The Life and Speeches of Charles Brantley Aycock:

Electronic Edition.

Connor, R. D. W. (Robert Digges Wimberly), 1878-1950

Poe, Clarence Hamilton, 1881-

Funding from the Institute for Museum and Library Services

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Melissa Meeks

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc., Melissa Meeks and Natalia Smith

First edition, 2002

ca. 640 K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2002.

Source Description:

(title page) The Life and Speeches of Charles Brantley Aycock

(cover) The Life and Speeches of Charles B. Aycock

(spine) The Life and Speeches of Charles B. Aycock

R. D. W. Connor

Clarence Poe

xxiii, 369, [1] p., ill.

GARDEN CITY NEW YORK

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

1912

Call number CB a 97C c.16 (North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been entered using double-keying and verified against the original.

The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

All footnotes are inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings

Languages Used:

- English

- German

- Latin

LC Subject Headings:

- Governors -- North Carolina -- Biography.

- North Carolina -- Politics and government -- 1865-1950.

- African Americans -- Suffrage -- North Carolina.

- Aycock, Charles B. (Charles Brantley), 1859-1912.

- North Carolina. