild exultation of a few days before.

On the afternoon of that day I left New York for Washington, where I arrived at six o'clock in the morning of the 23rd, in a most impatient mood. Even at that early hour friends were awaiting my arrival, anxious to recount the particulars of the glorious victory. A despatch was also received from Manassas by me - 'Our President and our General direct me to thank you. We rely upon you for further information. The Confederacy owes you a debt. (Signed) JORDON, Adjutant-General.' My first impulse was to throw myself upon my knees and offer up my tearful thanks to the Father of Mercy for his signal protection in our hour of peril.

During my journey from New York the craven fear of the Yankees was manifested everywhere. At Philadelphia most of the women got off. I was advised to do so by Lieutenant Wise, of U. S. A. (son-in-law of Edward Everitt), as he said, 'It was believed that the rebels of Baltimore would rise, in consequence of the rout of the Federal army.' I laughingly replied, 'I have no fears; these rebels are of my faith. Besides, I fear, even now, I shall not be in time to welcome our President, Mr. Davis, and the

Page 19

glorious Beauregard.' He sneeringly replied, 'that I should probably see those gentlemen there in irons.' I received a scowl also from Mr. Winter Davis, who was a passenger from New York, and had been loud- mouthed and denunciatory against the South during the journey. I observed, however, that he and Lieutenant Wise got off at Philadelphia, deeming 'discretion the better part of valour.'

A large force was distributed throughout Baltimore, and it was even difficult to thread one's way to the train on account of the military, who crowded the streets and the depôt. Thence to Washington seemed as one vast camp, and on reaching the Capitol, the very carriage-way was blocked up by its panic-stricken defenders, who started at the clank of their own muskets. After a hurried toilette and breakfast I went up to the U. S. Senate, where I saw the crest-fallen leaders who, but a few days before, had vowed 'death and damnation' to our race. Several crowded round me, and I could not help saying that, if they had not 'good blood,' they had certainly 'good bottom,' for they ran remarkably well.

For days after the wildest disorder reigned in the Capitol. The streets were filled with straggling soldiers, each telling the doleful tale, and each indulging in imaginary feats of valour, which would

Page 20

throw into the shade the achievements of Coeur de Lion, Amadis de Gaul, or Jack the Giant-killer.

Even senators entered into this scramble for stray laurels, for several assured me (Wilson and Chandler) that it was their individual exertions alone which had prevented the entire 'Grand Army' from precipitating itself pell-mell into the Potomac; and they were really indebted to the discretion of a subordinate officer, that the alternative had not been forced upon them. A telegraphic order had been sent to Washington by General M'Dowell, to cut the draw of the Long Bridge, 'as Beauregard and Johnson were hotly pursuing him with fresh troops.' This bridge spanned the Potomac just opposite Washington, and was the only means of crossing the river at that point.

Crimination, and recrimination, now became the order of the day, and everybody shrank from the responsibility of the forward movement. The commanding General, Scott, said, 'I did n't do it, for I was not ready.' The Political Directory said, 'We did n't do it - it was that old dotard Scott, whom we will remove.' President Lincoln said, 'I did n't do it - by jingo, I did n't!' And so, in the end, the world was about as well informed as to who

Page 21

ordered the advance of the Grand Army as 'who killed Cock Robin.'

About this time I met Mr. Seward, who assured me That 'there was nothing serious the matter;' that I might assure my friends, upon his authority, that all would be over in sixty days. I answered him, 'Well, sir, you have enjoyed the first-fruits of the "irrepressible conflict."'

Seward had, a short time prior to his visit to England, in a speech delivered by him at Rochester, New York, as a bid for the nomination as President by the Republican party, made use of that remarkable expression of the irrepressible conflict between the white and black races, indicating, even at that early day, the policy to which he would commit himself in order to attain the object of his ambition - the Executive chair. At a later period, he endeavoured to explain this away, and in conversation with me said, 'If heaven would forgive him for stringing together two high-sounding words, he would never do it again.'

By-and-by things began to quiet down. The hirelings of the Government press exercised their ingenuity in mystifying the people. The countless hosts of the enemy were described (these, be it known, at no time exceeded twelve thousand

Page 22

actually engaged against the more than quadruple force of the invading army); their masked batteries and military defences threw into the shade the plains of Abraham, or even the fortifications of Sebastopol.

It would be idle to recount the gasconade of those who fled from imaginary foes, or to describe the forlorn condition of the returning heroes, who had gone forth to battle flushed with anticipated triumph and crowned in advance with the laurel of victory. Alas! their plight was pitiable enough. Some were described as being minus hat or shoes. Amongst this latter class was Colonel Burnside, who, on the morning that he sallied forth for The 'sacred soil,' is said to have required two orderlies to carry the flowers showered upon him by the women of Northern proclivities.

Meanwhile the muttered sound of the people's voice was heard from far and near asking meaning questions of the why and wherefore of the disasters. It was like the rumbling of the distant thunder presaging the coming storm; and well the Abolition Government knew that, if this discontent was allowed to gather strength, it would hurl them from their present lawless eminence to the ignominy they merited.

The invaders had been taught to believe that a

Page 23

bloodless victory awaited them - that the 'All hail!' of the witches of Macbeth would greet them: and so possessed were they with the idea of their philanthropic mission as liberators of an oppressed people, 'bowed under the yoke of a haughty aristocracy,' that many of their officers, particularly the famous New York 7th regiment, took far more pains to prepare white gloves and embroidered vests for 'the balls' to be given in their honour at Richmond than in securing cartridges for their muskets. When consulted on the subject I said, 'No doubt they would receive a great many balls, but I did not think that a very recherché toilet would be expected.'

The fanatical feeling was now at its height. Maddened by defeat, they sought a safe means of venting their pent-up wrath. The streets were filled with armed and unarmed ruffians; women were afraid to go singly into the streets for fear of insult; curses and blasphemy rent the air, and no one would have been surprised at any hour at a general massacre of the peaceful inhabitants. This apprehension was shared even by the better class of U. S. officers. I was urged to leave the city by more than one, and an escort offered to be furnished me if I desired; but, at whatever peril, I resolved to remain, conscious of the great service I could

Page 24

render my country, my position giving me remarkable facilities for obtaining information.

In anticipation of more fearful scenes, the inhabitants were leaving the city as rapidly as the means of transportation or conveyance could be obtained, and many even of the Federal officers sent their families to the North or other places of fancied security.

Page 25

CHAPTER III.

PANIC AT WASHINGTON.

ATTACK UPON THE PRISONERS - UNITED STATES TROOPS OBLIGED TO PROTECT THEM - MY VISIT TO THE PRISON - MR. COMMISSIONER WOOD - CHARLES SUMNER - DISMEMBERMENT OF VIRGINIA - ADMISSION OF SENATORS - REIGN OF TERROR - DETERMINATION TO REMOVE SCOTT - ELEVATION OF M'CLELLAN.

At this time a number of Confederate prisoners, who had been taken in the first day's fight when our army fell back from Bull Run, were brought to Washington, and on passing Willard's Hotel were set upon by the crowd who usually congregated there, and pelted with stones and other missiles, which seriously wounded a number. In order to prevent the prisoners from being actually torn to pieces, a company of U. S. regulars had to be called out to protect them to their quarters, the old Capitol prison; and during the march to that point the soldiers had repeatedly to threaten to fire upon the mob, who pressed upon them with shouts and obscene revilings.

Page 26

As soon as I heard of the circumstance, I went up to the prison to minister to the wants of our sufferers, and found many with severe cuts and bruises. I was accompanied by my friend Miss Mackall, and had the satisfaction of not only being the first friendly face seen by them, but to know that I had arrived at the right time; for I found there an emissary of Lincoln - I had like to have said Satan - dressed in black, with a white neckcloth, who I afterwards learned was Mr. Commissioner Wood, one of the subscribers for Mrs. Lincoln's carriage and horses, and who received his appointment in consequence thereof.

He was with great earnestness haranguing the prisoners, and trying to persuade them that they would all be hanged unless they took the oath of allegiance to the Abolition Government. I listened attentively to the man, who did not seem to relish the addition to his audience; and afterwards, as rapidly as I could, assured each group of prisoners that man's threat was idle, and only for the purpose of intimidation, and for some false announcement to the world; that the Yankees were obliged to treat them as belligerents, and hold them as prisoners of war for exchange; that our Government would fearfully retaliate any violence against them, as we held an excess of prisoners of a hundred to one. This

Page 27

satisfied them, especially the younger portion, who each refused the Yankee pardon on the terms proposed. I afterwards took the list of their various wants, and, in conjunction with high parties, whom it would be imprudent to name, supplied them with clothing and other needful things, food and beds and bedding inclusive, as the Yankees had made no provision of any kind, save the naked walls of a prison. There was an ample Confederate fund in Washington for this purpose. Mrs. Philips and family also exerted themselves in this holy work.

This lady was arrested in Washington at the same time that I was, and after a short detention was sent South. She then became a resident of New Orleans. During the reign of terror of Butler in that city a Yankee funeral passed her house, and she was seen to smile upon her balcony during the procession. For this grave offence she was dragged before him, and questioned as to her motive for doing so, to which she dauntlessly replied, 'Because I was in a good humour.' She was condemned to three months' imprisonment, upon a barren island, under a tropical sun, with soldiers' rations, and subjected to other gross and brutal indignities, until the poor lady's health gave way, and her life became imperilled. The representations and remonstrances of the medical

Page 28

attendant, who was more humane than his master, failed to procure any mitigation of the harsh sentence until the period had expired, when she was banished, an invalid for life. In the course of her examination before Butler, he said: 'I expect to be killed before I leave the South, by either you or Mrs. Greenhow;' to which she answered, 'We usually order our negroes to kill our swine!'

Mr. Charles Sumner was said to have been a complacent looker-on if not an actual participator in that chivalrous demonstration against unarmed prisoners. Mayhap his wrath was appeased by the sight of the bleeding victims, who could hold no correcting rod over his own coward shoulders.

A few days after an order was given to exclude all visitors, in which I was specially named. In spite, however, of the prohibition, I had no difficulty in communicating when I desired.

Soon after I passed into other hands my share in this good work; for more important employment occupied my time.

The Yankee Government and Yankee Congress were now exercised upon the subject of reorganising their shattered hosts. The military committee was specially charged with the task, and certainly grave efforts were being made to this end, the primary

Page 29

object being to mystify the people as to the past, in order to make them blind instruments in the future; for it was now truly a nation of subterfuges and humbugs.

At this time the solemn farce was enacted of admitting as U. S. senators the bogus members from Western Virginia. I was in the gallery of the Senate at the time, and happened to remark upon the proceedings to my own party, when a man sitting before me in the uniform of lieutenant-colonel of Yankee volunteers, in company with a number of other officers, turned and said, 'That is treason; we will show you that it must be put a stop to; we have a government to maintain,' &c. This was the first effort of the kind to repress freedom of opinion which had come under my observation, and the beginning of that reign of terror for which we should be obliged to seek precedents in the age of a Nero or Caligula. Yet I confess that it did not surprise me. I leaned forward and said deliberately, 'My remarks were addressed to my companions, and not to you; and if I did not discover by your language that you must be ignorant of all the laws of good-breeding, I should take the number of your company and report you to your commanding officer to be punished for your impertinence!' Seeing me

Page 30

addressed by him, several gentlemen came forward, as also the door-keeper, who said, 'Madam, if he insults you I will put him out.' To which I replied, 'Oh, never mind: he is too ignorant to know what he has done.' This defender of the faithful, meanwhile, played most vehemently with his sword, and I expected momentarily to have it drawn against me. His brother officers one by one withdrew, and left him alone in his glory.

A few moments after this scene a republican senator came up to the gallery to speak with me, and I related the circumstance, and advised him to go down to the Senate and move a revival of the alien and sedition law, as I supposed it would come to that, since armed ruffians were placed in the galleries to awe the crowd. This 'brave' bore it as long as possible, and finally got up and went out. I this man once more, upon the occasion of my being summoned before the U. S. commission, after I had been some eight months a prisoner. He was standing in the doorway of the building in which the commission was held, as if he expected to see me; a look of triumph lighted up his face as his eye encountered mine. I could not resist the temptation of significantly passing my finger across my throat, and saying, 'Beware!' - as Balzac's story of

Page 31

the poor Marie Antoinette and Joseph Balsamo came to my mind.

