NARRATIVE OF PRISON LIFE

AT BALTIMORE AND JOHNSON'S ISLAND, OHIO:

Electronic Edition.

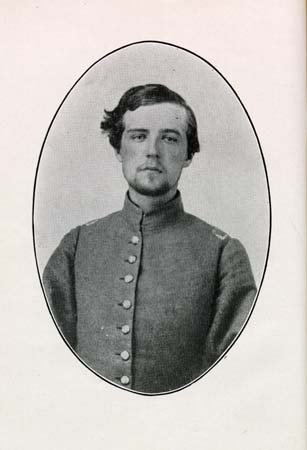

Shepherd, Henry E. (Elliot), M. A., LL. D., 1844-1929

Funding from the Library of

Congress/Ameritech National Digital Library

Competition

supported the electronic publication of this

title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Tricia Walker

Images scanned by

Tricia Walker

Text encoded by

Jill Kuhn and Natalia Smith

First edition, 1998

ca. 70K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

1998.

Call number E616 .J7 S5 1917 (Davis Library, UNC-CH)

The electronic edition

is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American

South,

Beginnings to 1920.

Library of Congress Subject Headings,

21st edition, 1998

Any hyphens occurring

in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks

and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and

left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and

left quotation marks are encoded as ' and '

respectively.

Indentation in lines

has not been preserved.

Running titles have

not been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text using Author/Editor

(SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

LC Subject Headings:

- Shepherd, Henry E. (Henry Elliot), 1844-1929.

- Prisoners of war -- United States -- Biography.

- Prisoners of war -- Maryland -- Baltimore -- Biography.

- Prisoners of war -- North Carolina -- Biography.

- Johnson Island Prison.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Prisoners and prisons.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Hospitals.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Personal narratives, Confederate.

- 1998-12-18,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

1998-11-20,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

1998-11-12,

Jill Kuhn

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 1998-09-22,

Tricia Walker

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

NARRATIVE OF PRISON LIFE

AT BALTIMORE AND JOHNSON'S

ISLAND, OHIO

BY

HENRY E. SHEPHERD, M. A., LL. D.

Formerly Superintendent of Public Instruction, Baltimore.

Author of "The Life of Robert E. Lee," "History of

the English Language," "Commentary upon

Tennyson's 'In Memoriam,' " etc.

1917

Commercial Ptg. & Sta. Co.

Baltimore

Page 5

NARRATIVE OF PRISON LIFE

I WAS captured at Gettysburg on the fifth day of July, 1863. A bullet had passed through my right knee during the fierce engagement on Culp's Hill, July 3rd, and I fell into the hands of the Federal Army.

By the 6th of July Lee had withdrawn from Pennsylvania, and, despite the serious nature of my wound, I was removed to the general hospital, Frederick City, Md. Here for, at least a month, I was under the charge of the regular army surgeons, at whose hands I received excellent and skillful treatment. For this I have ever been grateful. I recall, also, many kindnesses shown me by a number of Catholic Sisters of Frederick, whose special duty was the care of the sick and the wounded.

On the 14th of August I was taken to Baltimore. Upon arriving, I was forced to march with a number of fellow prisoners from Camden Station to the office of the Provost Marshal, then situated at the Gilmor House, directly facing the Battle Monument. The weather was intensely hot, and my limb was bleeding

Page 6

from the still unhealed wound. After an exhausting delay, I was finally removed in an ambulance to the "West Hospital" at the end of Concord street, looking out upon Union Dock and the wharves at that time occupied by the Old Bay Line or Baltimore Steam Packet Company.

The West Building was originally a warehouse intended for the storage of cotton, now transformed into a hospital by the Federal government. It had not a single element of adaptation for the purpose to which it was applied.

The immense structure was dark, gloomy, without adequate ventilation, devoid of sanitary of hygienic appliances or conveniences, and pervaded at all times by the pestilential exhalations which arose from the neighboring docks. During the seven weeks of my sojourn here, I rarely tasted a glass of cold water, but drank, in the broiling heat of the dog days, the warm, impure draught that flowed from the hydrant adjoining the ward in which I lay. My food was mush and molasses with hard bread, served three times a day.

When I reached the West Building, I was almost destitute of clothing, for such as I had worn was nearly reduced to fragments, the surgeons having multilated it seriously while treating my wound received at Gettysburg.

