Gilbert Hunt, The City

Blacksmith:

Electronic Edition.

Barrett, Philip, 1838-1900

Funding from the National

Endowment for the Humanities

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Sarah Reuning

Text encoded by

Fiona Mills and Natalia Smith

First edition, 1999

ca. 60K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

1999.

Source Description:

(title page) Gilbert Hunt, The City Blacksmith

Philip Barrett

34 p.

Richmond

James Woodhouse & Co.

1859

Call number E444 H9 (Special Collections, The Library of Virginia)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the

American South.

This electronic

edition has been transcribed from a photocopy provided

by the Library of Virginia.

Any hyphens occurring

in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks,

em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and

left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and

left quotation marks are encoded as '

and ' respectively.

All em dashes are

encoded as

--

Indentation in lines

has not been preserved.

Running titles have

not been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text using

Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings

Language Used:

- English

LC Subject Headings:

- Slaves -- Virginia -- Biography.

- African Americans -- Virginia -- Biography.

- African American blacksmiths -- Virginia -- Biography.

- Hunt, Gilbert, 1780?-1863.

- Theaters -- Accidents -- Virginia -- Richmond.

Revision History:

- 2000-04-06,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

1999-10-28,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

1999-10-27,

Fiona Mills

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 1999-10-18,

Sarah Reuning

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

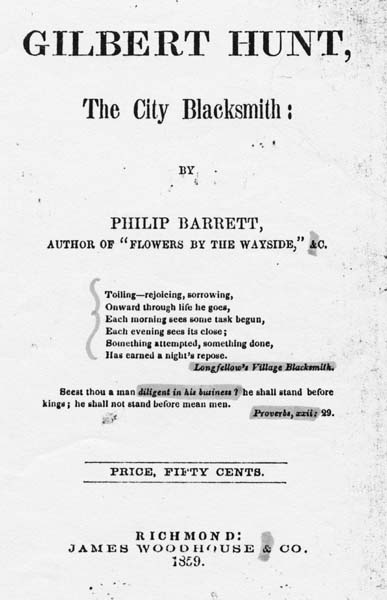

[Title Page Image]

GILBERT HUNT,

The City Blacksmith:

BY

PHILIP BARRETT,

AUTHOR OF "FLOWERS BY THE WAYSIDE," &C.

Toiling--rejoicing, sorrowing,

Onward through life he goes,

Each morning sees some task begun,

Each evening sees its close;

Something attempted, something done,

Has earned a night's repose.

Longfellow's

Village Blacksmith.

Seest thou a man diligent in his business?

he shall stand before

kings; he shall not stand before mean men.

Proverbs, xxii: 29.

PRICE, FIFTY CENTS.

RICHMOND:

JAMES WOODHOUSE & CO.

1859.

Page 3

CONTENTS.

- CHAPTER I.

HIS EARLY LIFE. - CHAPTER II.

THE BURNING OF THE PENITENTIARY. - CHAPTER III.

HIS VISIT TO AFRICA. - CHAPTER IV.

THE VISIT OF LAFAYETTE. - CHAPTER V.

THE BURNING OF THE RICHMOND THEATRE.

Page 4

GILBERT HUNT.--We stated in yesterday's issue that the citizens of Richmond would soon have their attention directed to this meritorious old negro, by an appeal to them for "material aid." He has already passed the ordinary limits of human life; "the almond tree blossoms are now adorning his brow." Towards him the hearts of our citizens should be turned with the warmest, the deepest gratitude. During three score years in humility of spirit has he lived in our midst. No man can say ought against him.--High integrity, true, generous-hearted, disinterestedness has always marked his walk and conversation.

During the war of 1812 he worked manfully, day and night, not even resting on the Sabbath day when his services were required, in preparing and mounting cannon for our defence against the encroachments of a foreign foe. At the burning of the Richmond Theatre he acted a part which attested alike his intrepidity and philanthropy, by fearlessly risking his life in behalf of some of our own citizens. Shall we neglect him in his old age, when the arm which defended, and the hand which saved our fathers and mothers are palsied with age? The same noble-hearted courage was displayed by him at the memorable burning of our Penitentiary.