This was destined to be a day of adventure. Quite an excitement was caused by a rumour that a battle was going on across the river. The Confederate forces were at that time in possession of Arlington Heights, the former residence of the venerable Park Custus, the grandson of Washington: from him it had come by inheritance to our own great General Lee. I went with my party to the portico of the Congressional Library, whence the best view could be obtained, and saw the smoke from the camp-fires gracefully curling up, and remarked, 'That is no battle. The rebels are cooking their dinners.' A number of persons had crowded around and joined in the conversation. Some one proposed to send back to the Senate for Chandler, Wilson, and Foster, the heroic trio who had fled so valorously from the field at Manassas, spreading the news of the defeat. I objected on the score of humanity, as it was not right to give such a shock to their nervous systems, since neither of those senators had been able to stand the fire in their own pipes since that hapless Gilpin race.

Finally I fell into conversation with a lank lean man, with a big nose and a pair of green spectacles,

Page 32

who asked me if I had ever witnessed a battle. I replied that I had experienced a pronunciamento in the city of Mexico. In the course of his remarks he said that he would rather give up Washington than that it should be held by means of fortifications, but that Lincoln, Seward, and the whole set were cowards, and a great deal more which I considered useful information. I knew that this man was a senator, and fancied that it might be 'Jim Lane' of Kansas, he whom I have denominated as 'Balaam's Ass.' He said that he had seen me in the gallery of the Senate, and asked what I thought of the proceedings.

I related the attack on my liberty of speech, and wondered what sort of performance we should be treated to next, whether a tragedy or another farce; and, I confess, gave a most grotesque account of the speeches during the solemn mockery of the morning, expressing my surprise that more ingenuity had not been displayed to disguise the unconstitutionality of the act, to dismember and defraud a sovereign state of her territorial rights, individualising Trumbull's effort as one for which a schoolboy should have won a 'dunce cap.' I saw a suppressed laugh all around, and that the person to whom I spoke seemed embarrassed,

Page 33

and finally fell back and spoke with a gentleman of my party. This person came to me and said, 'Do you know that you have been talking to Senator Trumbull all this while?' I was quite as much amused at the contretemps as any of my hearers. But I should have considered it a reflection upon my good taste to have been previously cognisant of the fact, so assured Senator Trumbull that I had no idea that the subject of my criticism was the patient listener who stood before me - 'But for once in your life you have heard an honest opinion fearlessly expressed.' Abolitionist as he was, I must do him the justice to say that he behaved very well.

Humbug still continued the order of the day at Washington. Another cry was raised that the Capitol was again in danger. This time the programme was changed. The hero of Lundy's Lane and of Mexico was to be laid on the shelf, to all purposes superseded. But he still stood a mighty ruin in their way, propped by the lingering confidence of a nation, and no man was bold enough to say, 'This is not the right man for the place.' Cunning and craft were the characteristic qualities called into requisition here. Seward, with jesuitical skill, affected to support the weak old man, wishing to enact the fable of 'the monkey and the chestnuts.'

Page 34

But even his selfish policy had to yield to the tempest he had aided to raise.

As a preparation for what was to follow, Congress passed an 'act regulating the pay of the Lieutenant- General in case of his resignation' or 'voluntary retirement.'

Young America now became the theme of every tongue. The great battles of the world, both in ancient and modern times, were proved to have been fought by generals who were adolescent. Cæsar, Hannibal, and Napoleon were cited as examples, and even our own immortal Washington had many years deducted from his actual age when he fought the battles of the revolution.

The ears of the rabble were tickled by all this; justice was lost sight of; - and so a young chieftain was summoned to the field of intrigue. Nothing remarkable thus far had distinguished him above his compeers; but, touched by the magic wand of political expediency, he came forth full-fledged, with honours thick upon him. In a single day, from a subordinate position he became Major-General M'Clellan, the virtual head of the dictator's armies - whose policy of bestowing honours in advance differed widely from that of the greatest man of the present times, in the European world - Louis-Napoleon, - by whom grades were always conferred

Page 35

after the battle won, as witness Magenta, Solferino, &c. Subsequent to the rout at Manassas, President Lincoln promoted all the officers, many of whom were proved to have fled from the field in advance of their regiments.

