The History of My Life and Work.

Autobiography by Rev. M. L. Latta, A.M., D.D.:

Electronic Edition.

Latta, M. L. (Morgan London), b. 1853

Introduction by

Rev. George Daniel, D.D.

Illustrated by The Tucker Engraving Company

Funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Lee Ann Morawski

Images scanned by

Lee Ann Morawski

Text encoded by

Chris Hill and Natalia Smith

First edition, 2000

ca. 500K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2000.

Source Description:

(title page) The History of my Life and Work.

Autobiography by Rev. M. L. Latta A.M., D.D.

(cover) History of my Life and Work.

Autobiography by Rev. M. L. Latta A.M. D.D.

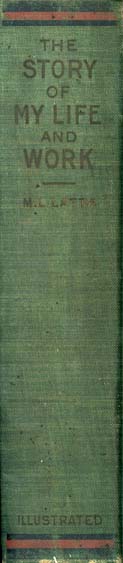

(spine) The Story of my Life and Work

Rev. M. L. Latta, A.M., D.D.

Introduction by

Rev. George Daniel, D.D.

Illustrations by

The Tucker Engraving Company

370 p., 19 ill.

Raleigh

Rev. M. L. Latta, A.M., D.D.

1903

Call number CC326.92 L36 (Cotten Collection, North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the

American South.

Any hyphens occurring

in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and

left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and

left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are

encoded as

--

Indentation in lines

has not been preserved.

Running titles have

not been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text using Author/Editor

(SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

Languages Used:

- English

LC Subject Headings:

- Latta, M. L. (Morgan London), b. 1853.

- African Americans -- North Carolina -- Raleigh -- Biography.

- African American clergy -- North Carolina -- Raleigh -- Biography.

- Slaves -- North Carolina -- Raleigh -- Biography.

- Freedmen -- North Carolina -- Raleigh -- Biography.

- African Americans -- Education.

- Latta University.

- Slavery -- North Carolina -- Raleigh -- History -- 19th century.

Revision History:

- 2000-09-01,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2000-05-16,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2000-05-15,

Chris Hill

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2000-04-17,

Lee Ann Morawski

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

[Cover Image]

[Spine Image]

REV. M. L. LATTA AND WIFE.

[1st Frontispiece Image]

CHILDREN OF REV. M. L. LATTA.

[2nd Frontispiece Image]

[Title Page Image]

[Title Page Verso Image]

THE

HISTORY OF MY LIFE

AND WORK.

AUTOBIOGRAPHY BY

REV. M. L. LATTA, A. M., D. D.

INTRODUCTION BY

REV GEORGE DANIEL, D. D.

ILLUSTRATIONS BY

THE TUCKER ENGRAVING COMPANY.

PUBLISHED BY

Rev. M. L. LATTA, A. M., D. D.

RALEIGH. MONTREAL. CHICAGO.

Page verso

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1903

BY REV. M. L. LATTA,

In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington,

D. C.

Sold only by subscription, and not to be had in book stores.

Any one

desiring a copy should address the Publisher, or in

other words write to the Institution.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Presses of Edwards & Broughton,

Raleigh, N. C.

Page 3

INTRODUCTION.

In response to the earnest request of the author of this book, I have written these introductory words.

After carefully and deliberately reading the manuscript, what I have written expresses my own opinion of the book, uninfluenced by motives of friendship for the author, or any other consideration.

The book is powerful and inspiring, full of usefulness, with broad expansion to the human mind.

In my opinion, and with my broad experience in life, there has never been a book written in the interest of the colored race better calculated to improve the condition of the public in general, and to inspire to usefulness the colored people of the South. The book is written with excellent judgment and consummate skill.

The author has produced many interesting facts, which are calculated, in my opinion, to bring the races together in one common cause, home and abroad. I have read many manuscripts, but this I have just read appeals for

Page 4

peace and justice with such force that the vilest man can not reject its pleadings. I feel safe in saying that the teaching herein involved will live and inspire its readers for centuries to come.

REV. GEORGE DANIEL, D. D.

Page 5

PREFACE

After having a broad experience as to the duty of my fellowman, I offer no apology in sending forth the history of my life and work for the edification of my readers far and near.

No one knows the difficulties and obstacles that I have passed through in preparing this volume for the consideration of the people, home and abroad. I have tried from the very depths of my heart to elucidate the seeings and unseeings that I have come in contact with during my life; God knows that I have tried from the very depths of my heart to give a clean and unblemished record. If I have erred in preparing this volume, it has been an error of the tongue, and not of the heart.

I sincerely hope that those who may read these paragraphs will be inspired with new thoughts and ideas for usefulness. Be loyal to principle be true to thy fellowmen. Press forward to the high calling, be trustworthy in all of your obligations.

It has been my highest aim from my early dawn of existence to live for the betterment of

Page 6

the people at large, and especially those that I come in contact with frequently.

Some of the history of my life and work was written in Boston, Mass., and some in Albany, N. Y. I have tried to present something to the public that would be worth of their attention. I hope something mentioned in this book will inspire them to a higher aim for usefulness, not only for themselves, but for their fellowmen.

In closing this preface, I must say a word in commending the public to the Creator of heaven and earth. If the history of my life and work is worth anything at all, it is the assistance that I have received from the Creator of heaven and earth. Let all men do their duty, but if grievances arise in the meantime, submit them to God, and God will adjust all things in the proper time.

M. L. LATTA.

RALEIGH, N. C., June 15, 1903.Page 7

CONTENTS.

- Introduction, by Rev. George Daniel, D. D . . . . . 3

- Preface . . . . . 5

- CHAPTER I.

How I Started in Life . . . . . 1 - CHAPTER II.

My Political Life . . . . . 15 - CHAPTER III.

The Colored Peoples' Theory . . . . . 19 - CHAPTER IV.

My Life in College . . . . . 24 - CHAPTER V.

Alleged Expressions Concerning the Negro Race. . . . . 35 - CHAPTER VI.

Establishment of Latta University . . . . . 36 - CHAPTER VII.

Lynchings in the Southern States . . . . . 45 - CHAPTER VIII.

Erection of the Buildings of Latta University . . . . . 49 - CHAPTER IX.

Progress of the University . . . . . 55 - CHAPTER X.

The Investigation Bureau . . . . . 59 - CHAPTER XI.

Race Distinctions . . . . . 63 - CHAPTER XII.

What I Teach my Race . . . . . 79

Page 8 - CHAPTER XIII.

Our Financial Condition . . . . . 85 - CHAPTER XIV.

Conflicting Interests . . . . . 87 - CHAPTER XV.

Relationship Between the White and Colored Races in the City of Raleigh . . . . . 92

My First Visit North in the Interest of Latta University. . . . . 97 - CHAPTER XVI.

Interview with Hon. Frederick Douglass in Boston . . . . . 101 - CHAPTER XVII.

Life in Slavery . . . . . 100 - CHAPTER XVIII.

First Investments . . . . . 131 - CHAPTER XIX.

Canvassing in the Interest of the Durham and Lynchburg Railroad . . . . . 145 - CHAPTER XX.

The Anti-Prohibition Campaign in North Carolina . . . . . 155 - CHAPTER XXI.

Scenes and Incidents During the Days of Slavery . . . . . 165 - CHAPTER XXII.

Why I Wrote this Book . . . . . 172 - CHAPTER XXIII.

A Visit to San Francisco . . . . . 181 - CHAPTER XXIV.

The Cause of the War . . . . . 193 - CHAPTER XXV.

Lynchings . . . . . 197

Page 9 - CHAPTER XXVI.

Conversation with a United States Senator . . . . . 211 - CHAPTER XXVII.

Visit to Pittsburgh, Penn.--A visit to Detroit, Mich.--In Rhode Island--In Minnesota--In Worcester, Mass.--In New York--In Connecticut . . . . . 215 - CHAPTER XXVIII.