We are glad to learn that a young gentleman, (the author of "Flowers by the Wayside,") known to most of our citizens, proposes publishing a brief sketch of Gilbert's life and labors--the proceeds of which are to be approriated to the aid of this magnanimous old negro. We feel assured that his effort will find a ready response in the hearts of our citizens, who have never been backward in the appreciation of whatever is true, and noble, and generous.--Richmond Whig, May 13th, 1859.

Page 5

GILBERT HUNT.

CHAPTER I.

HIS EARLY LIFE.

WITHIN the narrow limits of a small wooden tenement, on one of the most retired and unfrequented lanes of the city of Richmond, lives and labors our hero--blacksmith. For more than threescore years has he been pursuing, in our city, his humble calling. And though his head is "silver'd o'er with age," even now the merry ring of Gilbert's anvil may be heard at early dawn, saying to many a tardy young man--Be diligent in business. At his door hangs a sign painted in rude, uncouth letters. It is made of sheet iron; perhaps to save expense, perhaps to gratify the love of the old blacksmith for the metal which

Page 6

has so long yielded him a support. Here is the sign--

GILBERT HUNT,

BLACKSMITH.

We shall make him, to a great extent, his own historian:--

"I was born somewhere about the year 1780, in the county of King William, at a place called the Piping Tree, long a celebrated tavern on the Pamunkey river. My master at this time was proprietor of the tavern. He was a gentleman of considerable wealth.

At the marriage of my master's youngest daughter, I was brought to Richmond, and learned the carriage-making business under her husband, at what is now the corner of Broad and 12th streets. I was sold by my master to a gentleman, whose place of business was what is at present Broad, between 9th and 10th streets. I served him till his death--about four or five years. I was then again sold. It was during the time I was owned by my last purchaser that the war of 1812 occurred.

I remember the occurrences of that day as well as if it were yesterday. I worked eighteen

Page 7

months for the army, at my master's shop, which was situated on the corner of Locust alley and Franklin street--directly opposite the present Odd-Fellow's Hall. I ironed off carriages for the cannon, mounting one every two days. We then had four forges going constantly. I was also busily engaged in making pick-axes, &c., shoeing horses for the army, and such other work as was needed. We worked day and night, not even stopping to rest on the Sabbath day. I was also engaged in making grappling hooks for boarding the vessels down at Norfolk. During all this time, my master gave me complete control of the whole shop.

When the express came informing the people of the coming of the British, fear came upon all our citizens. My master, thinking it advisable for his family to be in the country, sent me out in search of a convenient and pleasant situation. They were then carried out of the enemy's reach. I then returned to my regular work--preparing guns for our country's defence.

During the absence of the family, my master's residence and all its contents were left entirely in my charge, and had the British come upon us, no American would have fought more

Page 8

bravely for the defence of his own home and fireside than I would have done for the defence of my master's property; for he never treated me like a servant, but rather like a member of his own household. He never spoke a cross word to, nor struck me a lick during his whole life.

When my master's family returned, I gave up to them the house and all its contents, just as they were when they were put into my hands.

I have always loved my master--I love him now."

And the noble-hearted old blacksmith stopped to wipe away a year which was stealing down his dusky cheek.

Page 9

CHAPTER II.

THE BURNING OF THE PENITENTIARY.

"THE night on which the Penitentiary was burned, I was quietly sitting down at home. It was about 10 o'clock when the alarm was first sounded. As soon as I found out where it was, I at once hurried to the place. I was then a member of the fire company. When I got there, the flames were rapidly doing their work. The wind was high, and we found it impossible to get any water. The fire then was burning furiously around the front entrance, thus shutting off all possible means of escape. I shall never forget the awfulness of the scene. It seems as plain before me, as if it had happened last night.