Page 7

My friends made every effort to furnish me with a fresh supply but without avail. The articles of wearing apparel designed for me were appropriated by the authorities in charge, and the letter which accompanied them was taken unread from my hands. Moreover, my friends and relatives, of whom I had not a few in Baltimore, were rigorously denied all access to me; if they endeavored to communicate with me, their letters were intercepted; and if they strove to minister to my relief in any form, their supplies were turned back at the gate of the hospital, or confiscated to the use of the wardens and nurses.

On one occasion a party of Baltimore ladies who were anxious to contribute to the well being of the Confederate prisoners in the West Building, were driven from the sidewalk by a volley of decayed eggs hurled at them by the hospital guards. I was present when this incident occurred, and hearing the uproar, limped from my bunk to the window, just in time to see the group of ladies assailed by the eggs retreating up Concord street in order to escape these missiles. They were soon out of range, and their visit to the hospital was never repeated, at least during my sojourn within its walls.

I remained in West Hospital until September

Page 8

29th, 1863, at which date I was transferred to Johnson's Island, Ohio, our route being by the Northern Central Railway from Calvert Station through Pittsburg to Sandusky, Ohio. Our party consisted of about thirty-five Confederate officers, one of the number being General Isaac R. Trimble, the foremost soldier of Maryland in the Confederate service, who was in a state of almost absolute helplessness, a limb having been amputated above the knee in consequence of a wound received at Gettysburg on the 2nd of July.

A word in reference to the methods of treatment, medical and surgical, which prevailed in West Hospital, may serve to illustrate the immense advance in those spheres of science, since the period I have in contemplation - 1863-64. Lister had only recentlv promulgated his beneficent and far reaching discovery, aseptics; and even the use of anaesthetics, which had been known to the world for nearly fifteen years, was awkward, crude and imperfect. The surgeons of that time seemed to be timorous in the application of their own agency, and the carnival of horrors which was revealed on more than one occasion in the operating room, might have engaged the loftiest power of tragic portrayal displayed by the author of "The Inferno." The gangrene was cut from my wound, as a butcher

Page 9

would cut a chop or a steak in the Lexington market; it may have been providential that I was delivered from the anaesthetic blundering then in vogue, and "recovered in spite of my physician." Consideration originating in sensibility, or even in humanity, found no place in West Hospital. To illustrate concretely, a soldier, severely wounded, was brought into the overcrowded ward in which I lay. There was no bunk or resting place at his disposal, but one of the stewards recognizing the exigency, soon found a ghastly remedy. "Why," he said, pointing to a dying man in his cot, "that old fellow over there will soon be dead and as soon as he is gone, we'll put this man in his bed." And so the living soldier was at once consigned to the uncleansed berth of his predecessor. Five years after the war had passed into history, I met the physician who had attended me, on a street car in South Baltimore. He did not recognize me, as I had been transformed from boyhood to manhood, since I endured my seven weeks' torture from thirst and hunger in the cavernous recesses of West Hospital. Among the notable characters who visited the sick and wounded, was Thomas Swann, associated in more than one relation with the political fortunes of Maryland. The object of his mission was to prevail upon his nephew, then in the Confederate service, to forswear himself and become

Page 10

a recreant to the cause of the South. His purpose was accomplished without apparent difficulty, or delay in assuring the contemplated result. Rev. Dr. Backus, pastor of the First Presbyterian Church, was another visitor whom I recall. Not one of those who would gladly have ministered to my needs, was ever allowed to cross the threshold, or in any form to communicate with me.

The first of October, 1863, found me established in Block No. 11, at Johnson's Island, Ohio. This, one of the most celebrated of the Federal prisons, is situated about three miles from Sandusky, near the mouth of its harbor, not remote from the point at which Commodore Perry won his famous victory during the second war with England, September 10th, 1813. On every side, Lake Erie and the harbor encompassed it effectually. Nature had made it an ideal prison. There was but a single hope of escape, and that was by means of the dense ice which enveloped the island during the greater part of the winter season. I once saw 1,500 Federal soldiers march in perfect security from Sandusky to Johnson's Island, a distance of three miles, across the firmly frozen harbor. This was in January, 1864. The area of the island was estimated at eight acres; it is now devoted to the peaceful purpose of grape culture.