The Presidents of the United States . . . . . 251 - CHAPTER XXIX.

Dr. A. M. Barrett . . . . . 254 - CHAPTER XXX.

In London . . . . . 269 - CHAPTER XXXI.

My Life, Building the University, Letters, Endorsements, etc. . . . . . 285 - CHAPTER XXXII.

Address before Governor's Council at Concord, New Hampshire . . . . . 333

APPENDIX.

- A Sermon by Mr. Spurgeon . . . . . 339

- Address by Mr. Spurgeon . . . . . 342

- My Experience in Farming . . . . . 352

- My Experience in Vegetable Garden . . . . . 355

- Things You Should Know . . . . . 358

- The Confidence the Railroad and Public Have in Me . . . . . 360

- Negro and Servant Problem . . . . . 361

- Mr. Casler's Solution . . . . . 364

- Supporters of the Latta University . . . . . 369

Page 10

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

- Rev. M. L. Latta and Family . . . . . Frontispiece

- Hon. Frederick Douglas . . . . . 16

- Booker T. Washington and Dr. Brooks . . . . . 24

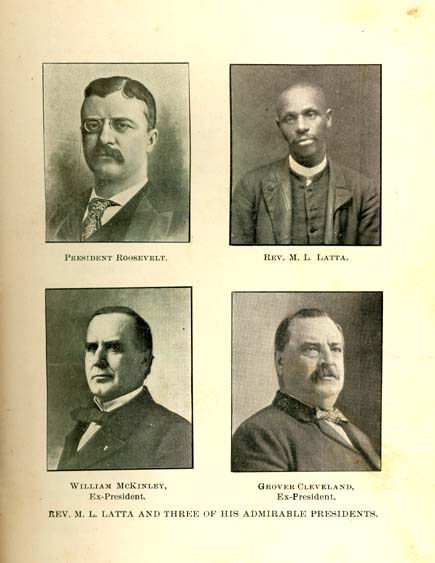

- Rev. M. L. Latta and three of his admirable Presidents, Cleveland, McKinley and Roosevelt . . . . . 32

- The House in North Carolina where Rev. M. L. Latta was born . . . . . 40

- J. H. Bivans, General Agent . . . . . 48

- D. R. Davis, former Agent for the Latta University . . . . . 48

- Rev. M. L. Latta (standing) when he first commenced building the Latta University . . . . . 72

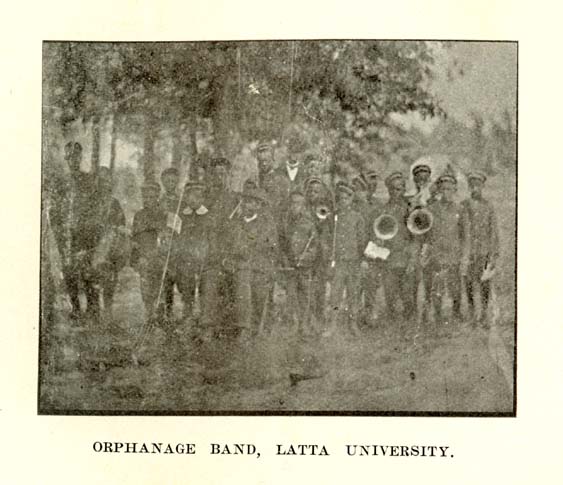

- The Orphanage Band for the Latta University . . . . . 80

- The Industrial Training Department . . . . . 104

- The Kindergarten Department . . . . . 128

- The Manual Training Department . . . . . 152

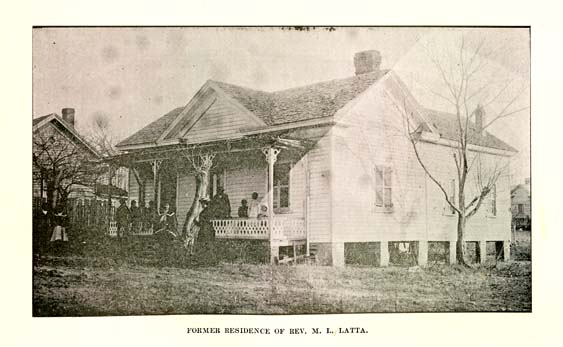

- The Former Residence of the President . . . . . 176

- Faculty and Students . . . . . 192

- Mrs. M. K. Smith, Teacher for the Latta University; Dorothy C. Funderburk, Private Secretary . . . . . 216

- Rev. M. L. Latta, making a speech at Pawtucket, R. I., at the Y. M. C. A. . . . . . 240

- The Chapel and Young Men's Dormitory . . . . . 264

- The Young Ladies' Dormitory . . . . . 288

- Rev. M, L. Latta's Present Residence . . . . . 312

- Rev. M. L. Latta making a speech at the Auditorium in London . . . . . 352

Page 11

HISTORY OF MY LIFE AND WORK.

CHAPTER I.

HOW I STARTED IN LIFE.

I was born in 1853, at Fishdam, on one of Cameron quarters, near Neuse River, about twenty-five miles from the city of Raleigh, N. C., as near as I can ascertain, as there were no records kept at that time.

I was a slave, and was only seven years old when my father died, leaving my mother and thirteen children. Soon after the war, my oldest brother was drowned, leaving the responsibility of supporting the family on my shoulders. I was hired out for several years for one dollar per month. My mother was so very poor that she was unable to send me through school. I had to work hard all day and get knots of lightwood to study my books by at night. We were not able to buy a horse, so I had to plow an ox. The only time I had to go to school was when the ground was too wet to plow.

I told my mother that I must attend some school, so I entered a free school that was near

Page 12

our home. I attended that regular one session. I attended the free school off and on for about five or six years.

I was then beginning to get along in my 'teens, and I began to take an interest in politics. I would go in public places and stand upon a box and try to make speeches. Some of the people said that I would make a great man, and a great many of them said that I would turn out to be one of the biggest fools in the world.

I had to look after my mother's family, but being a lad, I was unable to provide for them properly. I had thirteen in the family to provide for, at the age of seventeen; we suffered sometimes for the want of food. I worked many a day without sufficient food. My mother would take a bone that had been boiled, and reboil it, and make corn dumplings out of it for us to eat. Some of us cried for bread, unable to get it.

At night and morning, my mother would take the husk that came from the corn, and make coffee from it, and we had to drink the coffee that was made from the husk without any sweetening in it.

My mother thought that she would take the business out of my hands and make a change and give it to my uncle. My uncle took us and made servants out of us for his own use, and told George W. Thompson, that had Cameron's Quarters

Page 13

in charge, that we did not want to work. He said we claimed that we were not getting the proper compensation under his control.

Mother thought that she would change, and let me take the business in hand, as I had it at first. She said she had rather for us to eat bread and drink water, than to be whipped as we were.

When we could not get bread to eat for our meals, we ate parched corn.

My mother being a widow, people whipped us as they pleased. We had no father to care for us. I have cried many a day and said that God had forsaken us as a family. We worked hard, but seemed to realize very little.

I remember when I went out in the field as a slave before General Lee surrendered.

My mother would cook what little she had, and divide it among we children. I would be just as hungry when I got through eating, as I was when I commenced.

I went over to the overseer's house. I was acquainted with the cook there. I went to the door and watched her while she was setting the table. I noticed when the overseer and his family sat down to eat, I went and peeped in at the door, and I told the cook just to give me the bones and crusts. She poured them in my hat, and I ran home and divided them with the rest of the children, and she told me not to stay long, to come

Page 14

back and bring her some water. She gave me the rest of the crusts of bread, and sometimes a cup of milk, and I told mother that "The Lord has been with me to-day."

Soon after mother had taken her business out of my uncle's hands, I managed it for her several years.