The prisoners were all shut up in their cells, and we still found it impossible to stop the flames. Oh! if you could have seen the poor fellows countenances, lighted up by the red light of the flames, and heard their piercing cries, you couldn't have helped doing something

Page 10

to save them, even though they were cutthroats, and rogues.

There was only one way we could get them out, that was to cut through the walls. But we couldn't get a ladder; so Captain -- , one of the bravest firemen that ever lived, got on top my shoulders, and cut a hole in the wall, through which we were able to get all of the prisoners out without any injury. We handed them down, one at a time, to the soldiers, who kept them from getting away. During all this time the flames were spreading like wild-fire over the whole building. But I was perfectly reckless; in fact, I forgot all about the fire, though the flames were hissing, and popping, and the flakes falling all around me.

I was very much struck with the conduct of the last prisoner we got out. Just as we were about pulling him out of the fire, he ran back into his cell to get his Bible. Captain -- hallooed to him, telling him he had better save himself, and let his Bible alone. But the prisoner thought differently. May-be 'twas the Bible his mother had given him when he was a boy.

The prisoners were all marched on the capitol square, and kept under guard.

Page 11

The next day I spent in making hand-cuffs for the poor fellows. I didn't think, the night before, I should have this to do."

We could but think as our humble historian narrated the last incident, how often do we find it the case, that him whom we save to-day, we must hand-cuff tomorrow. Such is life.

Page 12

CHAPTER III.

HIS VISIT TO AFRICA.

"I SAILED in the ship Harriett, Captain Johnson, from Norfolk, with one hundred and sixty souls on board. The weather was bright and cheerful, and our passage out was very pleasant, with the exception of a violent storm just before reaching the coast. A storm at sea, was something I never saw before. And when I saw the great waves rolling and pitching, and heard the wild winds moaning through the rigging, and the timbers of the vessel creaking and groaning like they were going to come to pieces every minute, I was very much frightened. But presently the winds died away, the waves became quiet and smooth again, and the bright blue sky looked as clear as if a cloud had never darkened it.

On the 17th of March we came in sight of land--the land of Africa--the land where my fathers died--the land whose soil I long had desired to tread.

On landing we went to the house of Jack

Page 13

Lewis, who had once lived in Richmond. He received us with great cordiality. I staid with him until I could make arrangements for my accommodation.

The people looked very much like those I left at home. The natives, at the colony, were almost in a state of nakedness. Two or three of the boys (natives) waited on me with a great deal of politeness. They spoke broken English quite well.

The country was as beautiful as any I ever saw, and was thickly covered with a heavy growth of trees common to that climate.

The soil I also found quite rich, and produced nearly all the grains and vegetables I had been used to at home.

During my visit to Africa, I took a trip of several hundred miles into the interior of the country. I found the people much more intelligent than I had expected. They also treated me with the greatest kindness, saying to me--'If you come from Mr. Carey's country (meaning America) you will be treated with great kindness,'

After remaining several weeks in this portion of the country, I returned to the colony.

During my trip I saw many things entirely

Page 14

new to me. There were numbers of vessels in one of the rivers getting slaves for Cuba. It made my heart sick to witness the cruelty with which they were treated. They were all securely ironed to prevent their escape, and put up in stalls and fed, like cattle, on wheat bran.

I also saw a blacksmith, sitting down on the sand, his legs crossed like a tailor's, his anvil, bellows, hammers, &c., all around him. Even in this position, he could beat me working all to pieces. I really felt ashamed of myself. After all, these Africans are not such barbarians as people make out.

After remaining several months in and about the colony, I left for home in the brig Liberia, Captain Sharp. Our voyage was very pleasant, and in November I reached Philadelphia, having been absent from America about eight months.

I was the only passenger, with the exception of one native, who was anxious to see our country. He, however, remained but a short time before returning.