During the summer months, when the lake

Page 11

was free from ice, a sloop of war lay constantly off the Island, with her guns trained upon the barracks. Yet, notwithstanding the seemingly hopeless nature of the surroundings, there were a few successful attempts to escape. I knew personally at least two of those who scaled the high wall and made their way across the frozen harbor under cover of the friendly darkness. One of these, Colonel Winston, of Daniel's N. C. Brigade, during the fearful cold January, 1864, covered his hands with pepper, and wearing a pair of thick gloves, sprang over the wall, escaped to Canada, and reached the Confederacy via Nassau and Wilmington, N. C., running the blockade at the latter point. Another was Mr. S. Cremmin, of Louisiana, for many years principal of a male grammar school in Baltimore, who died as recently as 1908. Mr. Cremmin reached the South through Kentucky, cleverly representing himself as an ardent Union sympathizer. Those who failed, as by far the greater number did (for I can recall not more than three or four successful attempts in all), were subjected to the most degrading punishments in the form of servile labor, scarcely adapted to the status of convicts.

This island prison was intended for the confinement of Confederate officers only, of whom there were nearly three thousand immured within

Page 12

its walls during the period of my residence. The greater part of these had been captured at Gettysburg and Port Hudson, just at the date of the suspension of the cartel of exchanges of prisoners on the part of the Federal government, July, 1863.

As it is the aim of this narrative to present a simple statement of personal experiences, not impressions or inferences deduced from the narrative of others, every incident or episode described is founded upon the individual or immediate knowledge of the writer. I relate what I saw and heard, not what I received upon testimony, however accurate or trustworthy. My record of the period that I passed at Johnson's Island will be devoted to the consideration of several essential points, each of them being illustrated by one or more specific examples. To state them in the simplest form, they are: The rations served to the Confederate prisoners; measures used to protect them from the extreme rigor of the climate as to fuel and clothing; their communication with their friends in the South, by means of the mails conveyed through the medium of the flag of truce boats, via Richmond and Aiken's Landing; and the treatment accorded them in sickness by the physicians in charge of the hospital. These, I believe, include the vital features involved in a narrative of my experiences as a prisoner in Federal

Page 13

hands.

During the earlier months of my life on the Island, a sutler's shop afforded extra supplies for those who were fortunate enough to have control of small amounts of United States currency, This happier element, however, included but a limited proportion of the three thousand, so that, for the greater part, relentless and gnawing hunger was the chronic and normal state. But even this merciful tempering of the wind to the shorn lambs of implacable appetite, was destined soon to become a mere memory; for suddenly and without warning, the sutler and his mitigating supplies passed away upon the ground of retaliation for alleged cruelties inflicted upon Federal prisoners in the hands of the Confederate government. Then began the grim and remorseless struggle with starvation until I was released on parole and sent South by way of Old Point during the final stages of the siege of the Confederate capital.

With the disappearance of the sutler's stores and the exclusion of every form of food provided by friends in the North or at the South, there came the period of supreme suffering by all alike. Boxes sent prisoners were seized, and their contents appropriated. Thus began, and for six months continued, a fierce and unresting conflict to maintain life upon the minimum of rations furnished

Page 14

from day to day by the Federal commissariat. To subsist upon this or to die of gradual starvation, was the inevitable alternative. To illustrate the extreme lengths to which the exclusion of supplies other than the official rations was carried, an uncle of mine in North Carolina, who represented the highest type of the antebellum Southern planter, forwarded to me, by flag of truce, a box of his finest hams, renowned through all the land for their sweetness and excellence of flavor. The contents were appropriated by the commandant of the Island, and the empty box carefully delivered to me at my quarters. The rations upon which life was maintained for the latter months of my imprisonment were distributed every day at noon, and were as follows: To each prisoner one-half loaf of hard bread, and a piece of salt pork, in size not sufficient for an ordinary meal. In taste the latter was almost nauseating, but it was devoured because there was no choice other than to eat it, or endure the tortures of prolonged starvation. Stimulants such as tea and coffee were rigidly interdicted. For months I did not taste either, not even on the memorable first of January, 1864, when the thermometer fell to 22 degrees below zero, and my feet were frozen.