When I left for college, we were so we could have a plenty to eat, and arrange things very respectably to go to church. There were two brothers older than I; the elder one got drowned. The next oldest one was born first, but people said that I was the oldest.

I saw my adopted sister and her husband put upon the block and sold. That has been about forty years ago. I have not seen them nor heard from them since.

My father and mother were both members of the church; they taught us to serve God. Experience has taught me that serving God without work does not amount to anything, and working without serving God does not amount to anything.

Page 15

CHAPTER II.

MY POLITICAL LIFE.

I began taking interest in politics. I devoted my time to politics for several years. My friends wanted me to run for the Legislature, but I refused to accept the nomination for legislator. I gave the matter my undivided attention. I soon found that there was nothing in politics for colored people. Yet at that time the Republican party, that the colored people were so closely connected with, had control of the State.

I began to prophesy as to what would be the outcome of the whole matter; yet I was not a prophet, nor the son of a prophet. I discovered through the telescope of time that the Democratic party would predominate in the future.

I advised my race (that came to me for advice) not to take any interest in politics, and if they did, to divide their votes equally between the two parties.

I, for myself, would not vote against either of the parties. I saw at that time that race prejudice had begun to accumulate and multiply, prejudice had begun to stretch its fatal wings across all of the Southern boundaries, in the hearts of the two races, extending to the Mason-Dixon line.

Page 16

Along the political lines, I might emphasize for a moment and say I do not hold either one of the races particularly responsible for this detestable outcome of the condition of the two races, but I hold both races equally responsible.

I told my race at the time that the Democratic party would control the political forces in spite of the Federal Government, because they had the money and the brains.

Numbers of them have been to me and told me that the thing came just as I said. I told them to get religion, educate themselves, buy property, stay out of politics, and put money in the bank, and as soon as we as a race handle the silver dollar, often and freely we will get recognition without any trouble, for I have said in several of my speeches, if I should see a white man in heaven, I am satisfied that he would be there chasing a silver dollar, because he loves the mighty dollar. I told them as a race, if they would get the silver dollar, the white man would chase them, regardless of color or previous condition.

It has been over twenty years ago since I have taken any interest in any political campaign. My life has been so sweet to me since I have washed my hands from politics, I pray to the God of Heaven that all thoughts would be obliterated, to inspire a single thought that had the tendency to mislead me into politics again. I

Page 16a

HON. FREDERICK DOUGLASS

Page 17

soon found out that we had nothing to interest ourselves in as a race. We are here among the predominant race. We must admit, in the first instance, that the Anglo-Saxon race owns everything in the Southern States. They own the land, they own the money, they own the railroads, and they outnumber us several times. We are but a few in number as a race. All I ask for as a member of the unfortunate race is the waste land, and ask them to give me an opportunity to build up the waste places. I admit that the colored people, as a race, are ignorant; they want to go too speedily.

Since Abraham Lincoln issued the proclamation declaring that the negro race was free, they thought that they were just as good as any one else. That much was true. For an instance, you take a man that wants a job; he goes to a man of means and asks him for a job, notwithstanding that he is not as good as the man that has means. He is submissive, in other words, he is depending on that man that has means to get a job, and if he fails to satisfy the man that he asked for the job, unless he really needs it, the man refuses to give it to him. This is the position that the colored man is placed in. We, as a race, are depending almost entirely upon the sympathetic treatment of the predominant race that we live among.

Page 18

Now, if my race will not be governed by my teaching, as I have so elaborately outlined to them as a race, the only way I see for them to do is to go back to their old original country. As Bishop Turner says, "We will have to go sooner or later and build up Africa, Egypt, Liberia, and other waste countries, formulate a government and enact laws upon the statute book that will be a credit to any nation." And let us as a race, if we go to Africa, bury ignorance, superstition, debauchery, and let the light of intelligence shine over the entire region of Africa. Let us as a race manage our legislative power with discretion, let all our actions be prudent, that other countries will spontaneously visit us and congratulate us, as to our wise management of our government affairs.

Page 19

CHAPTER III.

THE COLORED PEOPLE'S THEORY.

This history is to those that are not satisfied and want to try another country. I for myself am satisfied here. When I get dissatisfied here, I will go to Africa.

Remember, there have been many changes since 1620, when we sailed across the great Atlantic and other waters. Some of us have become red, some very yellow, and some of us almost white. Should we return to our old mother home, the sun would parch us very dark, as we were when we landed at Yorktown and other seaport towns.

Should we return, we would leave a portion of our relatives and friends here that took a part in changing our complexion.

I want the race to remember one thing, that the sun is very hot and parching in Africa. Those that want to return can do so, but I don't think that they can better their condition. For my part, I am satisfied here. I find that the Anglo-Saxon race is very kind to the colored race, and seem that they desire to see them better their condition as a rule. I find that they are very kind to them indeed. As I have forestated, the colored people as a race are ignorant. I am

Page 20

satisfied that some of our white folks are too premature. Our race is ignorant, as a rule, with few exceptions. The white people say, as a race, "that they are more capable to make laws and control the country than the colored race." I admit that to be true, because the colored man has not had time to develop himself; he has been kept in servitude about two hundred and forty-five years.

It is said by many that the colored race is so easy to be contented with a very little. The colored people, as a race, don't seem to have much ambition about them. I claim that it must be the way they were taught in modern times.

For an instance, if a colored man buys a house and lot, as a rule it is just as high as he desires to get. As a rule, those that have become lawyers, doctors and ministers don't seem to have ambition to want to accumulate anything more. And when one becomes a bishop, or a moderator, they fold their arms and say that they are just as high as they desire to get.

If Rockefeller's wealth were tendered to them, they would say "that they would not have it."

It seems strange, but yet it is true, they inherited Easy Street by heredity. You can readily see that several centuries have to pass before the colored people can become a race. I will admit that we have some very bright talents among the race, but it is among the few and not the many.

Page 21

My advice to them is to follow after a successful race in every particular.

I am satisfied that the day will come when they will wake up out of their stupidness and look above the dust, and look for a bright and prosperous future.

As a rule, the race goes almost crazy over religion, while other nationalities take it easy and quiet. You can readily see if the race had inherited the highest degree of civilization, they would not worship God so excitedly. You take the learned people that have inherited the highest degree of civilization: how modest they act in church and in State.

The paragraphs that I have mentioned above will show you that our race inherited their weakness by heredity. I hold that they are not in fault in every instance, but they need to be taught to act differently by some person that has been successful, like Mr. Fred. Douglas and Mr. Booker T. Washington. They can also consider the advice of the writer of this book.

Our race should not be so happy with so little.

I will admit that we all can not establish institutions and various enterprises, but we should not stop just as soon as we can read I John and II John, and get a house and lot, and other previous things, and then say we can compete with other nationalities that have established various

Page 22

kinds of enterprises and accumulated millions of dollars. We should strive to get just what they have got.

We, as a race, ought to be proud of our color. The father of wisdom and wealth was a colored man. If any one doubts my statement, I refer you to the Bible. According to the Scriptures, King Solomon was said to be a colored man. There is no person that has lived since the days of Adam and Eve ever had the wisdom that King Solomon had. Notice him in his beauty and all of his royal kingdom. His wisdom was so broadly felt that queens across the waters came to learn of his excellent wisdom. Such excellent examples as King Solomon left behind him are worthy of any race to follow after.

I simply mention this to give stimulus to the race, for it is said that the race has no example to work from, because the leaders of the Babylonian history has excluded the colored race from all greatness as to promotion. Some go so far as to say that we never had any great leaders in ancient history nor modern history. I simply mention these facts because it is necessary that we should produce proofs to show that God, in His supreme wisdom and magnitude, has not entirely obliterated the promotion of the negro race.

I love the race because I am identified with it.

Page 23

Not only do I love the race that I am identified with, but I love all races. It is said by many that the negro race's hope is obliterated in every instance, as to aspiring for great, grand and nobler things.

I endeavor to show to those that read and preserve the history of my life that these things can not bear to be tested in the golden balance. You will find in the history of my life that I have gone so far as to question the Creator of heaven as to the inability of the negro race.

Page 24

MR. BOOKER T. WASHINGTON.

DR. BROOKS

Page 25

CHAPTER IV.

MY LIFE IN COLLEGE.

My cousin and I promised each other several years ago that we would work hard and take care of our money, to enter college. We worked several years, and at the end of each year our condition was the same. We were not able to enter college. When I entered college I was not able to pay my matriculating fees. I entered college with ten cents in my pocket, after paying my railroad fare. The rule was to pay your matriculating fees and other expenses at the expiration of the mouth. During the first month I entered college, I saw Professor Inserly, one of the professors from Boston. I asked him to give me something to do to help pay for my schooling. He gave me his room to keep in order, to pay towards my schooling. Professor Perry also gave me some work to do to help pay towards my schooling. I had only one suit of clothes when I entered college, and some of the advanced students gave me some of their clothes that had been worn, and I was very proud of them. The rule in college was that all of the scholars had to dress neatly before they went to breakfast. I was unable to dress neatly like the rest. I had to

Page 26

remain in my room until all of the students had eaten breakfast. Then I went down to the dining hall and asked the cook in a sympathetic manner for something to eat. She responded to me by saying, "What are your reasons for not coming to breakfast when the others came?" I responded to her question by saying I was unable to dress neatly like the others did, for I went down in the dining hall one morning and all of the students laughed at me. I told her if she would save me something to eat every Sunday morning, I would bring her wood and water, and pick up some chips for her.

The rule was, at college, that there were fifteen minutes set apart for social hour, for the young men and young ladies. The young ladies would not allow me to walk with them; they said that I could not dress nice enough to walk on the lawn with them. I would go back to my room and get my books and study them. I asked the Lord if I would forever be in that condition.

I continued to study my books in season and out of season. While the rest would be playing on the campus and having a hallelujah time, I would confine myself to the study of my books.

I remained in that condition until the school session had expired. The scholars laughed and said I was an idiot; some said that I had a little more sense than an idiot.

Page 27

After the session had expired, I returned home and opened a pay school, which amounted to ten or twelve dollars a month. I taught school at one of Cameron's Quarters. The people were so very poor that none of them were able to board me. I had to stay at each one of the scholars' homes a night, until I got around, and continued on. Some were able to pay me for their children's schooling, and some were not.

I found out at the expiration of a school's term that I would not be able to pay my term in college. I asked the Lord what must I do. I was bound to return to college. I listened for an answer, but the Lord did not answer me directly. I formulated a new plan. I went to the store and bought me about a bushel and a half of soda crackers and fifteen pounds of sugar and ten pounds of cheese, and put in my trunk, and carried it with me to college. I hired a room from one of my friends that I was acquainted with, and asked the president to let me stay with him. The president of the institution granted my request. I carried my trunk with my crackers, cheese and sugar, and put it in the room, and that was what I ate nearly all of the session. When the chapel bell rang for supper, breakfast and dinner, I went to my trunk and got my meals. I got so very tired eating such dry food until I did not know what in the world to do.

Page 28

Sometimes I would get so very hungry, but I continued to eat what I had. Now and then I would ask my friends for a piece of meat and bread, and they would give it to me. Sometimes I would be reciting my subjects to my teacher, and I would be so very weak and hungry that I could not recite successfully. I was in that condition for several months.

I began to think that the Lord of heaven had forsaken me, and I had no friends on earth. I would write home to my people to send me some money, and they would send me five and ten cents, and oh! how glad I would be. I rejoiced to get five cents. I remember I looked up towards the heavens and prayed, and said the foxes in the woods had dens, the birds in the air had nests, and there was no place for the sinner man to rest his head. I remember I said, "Lord, hear my voice, let Thine ears be attentive to my supplications." I am satisfied that the Lord heard me, and gave consolation to a wounded heart, for I was fatherless and almost motherless, in the midst of a trying time. He made the ways possible for me.

I went to the president of the institution and told him how I had tried to make my way through school, and unless he assisted me in my struggle, I would be bound to return to my humble home and there remain until I could better prepare to

Page 29

return to school again. The president told me it would not be long before I could teach school. "You go and bring your trunk over to the dormitory, and you can stay in school until the session expires; then you can go out and teach and pay the school."

And I felt that the Lord had taken pleasure in them that fear Him, and in those that hope in His mercy, and I was satisfied that I was one among that number. I remained in school during that session. The scholars would be out on the campus enjoying themselves, and I would confine myself to my studies in my room.

About a month before the school closed, Mr. Duckett, the Superintendent of Education, held an examination, and the president of the institution excused all of the scholars that he thought worthy of going before the board. Some of the students that went before the board laughed and said, "What is the president thinking about sending Latta before the board?" They said that they were satisfied that I would fall below zero. Mr. Duckett was one of the most rigid examiners that ever examined applicants for certificates in North Carolina. I do not think I am exaggerating, because I have kept in touch with the county superintendents since that period.

As near as I can recollect, there were between twenty and twenty-five students attending the

Page 30

examination. We were on the examination almost a week, and I am sorry to say that every student, with the exception of four, made a failure. The successful ones were Dr. Williams, from Georgia; William Smith, from Tarboro, N. C.; a young lady from Lynchburg, Va., and your humble servant, from Raleigh, N. C. Dr. Williams received a second class certificate, William Smith received a third class certificate, the young lady a second class certificate, and I received a second class certificate.

After this the scholars began to assemble on the campus and say that I was not as big a fool as they thought. The President, Dr. Tupper, told the students, according to the time I had attended school, I had excelled the whole school. The scholars came to me and asked me how did I learn so fast and made such a poor appearance. I told them that men who expected to be great never put on airs to be seen, but proved that they were worthy of recognition by what they did.

After the close of the session I returned home and got a district school to teach. I taught three months and a half, and also taught night school at the same time. After paying my expenses, I had nearly a hundred dollars to return to school with. When I returned, I was able to dress very neatly indeed, and the young ladies received me very cordially on the green during social hour.

Page 31

Before I taught school it was a common saying among the young ladies and young men, "Latta"; but after I returned with a hundred dollars it was "Mr. Latta" all over the campus. I would hear the young ladies saying among themselves, "I bet Mr. Latta will not go with you--he will correspond with me this afternoon." I paid no attention to it. I said to myself, "Don't you see what a hundred dollars will do?"

The next session I was again examined by Mr. Duckett and made first grade certificate. I taught four months the following year and made one hundred and sixty dollars. When I returned to school the next session all of the students, even the professors, would say, "Good morning, Professor Latta." All of the young ladies wanted to correspond with me. They said I was so fascinating, and that my promotion was not limited. Afterwards I was promoted to hear some of the classes in the institution, as an assistant teacher, and some of those very students that laughed when I entered college recited to me before I left.

I continued to study as I did before I received the first class certificate. I studied very hard, and stayed in school about two or three years after that, as a student, and also as an assistant teacher. I taught a class in arithmetic a whole session, and enjoyed it very much. I studied so

Page 32

very hard and become so feeble that the doctor told me I must stop school.

I could not remain in school because I was overtaxed with the different subjects. I lacked almost a session of completing the different languages. The doctor said it would never do for me to attend school any longer. He said that I had enough to make out with if I never attended school another day. Had I remained in school another term I would have received my diploma.

I taught district schools, graded schools and academies. I was preparing to ask the President of the college to confer the degree of A. B. on me, excusing the few months I lost in school in completing the college course. But I continued to study at home in my room, without the knowledge of the doctor; and as I prepared myself the Lord sent an Angel to tell the President that he had completed his labor that He gave him to do, and he desired his presence around the throne. He was a faithful President, beloved by all that attended the school. He established the first institution of any note for the colored race in the Southern States. It was a sad day among the students when he said he had finished his course on earth and he desired to go home and rest from his labor.

President Tupper, of Shaw University, was a good man and a Christian hearted gentleman.

Page 32a

PRESIDENT

ROOSEVELT.

REV. M. L. LATTA.

WILLIAM MCKINLEY, Ex-President.

GROVER CLEVELAND, Ex-President.

REV. M. L. LATTA AND THREE OF HIS ADMIRABLE PRESIDENTS.

Page 33

He was a great educator and quite a scholarly man. He was beloved by both white and colored. He had the largest funeral that has been known in Raleigh for forty or fifty years. The people mourned his departure for many days. He will forever live in the hearts of the people, and especially in the hearts of all of the students that attended Shaw University.

I taught public school about eighteen or twenty years; those for whom I taught said I was a very successful teacher. The schools I taught, as a rule, were very largely attended. I was very strict as a teacher. My pupils loved me as a parent.

I always had more schools offered me than I could teach. I would be teaching in one district, and the committee in an adjoining district would save their schools until I got through teaching in the other district.

After I got through teaching school I was employed as a sewing machine agent. I sold machines about fifteen months. I found it was very easy to make sales, but hard to collect money, yet I sold quite a number during my employment. I told the people that they could not keep house without having a machine in it, and the sisters would say to me, "Brother, is that true?" and I would say, "Yes, sister; no person can keep house successfully without a sewing machine in it."

Page 35

CHAPTER V.

ALLEGED EXPRESSIONS CONCERNING THE NEGRO RACE.

It has been said by many that it was almost impossible for the negro race to do anything, and, as one member of the race, I determined, by God's help, to see if the alleged expression was really true. It is also said by the same accusers that God did not intend for the negro race to do as other nationalities. It has been so commonly spoken that God has no respect of persons. I prayed over the matter, considered it, and reconsidered it. Oh! how strange it seemed to me that a just God, that formed the heavens and the earth, and made every creeping thing--animals, man and beast! Oh! how strange it seemed to me to believe that a just God would make some races superior to others, and to stamp a seal of damnation upon a race eternally because their faces were black, and whatever they should undertake to do should fail! After studying carefully over the matter, I cried, because I knew we had a just God. It has been said that the race is prone to debauchery and detestable things in all of their actions; and yet when I read the Good Book I would see that God did not refer to

Page 36

a man because his face was black. I had heard it said to be a member of the negro race was a disgrace to human sight, because they were vicious and were not capable of doing anything that had any responsibility in it. My heart bled within me. Again I went to the Bible to see if the race that I was identified with was so condemned and had nothing to aspire for, by reason of their condition and complexion. I got down upon my knees and prayed to God, and said, "Oh, Father of Heaven and God of Love, if this calamity is true it would have been better for us if we had never been born" After I arose from my knees, praying to God in whom there is no varying to the right nor the left, and who knows no man by his condition, but measures out truth, justice and righteousness to all men alike, I found that I had great peace. I found that the burdens of these accusations would have to be made from a source of God-like power before I could accept them.

I then determined that I would take up the great responsibility to prove what had been said was not true. I made up my mind that I would begin nothing small because it had been said that a member of the negro race could not start anything requiring extraordinary ability and carry it to success--especially if ten thousand

Page 37

dollars or a hundred thousand dollars were involved.

I first thought that I would establish a university and connect it with some religious denomination. The second thought came to me, if I do that it will not begin to solve the negro problem, because the accusers would say, if it is connected with any particular denomination, that would not be evidence that a member of the colored race could do anything. They would say almost any denomination could form a combination and build an institution, because, if the colored denomination could not build the institution the white people of the same denomination would help them. The accusers would say it is easy to elect one of their members as president of the institution, and that is not sufficient evidence that the race can do anything of themselves.

Page 39

CHAPTER VI.

WHEN I COMMENCED TO ESTABLISH THE LATTA UNIVERSITY.

The white people are not enemies to the colored people, when they find out that they are doing something to better their condition. When I started to erect this Latta University many of the colored people said it was too much for one man to do, and God did not intend for one man to do that much. They called meetings and held some indignation meetings, declaring that God would be angry if one man would attempt to do that much. They invited me to their meetings. I attended some of them, and they would elect one of their members chairman and one secretary, but they were all chairman and all secretary, for they all talked at the same time. They went so far as to say that the Governor of the State of North Carolina would not allow one man to do that much to solve the negro problem.

I started out with the purpose to erect an institution for educational purposes, non-sectarian as to its religious teaching. They said it was the biggest thing they ever heard of. I knew that they, as a race, were ignorant, but they were telling the truth in that particular. They asked the

Page 40

Governor his opinion about the matter. He told them it was a very good thing if I could come out in it; but he said it was a mighty big undertaking. They called meetings for two years, until they got ashamed, and the white peopled laughed at them and said what big fools they were. They went so far as to have my name printed and circulated all over the city, saying that I was a fraud, and I never would build an institution, because they had not authorized me to build it. They said to build a non-sectarian institution I would have to go to the President of the United States and get license to build a school of that character.

The leading white people of the city told me to have them prosecuted for circulating such a paper against me without any foundation. None of them had given a dollar for the institution.

I laughed when I chanced to hear what they would say, because I knew that they were very ignorant; I knew that God had chosen some one to lead the Israelites out of Egypt, and I had begun to think that He had chosen your humble servant to lead those ignorant people out of the second Egypt. One of the ablest lawyers in the city of Raleigh told me if I said so he would put the last one of them in the work house. I remember I repeated these words to Judge Strong, and told him I believed in what Davy Crockett said,

Page 40a

THE HOUSE IN NORTH CAROLINA WHERE REV. M. L. LATTA WAS BORN.

Page 41

"First know that you are right and then go ahead." I further told him, if I would take time to fool with those ignorant colored people I would never build Latta University. In other words, I would never solve the negro problem, that I so earnestly desired to solve. I remember one morning early my physician that had been attending my family came by my home, on his way to see a patient a few doors above, and he saw my wife, as she was standing on the piazza, and he said to her, "Have you seen the papers this morning?" She replied, "No, sir; I have not seen them. What is in the papers so interesting?" His reply was, "Your husband is ruined forever. You ought to read the newspapers. Even your children and you are ruined." My wife began shedding tears, and said she wished I had never thought of building an institution. I came to the door to speak some words of consolation to her, and to tell her not to weep, because right would win. She said she wished that I had never seen an institution or heard of one, to have the people to talk about me that way. Some of her friends were visiting her at that time, and they came to the door and saw her weeping, and they began crying. It affected me so much that I almost shed tears myself. We had a sad home and there was no breakfast ate that morning. I knelt down upon

Page 42

my knees and asked them to engage in prayer with me a few moments. I took the matter to God, and after I had prayed to Him I felt more determined than I did before that I would yet build that institution, in spite of men or devils.

In a few days my family became reconciled over the matter, and said, I will leave the matter with you and God. I did not attempt to erect an institution to make money out of it. My purpose from the beginning up until the present, as far as I have gone, was to prove that the negro race could do something, regardless of color or previous condition of servitude. I have always desired, from my youth, to do something worthy of speaking of, that would be a light to the race that I am identified with.

The white people of the city published it in their newspapers that my undertaking to build a non-sectarian institution was a worthy cause. They said that it was worthy of any one's consideration. They said they knew that it was a big undertaking. They further said, if I was successful I would have credit for doing more than any man they had ever heard of, having no means to start with. They said that the colored people were ignorant and for me not to pay any attention to them. I taught school and got money to start the institution. I found that we must have some aid to enable the students to

Page 43

attend school at such rates as we do, and for that reason I had to ask the general public to help us in a small and humble way. After explaining my cause to the people, they said it was a good thing; but I found the people, as a rule, not very charitable. I found that I had to work hard enough, for ten dollars, to get a hundred and fifty dollars; but I determined, by the help of God, to accomplish my purpose.

The colored people that fought me in establishing the Latta University, and held indignation meetings against the fostering of the same, as soon as the school ran one session, came to me and said they were ignorant and were misled. They said that they had nothing against my building the institution; that they were misled by an ignorant preacher. They said if they had a plenty of such men as myself they would soon be equal to all other races. They said that I was the smartest man in the South, and not only the smartest man in the South, but the smartest man in the world. They said that no man on earth could build that institution as I did without means to start with, and they knew that I had no means to start with, and they did not want me to take all of that responsibility upon myself; they thought that I would make a failure, and it would be injurious to the race.

I had no person to give me an introduction to

Page 44

the Northern men. I was a stranger among them all. I was not so fortunate as my friend, Booker T. Washington, in having a friend like General Armstrong to introduce me to friends in the North, East and West. I had no person to loan me a dollar to start with, I admit, as my white friends and colored friends said. We have a Board of Directors, and they tried to raise money, but they could not raise twenty-five dollars, and they said, "You will have to build this school or it will not be built." So I prayed and worked. I prayed in season and out of season, and worked in season and out of season.

The State has not given the school a dollar, but it does not charge any taxes on the school property. I would work hard all day, in a half run, and sometimes running. I would be so tired when I reached my hotel I could hardly eat my supper. Many times I would find it necessary to get up out of my bed at one o'clock or two o'clock in the morning to take a train to meet an appointment at nine o'clock in the morning. I never failed in being on time.

Page 45

CHAPTER VII.

LYNCHINGS IN THE SOUTHERN STATES.

I desire to say a word concerning the lynchings in the Southern States, that our friends in the North, East and West hear so much of. I claim that it comes from ignorance among the colored people that such extreme depredations as assaulting white ladies of the South takes place. I am prepared to show you, in nine cases out of ten, it comes from ignorance. Education and sufficient moral training, with religion combined, are the only things that will stop it. I can say for this institution, as I have been the presiding officer ever since it has been founded, not a student that leaves the Latta University will ever be found guilty of such terrible conduct. I have talked with numbers of leaders that preside over various institutions, and they say not a single scholar that attended their schools have ever committed such crimes. We not only teach them intellectually, but we teach them how they must conduct themselves from a moral and social standpoint. We instill it so deeply in them until they never will forget it during life. In some instances I know several students that attended school who, when they came to school,

Page 46

were so uncouth they would almost make you blush to see how they acted. After they remained in school and received its thorough training, they would lead prayer meeting and tell others how to conduct themselves in life.

I do not believe in lynch law; but such crimes as I have mentioned above are very shocking, and sometimes a party of men take the law in their own hands. My advice in such a case is to educate such ignorant people, make the law compulsory, compel everybody to attend school, and also make it compulsory for teachers to lecture along such lines, as we do in our colleges; and if these rules that I have just mentioned are strictly enforced, we will have no trouble in these extreme depredations.

I have noticed very carefully that men of means, as a rule, are doing very little good with their money. For instance, you take men like Mr. Rockefeller and Mr. Carnegie. You will not find in a single instance that wealthy men like those give to any institution or any enterprise that is poor and needy and striving to come to the front. We must remember that we have to begin low to go high. I find those institutions that wealthy children attend are the ones wealthy men help. There is no argument that can be produced successfully to prove that such men as I

Page 47

have mentioned are helping the poor. It seems that they prefer to give to institutions that really do not need their assistance. I have been trying to help the poor. Jesus Christ said on one occasion, "The poor ye have always with you."

Page 48

MR. J. H. BIVANS, General Agent Latta University

MR. D. R. DAVIS, Former Gen. Agt. Latta University.

Page 49

CHAPTER VIII.

THE GREAT TROUBLES I HAD IN BUILDING LATTA UNIVERSITY.

We have had thousands of students to attend the Latta University. Some were able to pay their schooling and some were not able to pay their matriculation fees. There have been several thousand pupils to attend this institution since it has been founded, and we have had to carry almost one-third of them because they were unable to pay their school bills. They promised to pay their bills if we would let them stay in school, and I am satisfied that the majority tried to pay; but they were unable to do so. I had to go in debt with the merchants of the city and buy provisions to run the school. Sometimes I would go in debt so very heavy until I would have to leave school during the school term and work, rain or shine, never stopping for sleet or snow, wind or rain, raising money to pay the bills of those that were not able to pay their own bills. We charged young men only six dollars and seventy-five cents and young ladies five dollars and seventy-five cents per month. We board them and teach them, for these amounts.

You can readily see that these amounts are not

Page 50

half enough to run the school successfully. I would go up in town and see my grocerymen, and they would tell me that my bills were so very high they did not see how I ever would pay them. The bills would be so heavy, and I did not see any possible way to pay them, I could not sleep at night nor rest during the day. I many times knelt down upon my knees and shed tears, feeling that the responsibility was too heavy to carry. I remember saying several times that the responsibility was so heavy that I must decline to attempt to solve the negro problem any further. As a rule, I would remain at school during the session and go in debt several thousand dollars to run the school. As soon as school closed I would get the endorsement of the leading officers of the city and State as to the worthiness of my work, and I would take my little book in my hand, with tears in my eyes, and start out to get the necessary money. I did not know where I was going to get twenty-five cents from. I would tell the public what I was doing, and I tried to interest them to help me to meet the obligations necessary for me to meet, as to the expenses the students had incurred on the institution. I received amounts as small as twenty-five cents, and from that to a dollar. Some friends I interested enough to get five and ten dollars. Now and then some would give twenty

Page 51

and twenty-five dollars. Some would receive me very cordially and others would receive me as if I were a rattlesnake. Some would treat me very uncouth indeed, and I've had some to order me out of their places of business. I went out, but kept right on at my work, because I knew that life and death was involved in my object. I knew that they treated Christ worse than they treated me, and when I would study over the matter and knew how they treated Jesus Christ, and yet He said they knew not what they did, it inspired me to push forward. I can not explain to the public just what I have gone through during the time that I have attempted to solve the negro problem. It would worry your patience to read the oppositions and obstacles that was put in the way to stop my progress to accomplishing my purpose.

My ambition is that this institution must live when Christ shall call me to appear before His throne to give an account of my mission on earth.

I sincerely hope that the institution may do good through all ages to come. I desire that the institution may be a monument to the fact that a member of the negro race has solved a serious and an important problem--one that all nations doubted as to its consummation.

It will be seen that the contributions of the people amounted to very little, and you can

Page 52

readily see, if it meant anything, it meant work from the beginning and also ability to conduct and manage the affairs. I claim that the race problem is solved. I am satisfied that, after the general public reads the history of my life, they will say that it is the biggest undertaking of any one man in ancient or modern history.

Often my heart ached within me, and I shed tears time and again. I would walk along the road and weep. I would kneel down and pray, trying to find out if it was true that a just God would make a race and shut the doors of prosperity against them because their complexion was different from other nationalities. I said if I would manage the enterprise discreetly and be prudent in all of my actions, practice economy and be energetic, seeing that every dollar goes to its proper place--when I shall have exercised all of that care and discretion and attended to everything judiciously, and failed, then I would plainly see that God did not intend for the colored people to compete with other races.

But I can say, after undertaking such great responsibility, beyond all question, that we have a just God, and a man can accomplish just what he desires to accomplish and be second to none.

Now I can say, as Patrick Henry said, "I have but one lamp, by which my feet are guarded, and that is the lamp of experience." I could not

Page 53

speak so determined on this matter as I do but for my experience, and, remember, experience is the thing after all.

In taking this task upon myself, it was not my purpose to assail any particular race; but after hearing so many accusations and criticisms that I had heard, I determined to see whether it was true or not. I am now satisfied that God works in mysterious ways His wonders to perform.

Read the history of the children of Israel when they were under the hard taskmasters of King Pharaoh in Egypt. It is said that the Israelites that were brought out of bondage, under the administration of King Pharaoh, are Hebrews. Some have said, it seems strange that God would allow the Israelites to suffer as long as they did, being persecuted and evil-treated, and also laboring under the influence of maltreatment, before Moses led them. from under the Egyptian's bondage. They say it is cruelty on the part of creation, and it is admitted by all of the Hebrews that the struggle for liberty away back in the Moses dispensation is what has made them the most successful nationalitythat is upon the globe to-day.

You might trace the Ethiopian race in the same way. A great many people have said that God was not just, allowing other nationalities to

Page 54

predominate over them and hold them as slaves. I simply mention these statements to show that God works things to suit Himself, and if God, in His own mysterious ways, in managing things, has promoted the Hebrews to prosperity, then it is prima facie evidence that the same God that promoted the Hebrews will promote the negro race, if we will faithfully discharge every duty that devolves upon us.

Page 55

CHAPTER IX.

PROGRESS OF THE LATTA UNIVERSITY.

Latta University is located in West Raleigh, N. C., one mile west from the capitol building. The location is the very best that could be desired for this school, being outside the busy city, but within easy reach by means of the electric street cars, which run near the institution. It is one of the largest schools in the South in every respect, having capacity to accommodate more than fourteen hundred students. We have twenty-three buildings on the campus.

Latta University was incorporated by the laws of North Carolina, February 15, 1894. The property of the University was purchased in 1891, and the school was founded in 1892. The institution is wholly non-sectarian in its religious instruction and influence, yet earnest attention is given to Bible study, applying its truths to daily life and conduct, that a thoroughly Christian character may be attained. It is open to all students of either sex.

The Industrial Department gives special opportunities to young men. By working on the industrial farm they receive all the privileges of the boarding department. Rooms, bedsteads

Page 56

and mattresses are furnished free. Heat and light and washing also furnished free. The advantages of the Night School and the opportunity of earning from eight to ten dollars per month, to be placed to their credit account and applied to their board account, are open to all.

No student under sixteen years of age will have admission to the Industrial School. Students must be healthy and able to do farm work. Students who do not abide by the regulations, and who do not give satisfaction in their work, are not retained in school, and on being sent away forfeit their right to any part they may have earned.

All work, even that which is remunerative, is instructive and methodical and under experienced supervision. Those desiring to work enter the Industrial School, which runs ten months. Those who are not prepared go to the Night School and work out a part of their schooling. This is done so all persons can have an opportunity to get an education.

In some extreme cases, when we find that a worthy person desires to get an education and is deprived of necessary means, we make it convenient for them to work their way through school. Young men are taught to do all kinds of carpentry work and brick laying. Those who enter the Industrial School with the intention of working

Page 57

their way through school, only have permission to attend the Night School, and they are required to pay $4.00 for incidental fees.

The school runs day and night. It will be optional with the school as to which department these students attend--day or night school. Both are taught by experienced teachers.

Young ladies who enter the Industrial Department are taught to do laundry and all kinds of house work.

There is no school for the benefit of the race which has had so humble an origin as this, and yet (if signs mean anything) it is destined to be one of the foremost for the elevation of our people.

This institution is for the race, and the first which has been organized under like circumstances, with a representative of the race at the head.

I can not forget to thank the generous white people of the "Old North State" and elsewhere who have so kindly helped me in this work, and, while thanking them for the past, I earnestly plead for their aid in the future, and for the cooperation of my own race.

When I shall have completed the task on earth which God gave me to do, and when He shall require my presence in heaven, to remain with Him forever, this school must be carried on for the

Page 58

educational purposes for which it was founded. It must remain as Latta University, for educating and helping a weak race, and to remain as a monument to show the work that I have done for the race, and to show that I am not dead, but simply sleeping.

I am satisfied that my task will soon be ended on earth, and God will send an angel to summons me to appear before His throne. I hope to be able to look back over a well spent life and feel satisfied beyond a reasonable doubt that I have faithfully discharged my duty in lifting up a fallen race and in doing good for the public in general whenever it has fallen to my lot.

I am satisfied that man can not compensate me for my services on earth, and, therefore, I am looking to God for reward for what I have done in the past and what I shall do in the future.

We had twenty-six buildings and lost three by fire. The library of the school was also burned.

Page 59

CHAPTER X.

THE INVESTIGATION BUREAU.

I have made it a rule of my life, whenever a good cause is presented to me, to help it along. I never fail to do something for it, if I can. I find, in my experience, which is the only lamp that my feet are guided by, whenever a person wants to help lift up fallen humanity, and has not the means to make a great display like those that have plenty of means, that there is a combination formed under the same head, like the great monster, which is called "Trust."

I desire to say something concerning the Investigation Bureau in New York, as they call it, which I claim does not do any good, but pays men for nothing but to go around the country to find institutions that are just struggling for life, doing the best they can, with limited means. If they find an institution of that nature that can't sit alone, nor crawl, they report to a class of men who do not desire to help any such, but desire to give to enterprises that do not really need it. In other words, they do that to prevent giving to any cause, only a few dollars to the New York Investigation Bureau. If a person asks them to give to a cause, which is endorsed by the

Page 60

leading men of the town or city from which they come, or to institutions endorsed by men that are filled with patriotism, men whose integrity is so high that they could not afford to give their sanction to a fraudulent purpose, men who are chosen among the people in the community in which they live to represent the people; and yet these fellows of the New York Investigation Bureau turn down these prominent men, such as our Mayors, Clerks, Judges, and even the Governor of our State. Is it just that the statements of these good, patriotic men should be repudiated, when they are disinterested, having only a desire to see a good cause promoted?

I am satisfied that I have done more good along the lines of education for the advancement of my race than any of these. I have had hundreds of orphan children in our institution and hundreds and thousands of others that needed help. Some have finished their education and some have not.

I have noticed very carefully as to the proficiency of the students of the Latta University. Of course they do not fail before the Board whenever they desire to teach a public school. Not only the graduates, but the students that desire to teach. Several hundred of them have made application to teach in the public schools, and they did not make a failure, for I have made it

Page 61

a rule to keep in touch with the students that attend the institution and see that they are properly prepared.

I desire to call the reader's attention to these suggestions. Suppose, when we had two or three small school buildings, and the school was in its infancy, I should have stopped working then, simply because the Investigation Bureau said it was not worthy, for it helped students to pay their tuition?

I find that the majority of the people, as I present my cause and tell them, would say, whenever a cause is presented to me, endorsed by the leading people of the community, that is satisfactory, without receiving information from the Investigation Bureau. I claim that I have been the means of uplifting more ignorant people out of the gutter and promoting them to usefulness and a higher moral sentiment than all of the Investigation Bureaus in New York, or any other place. I am proud to say, by the help of the Creator of heaven and earth, by push and faith, by persistent efforts against all odds and attempts to demoralize me, I have succeeded. The institution has extended its wings with the intention to climb the topmost ladder. It has extended its breadth; it has closed the door of

Page 62

seclusion and is aspiring to the noble efforts that makes the nation useful and great.

Surely the Investigation Bureau have not read the Commandments of God. If you educate and thoroughly train the mind of ten persons, you have done a remarkable deed.