Again comes into bold relief the sycophancy of President Lincoln's protégés. All the military qualities of any age were unscrupulously purloined, to deck the hero of the hour. By degrees they fixed upon the great Napoleon as his prototype - I suppose from the fact that he is short, and rather inclined to corpulency, as was latterly the 'Little Corporal;' and, besides, sycophants are ever ready to discern what pleases best.

Under the auspices of the 'Young General,' the military are put in motion; hither and thither they are marched, and counter-marched; mysterious movement being his forte. He, however, set himself energetically to the task of reorganising and disciplining the demoralised rabble he was called upon to command.

General Scott, who at this time was still the nominal commander-in-chief, wrote a letter to the Honourable Henry Wilson, lauding his patriotic exertion, and urging him to accept military command, and commending his capacity for such position in very high terms. By a singular coincidence, M'Clellan

Page 36

urged the same gentleman, 'to do him the honour to accept the position of chief of his staff!' This proposition was made by M'Clellan in the reception- room of President Lincoln. I mention these incidents, to show the political bias of all parties at the time; that the Abolition star was in the ascendant, and that everybody fawned upon its chosen apostles.

M'Clellan also invited the Count de Paris and Duke d'Aumale to become members of his staff. Their acceptance was heralded with great circumstance, as this infusion of the aristocratic element into the Abolition ranks was regarded as a national triumph. Edifying accounts were given of their introduction to President Lincoln, and especially to Master Bob, the Abolition scion of royalty. They were amiable ladylike-looking young Frenchmen, better fitted from their appearance to assist in Mrs. Lincoln's educational scheme (thus treading in the footsteps of their royal ancestor Louis- Philippe, who taught French in Philadelphia) than to win laurels enough to disturb the equanimity of that wise and sagacious Prince whom Providence has appointed to rule over France.

A commission of Brigadier-General was also tendered to Garibaldi.

Meanwhile the panic at Washington, instead of subsiding,

Page 37

received new impulse each day, from some extravagant rumours. A strong guard was stationed around all the public buildings. The redoubtable Jim Lane, of Kansas notoriety, and his band of ruffians, were quartered in the east room of the White House, for the protection of President Lincoln and his family. Sentinels paced to and fro in front of the house, and at six o'clock in the evening the gates were closed, and no one could enter without the countersign.

Everything about the national Capitol betokened the panic of the Administration. Preparations were made for the expected attack, and signals arranged to give the alarm. The signal was three guns from the Provost- Marshal's office, followed by the tolling of the church bells at intervals of fifteen minutes.

By a singular providence (for it would be wrong to ascribe these things to chance), I went round with the principal officer in charge of this duty, and took advantage of the situation. The alarm-guns of the Yankees were the rallying cry of a devoted band whose hearts beat high with hope. The task before them was worthy of all hazard, and our gallant Beauregard would have found himself right ably seconded by the rebels of Washington had he deemed it expedient to advance on that city.

Page 38

A part of the plan was, to have cut the telegraph wires connecting the various military positions with the War Department, to take prisoners M'Clellan and several others, thereby creating still greater confusion in the first moments of panic. Measures had also been taken to spike the guns in Fort Corcoran, Fort Ellsworth, and other important points, accurate drawings of which had been furnished to our commanding officer at Manassas by me.

Quite an ingenious plan was adopted at this time to discover if the 'rebel' communication was uninterrupted. Young Doolittle, the son of the senator of that name, and clerk of the military committee, who was an occasional and useful visitor at my house, brought me a letter for Colonel Corcoran at Richmond, with the modest request that I would send it. I told him that M'Clellan's excessive vigilance had rendered communication almost impossible, but that he might leave it and trust to the chance. He called repeatedly to ascertain whether the letter had been sent; but I understood the motive, and was always very sorry that no opportunity had occurred. I need hardly say that during this period I was in almost daily correspondence with Manassas.

The Capitol, by this, had been made one of the

Page 39

strongest fortified cities of the world - every avenue to it being guarded by works believed to be impregnable. Thirty-three fortifications surrounded it. But this alone was not deemed sufficient. Extraordinary vigilance was exercised; market-carts and news boys were overhauled, to look for treasonable correspondence - every box was either a masked battery, or infernal machine - but, alas! without success, until a sudden inspiration seized them. The Southern women of Washington are the cause of the defeat of the grand army! They are entitled to the laurels won by the brave defenders of our soil and institutions! They have told Beauregard when to strike! They, with their siren arts, have possessed themselves of the plans and schemes of the Lincoln Cabinet, and warned Jeff. Davis of them.