Vegetable food was almost unknown, and as a natural result, death from such diseases as

Page 15

scurvy, carried more than one Confederate to a grave in the island cemetery just outside the prison walls. I never shall forget the sense of gratitude with which I secured, by some lucky chance, a raw turnip, and in an advanced stage of physical exhaustion, eagerly devoured it, as I supported myself by holding on to the steps of my barrack. No language of which I am capable is adequate to portray the agonies of immitigable hunger. The rations which were distributed at noon each day, were expected to sustain life untill the noon of the day following. During this interval, many of us became so crazed by hunger that the prescribed allowance of pork and bread was devoured ravenously as soon as received. Then followed an unbroken fast until the noon of the day succeeding. For six or seven months I subsisted upon one meal in 24 hours, and that was composed of food so coarse and unpalatable as to appeal only to a stomach which was eating out its own life. So terrible at times were the pangs of appetite, that some of the prisoners who were fortunate enough to secure the kindly services of a rat-terrier, were glad to appropriate the animals which were thus captured, cooking and eating them to allay the fierce agony of unabating hunger. Although I frequently saw the rats pursued and caught, I never tasted their flesh when cooked, for I was so painfully affected by nausea,

Page 16

as to be rendered incapable of retaining the ordinary prison fare.

I had become so weakened by months of torture from starvation that when I slept I dreamed of luxurious banquets, while the saliva poured from my lips in a continuous flow, until my soldier shirt was saturated with the copious discharge.

The winters in the latitude of Johnson's Island were doubly severe to men born and raised in the Southern States. Moreover, the prisoners possessed neither clothing nor blankets intended for such weather as we experienced. During the winter of 1863-64, I was confined in one room with seventy other Confederates. The building was not ceiled, but simply weather-boarded. It afforded most inadequate protection against the cold or snow, which at times beat in upon my bunk with pitiless severity. The room was provided with one antiquated stove to preserve 70 men from intense suffering when the thermometer stood at fifteen and twenty degrees below zero. The fuel given us was frequently insufficient, and in our desperation, we burned every available chair or box, and even parts of our bunks found their way into the stove. During this time of horrors, some of us maintained life by forming a circle and dancing with the energy of dispair.

The sick and wounded in the prison hospital

Page 17

had no especial provision made for their comfort. They received the prescribed rations, and were cared for in their helplessness, as in their dying hours, by other prisoners detailed as nurses To this duty I was once assigned and ministered to my comrades as faithfully as I was able from the standpoint of youth and lack of training.

The mails from the South were received only at long and agonizing intervals. I did not hear a word from my home until at least four months after my capture. The official regulations prescribed 28 lines as the extreme limit allowed for a letter forwarded to prisoners of war. When some loving and devoted wife or mother exceeded this limit, the letter was retained by the commandant, and the empty envelope, marked "from your wife," "your mother," or "your child," was placed in the hands of the prisoner. During my confinement at Johnson's Island, I succeeded in communicating with ex-President Pierce, whom my uncle, James C. Dobbin, of North Carolina, had prominently supported in the political convention which nominated Mr. Pierce at Baltimore in 1852. Knowing this fact, and that my uncle had been closely associated with Mr. Pierce as Secretary of the Navy, I addressed a letter to the former President, in the hope that he might exert some salutary influence which would induce the authorities to ameliorate our unhappy condition.

Page 18

I received a most kind and cordial letter from Mr. Pierce, who declared "You could not entertain a more mistaken opinion than to suppose that I have the slightest power for good with this government."

Among the Confederate officers who were imprisoned at Johnson's Island at different times and during varying periods, were a number who in latter years won fame and fortune in their respective spheres, material or intellectual, professional or commercial. Many of these I knew personally, and I insert at this point the names of some with whom I came into immediate relation. In this goodly company I recall General Archer, of Maryland; General Edward Johnson, of Virginia; General Jeff. Thompson, of the Western Army; Col. Thomas S. Kenan, of North Carolina; General Isaac R. Trimble, of Maryland; Col. Robert Bingham, the head of the famous Bingham School of North Carolina; General James R. Herbert, of Baltimore; Col. Henry Kyd Douglas, of Jackson's staff; Col. K. M. Murchison, of North Carolina; Col. J. Wharton Green, owner of the famous Tokay Vineyard, near Fayetteville, North Carolina; William Morton Brown, of Virginia, Rockbridge Artillery; Captain B. R. Smith, of North Carolina; Captain Joseph J. Davis, of North Carolina; Lieutenant Adolphus Cook, of Maryland; Lieutenant Houston, of