I was met with great cordiality in Philadelphia, Baltimore and Richmond. Since this time I have been quietly following my calling.

I have lived in Richmond, I have labored in

Page 15

Richmond, I hope to die and be buried in Richmond."

We cannot close this chapter without adding a little anecdote, which we very much suspect lies at the bottom of our blacksmith's returning America.

"Before leaving Richmond, Captain -- presented me with a choice lot of sample tobacco, which I took out with me. I prized it very highly; so much so, that I slept with it under my head during the entire voyage. No sooner had we gotten to the coast, than a number of the natives boarded our vessel. They kissed my hands, and gave many other tokens of friendship. They looked so honest, that I never once suspected anything wrong. They spoke broken English quite well. They told me if I would give them my sample tobacco, they would land me and all my goods. This I readily consented to do. Just as soon, however, as they got my tobacco, they completely forgot my language, and I couldn't get one word out of them. They no speak English then. I paid them in advance, only to find myself completely sold by people whom I thought were perfect barbarians.

They were as wise as serpents, but not as

Page 16

harmless as doves. Our people told me afterwards they were perfect African Yankees.

After this trick, I could not help sitting down, looking towards America, taking a good cry, and saying to myself,

'Carry me back to old Virginia.' "

Page 17

CHAPTER IV.

THE VISIT OF LAFAYETTE.

"THOUGH it has been some thirty-five or forty years since Lafayette visited Richmond, yet I still remember it very well (1824). He reached here in the winter. When he landed at Rocketts, he was met by a large number of soldiers, and thousands of visitors from all parts of the state."

We throw in a little extract from the pen of an eye witness.

"Many a revolutionary soldier left the comforts of home to welcome one who had partaken of the same dangers and hardships; and mothers brought their children to see and to impress on their youthful minds the memory of the man who was beloved by Washington."

We resume our narrative--

"He came through the streets in an open carriage, drawn by four milk-white horses. The sight was really beautiful. His hat was under his arm all the way, and he was all the time bowing to the ladies who were looking out

Page 18

of the windows, and shaking their handkerchiefs towards him. The streets were crowded with people, from whom went up a continued shout of 'Welcome, Lafayette.'

He was a fine looking man, thick, well set. His hair was slightly gray. I think he was one of the humblest persons I ever saw to be so great a man. He was also very much opposed to display.

He had fought for us, and every body loved him, every body praised him. I remember myself when he passed through our country before going to Yorktown."

There are many other incidents in the life of this noble-hearted negro, which we should like to mention, but they are familiar to most of our citizens.

We cannot commence our last chapter without commending the persevering industry which enabled him at an early period in his life to purchase his freedom at a cost above eight hundred dollars.

We would also add, that for half a century has he been a consistent member of the Baptist church.

Such a man needs no praise at our hands.

Page 19

Fifty years' walk and conversation, without reproach, in the midst of any people, is certainly the highest praise which can be conferred on any one--be he rich or poor, bond or free.

Page 20

CHAPTER V.

THE BURNING OF THE RICHMOND THEATRE.

THAT which clothes the name and character of GILBERT HUNT with peculiar interest, is the noble part which he bore in the memorable burning of the Richmond Theatre, in 1811. His strong and brawny arm was the means of saving many a soul from the jaws of the devouring flames, and some of the first families in our state and city now point to him with feelings of mingled pride and gratitude for his self-sacrificing conduct on that awful night which shrouded so many happy hearts with gloom, and rendered so many joyous circles lonely and desolate.

Long may he yet live in the enjoyment of one of the most precious boons earth can afford, the remembrance of those for whom one has endangered even life itself.--May his last days be his best.

(Before giving the account of this memorial scene, as narrated almost entirely in the simple but graphic language of this magnanimous

Page 21

old negro, we deem it advisable to draw one or two extracts from other sources, feeling assured that they will be perused with interest by our readers.)

It is not often that a domestic calamity is so mortal in its character, and so widespread in its influence, as to merit a place in general history; but now one presents itself, which has formed an era in the life of Virginia, never to be forgotten. (1811.) During the winter of this year, unwonted gaiety prevailed in Richmond; brilliant assemblies followed each other in quick succession; the theatre was open and sustained by in uncommon histrionic talent; the fascinations of the season had drawn together, from every part of the state, the young, the beautiful, the gay. On Thursday night, the 26th of December, the theatre was crowded to excess. Six hundred persons had assembled within it, embracing the fashion, the wealth, and the honour of the state. A new drama was to be presented, for the benefit of Placide, a favourite actor; and it was to be followed by the pantomime of "The Bleeding Nun." The wild legend on which this spectacle was founded, had lost none of its power under the pen of Monk Lewis, and, even in pantomime, it had awakened great interests. The regular piece had been played; the pantomime had commenced; already the curtain had risen upon the

Page 22

second act, when sparks of fire were seen to fall from the scenery on the back part of the stage. A moment after, Mr. Robertson, one of the actors, ran forward, and waving his hand toward the ceiling, called aloud, "The house is on fire!" His voice carried a thrill of horror through the assembly. All rose and pressed for the doors of the building.

The spectators in the pit escaped without difficulty; the passage leading from it to the outer exit was broad, and had those in the boxes descended by the pillars, many would have been saved. Some who were thrown down by violence, were thus preserved. But the crowd from the boxes pressed into the lobbies, and it was here, among the refined and the lovely, that the scene became most appalling. The building was soon wrapped in flames; volumes of thick, black vapour penetrated every part, and produced suffocation; the fire approaching, caught those nearest to it; piercing shrieks rose above the sound of a mass of human beings struggling for life. The weak were trampled under foot, and strong men, frantic with fear, passed over the heads of all before them, in their way towards the doors or windows of the theatre.--The windows even of the upper lobby were sought; many who sprang from them perished by the fall; many were seen with garments on fire as they descended, and died soon afterwards from their wounds; few who were saved by this means escaped entirely unhurt.

Page 23

But, in the midst of terrors which roused the selfishness of human nature to its utmost strength, there were displays of love in death, which make the heart bleed with pity. Fathers were seen rushing back into the flames to save their children; mothers were calling in frenzied tones for their daughters; and were with difficulty dragged from the building; husbands and wives refused to leave each other, and met death together; even friends lost life in endeavouring to save those under their care. George Smith the Governor of Virginia, had brought with him to the theatre a young lady under his protection. Separated from her in the crowd, he had reached a place of safety, but, instantly turning back, himself and his young ward both became victims of the fire. Benjamin Butts, a lawyer of great distinction, had gained the door; but his wife was left behind. He hastened to save her, and they perished together.

Seventy persons were the martyrs of this horrible night. Besides those already named, there perished Abram Venable, the President of the Bank of Virginia, and Lieutenant Gibbon, who was destroyed in attempting to save Miss Conyers. Richmond was shrouded in mourning; hardly a family had escaped the visit of the destroying angel, and many had lost several loved ones. And the stroke was not felt only at home. It fell upon hearts far removed from the immediate scene of the disaster.

On the day succeeding this night, a father in

Page 24

Richmond, who had lost a child by the fire, wrote a letter to Matthew Clay, then a member of the House of Representatives from Virginia, to tell him that he too was called to mourn. It would be hard to imagine circumstances more affecting than those disclosed by this touching letter. The writer says, "Yesterday a beloved daughter gladdened my heart by her innocent smiles; to-day she is in heaven. God gave her to me, and God--yes, it has pleased Almighty God to take her from me. O! sir, feel for me, and not for me only; arm yourself with fortitude, while I discharge the mournful duty of telling you that you have to feel also for yourself.--Yes, for it must be told! You also were the father of an amiable daughter, now like my beloved child, gone to join her mother in heaven." "The images of both my children were before me; but I was removed by an impassable crowd, from the dear sufferers; the youngest (with gratitude to heaven I write it,) sprang toward the voice of her father, reached my assisting hand, and was extricated but; . . . my dear, dear Margaret, and your sweet Mary, with her companions, Miss Gwathmey, and Miss Gatewood, passed together, and at once, into a happier world." . . . . Oh! God! Eternity cannot banish that spectacle of horror from my recollection. Some friendly, unknown hand, dragged me from the scene of flame and death."

On the 30th December, intelligence of this

Page 25

calamity was communicated to the Senate of the United States; and, on motion of Mr. Bradley, a resolution was adopted that the senators would wear crape on the left arm for a month. On the same day, a similar resolution was adopted by the House of Representatives, having been introduced in a short and feeling address, by Mr. Dawson of Virginia.

Many years passed before the impression of this event was erased in the state where it occurred. It will never be forgotten. Some who escaped, yet survive to tell of the scene. The day after the fire, the Common Council of Richmond passed an ordinance forbidding any public show or spectacle, or any open dancing assembly for four months. A monumental church has risen on the very spot where the ill-fated theatre once stood, and its monument, bearing the names of many victims of the night, will recall to the visiter thoughts of death and of the life beyond. Yet it is not the nature of man to cherish depressing memories. Time, the great destroyer, and yet the great physician, sweeps away, first, the friends whose loss brings sorrow, and the sorrow caused by the loss.--Another theatre has been reared in the metropolis of Virginia, and another "Bleeding Nun" may yet be impersonated within its walls.

Howison's History of Va., Vol. II, Ch. VII, pp. 410-414.

Page 26

We gather the following from another source:

Temporary Theatres now again gave place to a regular one. A large brick edifice was erected in the rear of the Old Academy or Theatre Square. That, alas! was the scene of the most horrid disaster that ever overwhelmed our city, where seventy-two persons perished in the flames on the fatal 26th December, 1811, where the Monumental Church now stands, and its portico covers the tomb and ashes of most of the victims.

The writer, with some friends, reached Richmond that evening from a Christmas jaunt in the country, and went with them to the theatre, but it was so crowded that we could not obtain admission. A very few hours after, he was aroused by the cry of fire, and hastening to the spot, the first object he encountered on an open space, was a lady lying on the grass apparently in a swoon. He attempted to raise her, but she was dead. He afterwards learned that she had leaped from a window, but before she could be removed from beneath it, was crushed by those who sought for safety by following her. The next object that thrilled him was a gentleman so dreadfully excoriated that death mercifully put an end to his tortures in a few hours--but it were cruel to rehearse the many individual instances of intense suffering by the victims, and of the scarcely less intense agony of their relatives and friends.

Page 27

On the ensuing morning, the mangled, burnt and undistinguishable remains of many of the victims were taken from the ruins and interred on the spot, where their names are recorded on the monument already mentioned and the ground was consecrated to the erection of a church.

It is due to an humble but worthy man, to record the services rendered by him during the progress of this dreadful calamity. Gilbert Hunt, a negro blacksmith, possessed naturally a powerful frame, and by wielding the sledge hammer, his muscles had become almost as strong and as tough as the iron he worked.--Gilbert was aroused and besought by Mrs. Geo. Mayo, to go to the rescue of her daughter.--He was soon at the theatre. Within its walls, then filled with smoke and flame, was Dr. Jas. D. McCaw, a man who might have been chosen by a sculptor for a model of Hercules. The Doctor bad reached the window and broken out the sash, when he and Gilbert recognized each other. He called to Gilbert to stand below and catch those he dropped out. He then seized on the woman nearest to him, and lowering her from the window as far as he could reach, he let her fall. She was caught in Gilbert's arms and conveyed by others to a place of safety.--One after another the brave and indefatigable Doctor passed to his comrade below, and thus ten or twelve ladies were saved. The last one providentially was the Doctor's own sister,

Page 28

whose proportions were a feminine epitome of the Doctor himself. Gilbert caught her and broke her fall, but he says he fell with her, both unhurt.