I desire to call the attention of the Investigation Bureau to one grave fact: God told Lot that he would save the great cities of Sodom and Gomorrah if he would find ten just persons in them. We claim that we have not only made ten persons upright and good, but we have had several thousand to attend the Latta University, and the greater portion have been made good and just by the influence of the institution.

Page 63

CHAPTER XI.

THE DISTINCTION MADE BETWEEN THE WHITE

PEOPLE AND COLORED PEOPLE OF THE

NORTH AND SOUTH.

Thank God the University has prospered in its administration. The institution owns nearly three hundred acres of land on the suburbs of the city. A portion of the land cost four hundred dollars an acre, and we have been abundantly blessed. I visited all of the principal towns and cities of the Southern States. My purpose for doing so was to see if the white people were antagonistic to the colored people. I had an interview with all of the business white people. I presented my cause to them, and told them what I was doing. They said it was a good cause and worthy of support. I found that they were not antagonistic to the colored people, but willing to help them.

Of course the Southern people have not the money that our Northern, Eastern and Western people have; but they gave to me very liberally and treated me very nicely indeed. I knew that it was not a custom in the South for colored

Page 64

people and white people to put up at a hotel together. Knowing this, I always went to some of the respectable colored people and stayed with them. I like the Southern white people for the independent stand they take. They come right out in plain English and say that they do not receive colored people in their hotels, for they say that they never were brought up to mingle with the colored people, and will not do so.

There is a big difference between the North and South concerning the colored people.

It is indiscreet to bring about social equality among the two races in the Southern States, because, in the first place, the colored man is ignorant, with few exceptions. In the second place, the colored people have not had time to develop themselves.

For my part, I do not want social equality, for I do not have time to enjoy social life with my own family as I would like to do. My advice to the colored people is to get the mighty dollar and buy property, and they will have all of the recognition that they want. The colored people, as a race, are the worst enemies to themselves. They are prejudiced towards each other. If one tries to go to the front the others will try to keep him back. These dispositions many of them inherited, and can not help it. I must say

Page 65

this much for the white people of the South: if they see the colored man trying to do something to better his condition, they are willing to assist them, and not only willing to assist them, but they do assist them.

It will take several generations, as I have said, before the colored people, as a race, will be able to compete with other nationalities. It is not their fault, because they can not compete with other races, but the condition, that they are in as a race.

I was travelling through the West when establishing our institution, and remember that while lecturing and preaching at several churches to have preached in Cincinnati in one of the largest churches in that city. A very distinguished minister, pastor of the church--I can not think of his name at present--but his church gave me a hearty collection. They seemed to be very well pleased with my sermon, as if they enjoyed it. They took up a collection for me. I talked with the pastor for a few minutes, and told him that I would leave the next day for the city of Chicago. He told me to come to his study before I left, he wanted to see me. I went to his study, and he said to me, "You are engaged in a laudable cause. It is worthy of the consideration of any one." He gave me twenty dollars, and said, "I have read

Page 66

ancient history and modern history, and that is the biggest undertaking for one without means I have ever read or heard of." He said, "My dear brother, when you get that institution in operation please write me, and I will send you a check for forty dollars." As much as to say that I would never complete my object. About fourteen months from the time I met him, the school opened with a very large attendance. I notified him, according to his request, and told him that we had opened school with a large number of students, and had erected six buildings on the campus. He said in the communication that he sent me: "I would not tell you what I thought when you and I were talking in my study. You have surprised me very much indeed. I thought it was entirely out of the question for you to accomplish such a great work without several thousand dollars to start with. Enclosed please find a check for forty dollars. I sincerely wish you much success in your worthy cause."

Since I have attempted to establish the Latta University I have visited almost every city and town in the United States; have had an interview with almost every leading business man in the city of New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, and in the city of San Francisco, Boston and Cincinnati, besides interviewing many business men in all

Page 67

the important towns, cities and villages in the United States. My purpose for doing so was to present the negro problem, because I had made up my mind to study the negro problem thoroughly, if it cost my life. I desire to explain to the public how the people received me this side of Mason and Dixon's line and in the North, East and West. In some of the cities and towns of the North the hotels received me very cordially and some did not. After I completed my work during the day I would go to some hotel, and often would walk until 12 o'clock at night trying to get a place to stay. I would go to the hotel and tell the clerk that I wanted to be accommodated. The clerk would tell me that all of the rooms were occupied. I would go to another hotel, and the clerk would tell me the same. I would go to another and the clerk would tell me the same.

It appeared to me to be somewhat singular, and I made up my mind to notice and see if some one else would ask for accommodation. I stepped aside, about ten or twelve yards, and stood up beside a lamp post. At that time I was so fatigued I did not know what in the world to do. I made up my mind that I would have to go and ask the police for quarters. The last hotel that I went to was about one o'clock. A train

Page 68

came in at 1.30 o'clock and about fifteen persons came to this hotel and asked for accommodations. When they went into the hotel I peeped in, but kept in the dark, so no one could see me. As soon as they got in the clerk gave them the register, and every one of them entered their names, and he told the porter to show them their rooms. I then went down the streets with tears in my eyes, to think how I was treated just because my face was not as white as those that came in on the late train.

I thought about what Fred. Douglas said, that he made up his mind to leave the Southern States for protection, in one of his great speeches in Boston, that I listened to very carefully. He said, when he got on the Potomac River the Northern people kicked him on the northern side and the Southern people kicked him on the southern side, and they kept him in the middle of the river all the time. Mr. Douglas said that the people would invite him to preach and a large audience would turn out to hear him, but when he got through preaching no one invited him home. He said he got so hungry that he did not know what to do. He said, "the foxes in the woods had dens and the birds in the air had nests, but poor sinner, man, had nowhere to rest his head." When I heard him make that

Page 69

speech I had just strated out on my mission. In many places I visited there were no colored people, or, if there was, I did not know where they lived. I knew that they did not refuse me because I did not appear respectably, because I always made it a rule to appear well. I remember, in many instances, I would walk from one to two o'clock, meeting scarcely any one but the police, my heart heavy, body worn out and nowhere to rest my head.

I would think of what my friend Douglas had said when he made that speech. I said, surely, surely, I will never come to that.

I remember when, in one of the largest cities in the coal region, in the State of Pennsylvania, I looked up toward the heavens and said, "I am not even as comfortable as a dog, because the dog had a place to rest, but there was no place for poor me to rest my head." This is the history of my life all through the North, East and West, because I was identified with the Ethiopian race.

On one occasion I was travelling through the West, and a teacher of the institution that I preside over as President was with me. We stopped over at a town for three or four hours, where we had some business to attend to. I went to a very small house, called the Mansion House.

Page 70

Nearly all boarding houses and hotels have liquor saloons attached to them. The clerk was selling whiskey to his customers. He saw us as we were coining towards this Mansion House, and he and his customers came to the window and stared at us as if we were a circus. The teacher and I went in the office. I asked the clerk would he let the teacher remain there two hours, until the arrival of the next train, as we were going to the West. He commenced talking to me, in the presence of the rest, and afterwards told me that he wanted to see me privately. He said the proprietor told him not to receive any colored folks, nor even let them go in his dining room. I knew that was too far from civilization. I asked him where was the proprietor, and he told me he was out at his livery stable. I went to the stable and saw the proprietor. He looked as if he did not want to see a colored man. I approached him, but found it was necessary to let him know just who I was. I told him we only wanted to stay two or three hours, until the arrival of the train. He told me to go back and see the clerk. I told him the clerk told me to come and see him. After I informed him who I was and told him my profession, his appearance changed, and he kindly consented for us to remain until the arrival of the train. His wife would hardly speak to the teacher during her stay; but her

Page 71

little daughter stayed around her and tried to make it pleasant for her. The proprietor's wife saw that the little girl was interested very much in the teacher, and she, too, tried to make it agreeable for her. After we had taken dinner, we bade them good-bye.