The most skillful detectives were summoned from far and near, to trace the steps of maids and matrons. For several weeks I had been followed, and my house watched, by those emissaries of the State Department, the detective police. This was often a subject of amusement to me; and several times, when accompanied by my young friend Miss Mackall, we would turn and follow those who we fancied were giving us an undue share of attention. Still I believed it private enterprise, originating with some philanthropist

Page 40

who had my well-being at heart; for I was slow to credit that even the fragment of a once glorious Government could give to the world such a proof of craven fear and weakness as to turn the arms, which the blind confidence of a deluded people had placed in their hands, for the achievement of other ends, against the breasts of helpless defenceless women and children. Nevertheless it is a fact, significant of events to follow. Lawless acts of violence seldom stand alone; and the careful readers of the history of the last two hundred years will find numerous parallel cases.

No nation on the face of the globe has made such rapid strides to despotism as the Federal Government. The first acts of the Republican President were to violate the express provisions of the Constitution: those safeguards provided by the wisdom of our fathers for the protection of the rights of the citizen have been suspended, under the plea of military necessity. The law of the land has given place to the law of the despot.

The first act of the Republican Congress assembled in this city of Washington on the 4th day July, 1861, was to legalise the acts of their President, thereby admitting that he, the chief magistrate the nation, had been guilty of perjury and treason

Page 41

before God and man; for his oath of office had been, to support the Constitution of the United States, and to administer the laws in accordance with its provisions. But instead of being impeached for his crimes, he was eulogised, and unlimited powers were conferred upon him.

A few voices were raised in protest in both houses of Congress. Breckenridge made a speech on the occasion which must transmit his name with undying honour to posterity; for it was the last cry of freedom ever to be heard in those walls, until they shall have been purged by fire and blood.

No voice of inspiration is needed to point where this nation is drifting. The crimes which have disgraced other lands, from the contemplation of which humanity shrinks appalled, will yet be enacted here. A people do not sink at once from the height of prosperity, and power, and civilisation, to the lowest abyss of lawless despotism, without some spasmodic attempts at counteraction. But the systematic efforts at demoralisation will soon be apparent: the public taste will become vitiated; the voice of conscience will be smothered by the craving for excitement; fanaticism will assume the guise of patriotism, and under that sacred name the rights of civilisation will be trampled under foot.

Page 42

The guillotine was a most humane invention; but in the hands of a lawless mob became a fearful instrument of vengeance, and has damned to immortality its harmless inventor, who also perished by it. Mr. Lincoln and his Minister of State, Mr. Seward, have set at work the social guillotine; and I am but a poor prophet unless, in its evolutions, they also become the victims; for they have inaugurated a mighty revolution, the bitter fruits of which will be brought home to them.

It was the intention of the Abolitionists to arrest Breckenridge for treason immediately on the conclusion of his speech, had he afforded the slightest pretext for doing so. Several of the prominent leaders had told me, 'that they had committed a blunder in ever having allowed him to take his seat.' I warned Mr. Breckenridge of his danger, and gave him the names of the parties who had spoken thus to me. He at once recognised his peril, and re-worded his speech as to avoid the threatened danger, at which the Abolitionists were greatly chagrined.

Charles Sumner was anxious that a test-oath should be applied to those senators who were considered of doubtful loyalty to the Lincolnites, as had be already done to officers of the army; Colonel John

Page 43

Lee having the unenviable notoriety of being the first Southern-born officer who subscribed to this oath of allegiance to the tyrant.

It must not be supposed that the social element was neglected in these times of stern alarm. Mr. Seward was too new in his character of diplomatist to disregard so important a concomitant of success. He had recently returned from Europe - had basked in the smiles of Lord John Russell and the Exeter Hall clique - and had been taught by a charming diplomatic lady that a white neck-cloth was alone comme il faut at a dinner or evening party. So he took the Club House, made memorable in Washington on account of its proximity to the scene of that fearful Sickels tragedy, and commenced a series of entertainments, which were attended by a vast crowd of men in uniforms, and a sparse sprinkling of women, who, with few exceptions, were not of a class to shed much lustre on the Republican Court; for the refinement and grace which had once constituted the charm of Washington life had long since departed, and, like its former freedom, was now, alas! a tradition only.