The Doctor having rescued all within his reach, now sought to save himself. The wall was already tottering. He attempted to leap or drop from the window, but his strong leathern gaiter, an article of sportsman's apparel which he always wore, caught in a hinge or some other iron projection. and he was thus suspended in a most horrid and painful position; he fell at last, but to be lame for life. The muscles and sinews were stretched and torn and lacerated, and his back was seared by the flames, the marks of which he carried to his grave.

The Doctor directed Gilbert to drag him across the street, and place him with his back against the wall of the Baptist Church; then to get two palings from a fence oppsiote.--With these for splints and handkerchiefs for bandages, the limb was bound. Gilbert then went in search of a conveyance to carry the Doctor home. His removal from beneath the wall of the theatre had scarcely been effected, before it fell on the spot where he had fallen!

After a long period of suffering, he was able to resume practice; and his profession has been adopted by son and grandson, perpetuating the good name of Dr. McCaw, which its founder had worthily established.

Richmond in By-Gone Days, Ch. XIV, pp. 142-146.

Page 29

Our narrator begins:--

"It was on the night after Christmas, 1811. I had just returned from worship at the Baptist church and was about sitting down to my supper, when I was startled by the cry that the theatre was on fire. My wife's mistress called to me and begged me to hasten to the theatre and, if possible, save her only daughter--a young lady who had been teaching me my book every night, and one whom I loved very much. The wind was very high, and the hissing and leaping flames soon spread over the whole building. The house was built of wood, and consequently the work of destruction very short.

When I reached the building, I immediately went to the house of a colored fiddler, named Gilliat, who lived close by, and begged him to lend me a bed on which the poor frightened creatures might fall as they leaped from the windows. This he positively refused to do. I then got a step-ladder and placed it against the walls of the burning building. The door was too small to let the crowd, pushed forward by the scorching flames to get out, and numbers of them were madly leaping from the windows only to be crushed to death by the fall. I looked up and saw Dr. -- standing near one

Page 30

of the top windows and calling to me to catch the ladies as he handed them down.

I was then young and strong, and the ladies felt as light as feathers. By this means we got all the ladies out of this portion of the house. The flames, by this time, were rapidly approaching the Doctor, and beginning to take hold of his clothing; and, O me! I thought that good man who had saved so many souls was going to be burned up. He jumped from one of the windows, and when he touched the ground, I thought he was dead. He could not move an inch. No one was near him; for the wall above, was tottering like a drunken man, ready at any moment to fall and crush him to death. I heard him scream out, "Will nobody save me?" and, at the risk of my own life, I rushed to him and bore him away to a place of safety.

The scene surpassed anything I ever saw. The wild shrieks of hopeless agony, the piercing cry, 'Lord, save or I perish,' the uplifted hands, the earnest prayer for mercy, for pardon, for salvation, I think I see it now--all--all just as it happened."

And the old negro stopped to wipe away a

Page 31

tear which was trickling down his wrinkled cheek.

"The next day, I went to the scene where such awful sights had been witnessed. And oh! how my heart shudders even now at the things which then and there met my eye.--There lay, piled together, one mass of half-burned bodies--the bodies of all classes and conditions of people--the young and the old, the bond and the free, the rich and the poor, the great and the small, were all lying there together. Some of them were so badly burned that it was almost impossible to recognize them. Others were almost uninjured; yet life had left their bodies, and there they lay, cold, and stiff, and dead.

I never found my young mistress, and suppose she perished among the many other young and beautiful females, who on that dreadful night passed so unexpectedly from time to eternity.

I thought, after this, there would not be any more theatres."

The old man was silent; his tale was told, tear-drops were standing in his eyes.