Page 19

Pickett's Division; Captain Ravenel Macbeth, of South Carolina; Captain Matt. Manly of North Carolina; Lieut. Bartlett Spann, Alabama; Lieut. D. U. Barziza, of Texas; (Lieutenant Barziza was named "Decimus et Ultimus," as the "tenth and last" of the Barziza children); Lieutenant McKnew, of Maryland; Lieutenant Crown, of Maryland; Lieut. A. McFadgen, of North Carolina; Lieutenant McNulty, of Baltimore; Lieutenants James Metz, Moore, George Whiting, Nat. Smith, of North Carolina; Major Mayo, Captain Hicks, Captain J. G. Kenan, of North Carolina; Captain Peeler, of Florida; Colonel Scales, of Mississippi; Colonel Rankin, Colonel Goodwin, Lieutenant-Colonel Ellis, Lieutenant-Colonel "Ham" Jones, all of North Carolina; Captain J. W. Grabill, of Virginia; Captain Foster, of Mosby's Command; Dr. Fabius Haywood and Lieutenant Bond, from North Carolina; Colonel Lock and Colonel Steadman, of Alabama; Captain Foster, Captain Gillam, Adjutant Powell, of North Carolina; Lieutenants King and Jackson, of Georgia.

Many of these whom I have named, are still living, and this list may be indefinitely extended. They will attest the essential accuracy of every statement that this narrative contains.

A monument designed by Sir Moses Ezekiel, himself a Confederate veteran, and a former

Page 20

cadet at the school of Stonewall Jackson, was dedicated in 1908 to the memory of the Confederate officers whose final resting place is near this island prison by Lake Erie.

I regret that a rational regard for the conditions of space renders impracticable a more elaborate narrative of my life as a captive on the narrow island which lies at the mouth of the Bay of Sandusky. A mere enumeration of those with whom I was brought into contact, representing every Southern State from Maryland to Texas, the Ogdens, Bonds, Kings, Manlys, Jacksons, Lewises, Mitchells, Jenkines, Allens, Winsors, Crawfords, Bledsoes, Beltons, Fites, in addition to those already named, forms a mighty cloud of witnesses, a line stretching out almost to "the crack of doom." A melancholy irony of fate marked a large element of the very limited company who escaped by their own daring, who were so fortunate as to secure release by exchange, or by the influence or intercession of friends in accord with the Federal government. I recall among these, Colonel Boyd, Colonel Godwin, Captain George Byran, who fell in the forefront of the fray, charging a battery near Richmond (1864), dying only a few moments ere it passed into our hands; and Colonel Brable who, at Spottsylvania, refused to surrender, and accepted death as an alternative to be preferred to a renewal of

Page 21

the tortures involved in captivity. While life on the island implied gradual starvation of the body as an inevitable result of the methods which prevailed, I found food for the intellect in devotion to the books which had been supplied to me by loving and gracious friends whose home was in Delaware. There was no lack of cultured gentlemen in our community, and in their goodly fellowship I applied my decaying energies to the Latin classics, Blackstone's Commentaries, Macaulay's Essays; and found my recreation in Victor Hugo, whose "Les Misèrables" had all the charm of novelty, having recently issued from the press. The poet-laureate of the prison was Major McKnight, whose pseudonym, "Asa Hartz," had become a household word, not with comrades alone, but in all the States embraced within the Confederacy. I reproduce "My Love and I," written upon the island, and in my judgment, his happiest venture into the charmed sphere of the Muses.

MY LOVE AND I.

1. "My Love reposes on a rosewood frame

(A

'bunk' have I).

A

couch of feathery down fills up the same

(Mine's

straw, cut dry).

2.

"My Love her dinner takes in state,

And so do I,

The

richest viands flank her plate,

Coarse

grub have I.

Pure

wines she sips at ease her thirst to slake,

Page 22

I

pump my drink from Erie's limpid lake.

3.

"My Love has all the world at will to roam,

Three

acres I.

She

goes abroad or quiet sits at home,

So

cannot I.

Bright

angels watch around her couch at night,

A

Yank, with loaded gun keeps me in sight.

4.

"A thousand weary miles now stretch between

My

Love and I -

To

her this wintry night, cold, calm, serene,

I

waft a sigh -

And

hope, with all my earnestness of soul,

Tomorrow's

mail may bring me my parole.

5.

"There's hope ahead: We'll one day meet again,

My Love and I -

We'll

wipe away all tears of sorrow then;

Her

love-lit eye

Will

all my troubles then beguile,

And

keep this wayward Reb

from 'Johnson's Isle.' "

So a gleam from the ideal world of poesy fell upon

the gloom of the prison which Mr. Davis, in his

message to the Confederate Congress, December,

1863, described as "that chief den of horrors,

Johnson's Island."

END.