We find, by historical observation, that nations as they begin to decline in morality and civilisation have always a morbid passion for pastimes and amusements

Page 44

which address themselves to the physical senses. France, in her days of revolution, had her saturnalia to the Goddess of Liberty - Mexico her bull-fights - the Yankee nation her colossal reviews and mimic battles, at which President Lincoln, surrounded by his satellites, complacently assisted, as if the salvoes of artillery which rent the air in his honour could shut out from the ears of Heaven, as well as from his own, the wail of the widow and the orphan.

It is difficult to reconcile the frivolity of these people from the beginning with a sense of the perils which environed them. Mr. Seward, even after the direful rout at Manassas - when hecatombs of their dead lay manuring the sacred soil - persisted in saying, 'There is nothing the matter!' President Lincoln still said, 'There is nobody hurt!' even though he had reached the Capitol like an escaped convict, under the disguise of a 'Scotch cap and cloak,' and continued for days to edify his visitors with an account of his ingenuity in eluding the supposed murderous snare which had been set for him - leaving his wife and children, however, with true Yankee chivalry, to encounter the dreadful fate from which he so exultantly described himself as having escaped.

'Nobody hurt!' and yet this same unconstitutional

Page 45

President pursues his evening drive under escort of an armed guard, which quite takes us back to the feudal ages. The sight pleased me, I confess, as a foreshadowing of the gathering tempest.

I wish I could present to the mind's eye a picture of Washington as it really appeared under the desecration of the Black Republican rule. Those of its former population who remained from necessity or other causes had disappeared entirely from the surface of society. A new people had taken their places, as distinct and marked in their characteristics as any barbarian race that ever overran Christendom, and who, in their insolent pride of conquest, speedily effaced every landmark of civilisation.

The city was filled to overflowing with greedy adventurers seeking office. Day after day, and month after month, the resistless tide, with black glazed carpet-bag in hand, came rolling in. I sometimes thought them the lost tribes of Israel, who, sniffing from afar the golden harvest, had pierced the confines of eternity and found their way over. Every thoroughfare - every public building - doorway, and corridor, and steps - were blocked up by these sturdy beggars, who came to demand the spoils of victory; and who, disdaining the accommodation of hotel or lodging-house, ate their meals out of those same black

Page 46

glazed carpet-bags, on the highways or byways, and slept like dogs in a kennel.

Add to all this the thousands of drunken demoralised soldiers who filled the streets, crowding women into the gutters, with ribald and obscene observations, and sometimes with more personal insult. It was even difficult to look from the windows without the sense of decency being shocked; and the public squares, which were once such favourite resorts, had now become the chosen places of debauchery and crime. The schools throughout the city had been closed, as it was no longer safe for children to go into the street.

Upon no class of the community did this total abnegation of all the laws, both human and divine, tell with such saddening effect as upon the free coloured population, especially the women, whose sober industrious habits of former days had given place, under the influence of the new order of things, to the most unbridled licentiousness, and who were to be seen at all public places bedecked in gorgeous attire, sharing the smiles of the volunteer officers and soldiers with the republican dames and demoiselles.

I have frequently received the answer, when I have sent to demand the services of a negro serving-woman, 'that she would not come, for the reason

Page 47

that she had an engagement to drive or walk with a Yankee officer.'

I will gladly turn from the contemplation of this heart-sickening picture to the comedy of 'High Life below Stairs' being enacted at the White House. Mrs. Lincoln, disregarding, or more probably being ignorant of, the conventional usages which have from time immemorial regulated the etiquette at the Presidential mansion, created much amusement and ridiculous comment upon the first public occasion after the assumption of her new dignity in the reception of the ladies of the diplomatic corps.

The custom at Washington is precisely similar to that practiced at all other courts, that, as soon after the installation of a new chief as is practicable, the representatives of foreign nations accredited to the Government should be formally introduced by the Secretary of State, and a complimentary address delivered in their behalf by the doyen, or oldest member of the diplomatic body, which is answered by the President - all being arranged beforehand, even to the exchange of the addresses.

In like manner the ladies of the diplomatic corps, after due notification, are presented to the feminine representative of the White House.

This ceremony is always regarded as one of

Page 48

importance, second only to a presentation at St James's or St. Cloud. The ladies in question, after due notification, presented themselves en grande tenue at the White House, where they were ushered very unceremoniously into one of the reception-rooms, and left in a most uncomfortable state of uncertainty as to the next step in the programme. After some time, and when speculation had well nigh exhausted itself, a young woman, dressed in a pink wrapper and tucked petticoat, came bounding in, not making, however, the slightest recognition of the presence of the distinguished visitors assembled, but stood balancing herself first on one foot and then the other, surveying them meanwhile with a most nonchalant air, and after having gratified her curiosity withdrew with as little ceremony as she had entered.

The surprised enquiry of the stranger ladies, 'Is this Mrs. Lincoln?' had scarcely subsided, when a small dowdy-looking woman, with artificial flowers in her hair, appeared. The first idea was that she was a servant sent to make excuses for the singular delay of Mrs. Lincoln. But she approached and addressed herself in conversation to the wife of a secretary of legation, and it gradually dawned upon the part that this was the feminine representative of the Black Republican Royalty, and they made the best of the

Page 49

awkward situation. Mrs. Lincoln herself, however, not seeming to be aware that everything was not conducted in the most orthodox fashion, had instructed a little lady to inform Mme. Mercier that she was studying French, and would by winter be able to converse with her in that language. By this she has probably discovered that there is no 'royal road to learning.'

I had a most graphic description of this scene from more than one of the victims of this first Republican Court ceremony, and only wish that I could give the picture with all its nicer touches. The young lady in the tucked petticoat was a niece of Mrs. Lincoln.

Owing to the fact of Mr. Seward being master of the ceremonies, Mr. Lincoln was a little less bizarre in his ministerial reception. But at the dinner given in honour of the occasion, when the different wines were served, and he was asked which he would take, he turned to the servant with most touching simplicity and said: 'I don't know: which would you?'

This anecdote is as well authenticated as the spilling of the cup of tea on Mrs. Masham's gown.

A distinguished diplomatist, in discussing the merits of the illustrious pair, said: 'He is better than

Page 50

she, for he seems by his manner to apologise for being there.'

President Harrison is said on his death-bed to have instructed the barber who shaved him, to carry out the provisions of the Constitution; and President Lincoln, much to the chagrin of his constitutional advisers, was in the habit of discussing matters of equal importance with his servants, or 'helps,' as he termed them.

Mrs. Lincoln asserted with great energy her right to a share of the distribution of the Executive patronage. She had received as a present, from a man named Lammon, a magnificent carriage and horses, promising him in return the marshalship of the district of Columbia, one of the most lucrative offices in the gift of the Executive.

Mr. Lincoln had, however, determined to bestow the office upon another applicant, who had also paid his douceur, and who was in attendance, waiting to receive the commission which was being made out. Mrs. Lincoln came into the President's office, asked what commission it was that he was signing; and on being told, seized it from his hands, tore it in pieces, saying that she had promised it to 'Lammon,' and he should have it, else her name was not 'Mary Lincoln.'

Page 51

Lammon of course received the commission, and the discomfited applicant reported this conjugal scene; and from that hour commenced the system of votive offerings at the shrine of Mrs. Lincoln.

It had been a custom at Washington to distribute the hay and grass, cut from the public grounds, to the poor and meritorious population of the city. It was a cheap and graceful charity on the part of the Government, duly appreciated by the recipients; for, thus aided, many a poor widow was enabled to buy bread for her children, from the proceeds of milk from her cow. Mrs. Lincoln put a stop to this praiseworthy custom, and claimed it as one of her perquisites.

Commonplace and vulgar as these incidents may seem, they are, however, useful illustrations of the practical application of William M. Marcy's famous aphorism, 'To the victors belong the spoils.' The anecdotes of Queen Christina of Sweden present more clearly the character and degree of civilisation of the people over whom she reigned than any laboured historical effort could have done; and no one would dream of describing a royal banquet amongst the Fejee islanders and omit the cold bishop on the side-table.

Page 52

CHAPTER IV.

DAYS OF TRIAL.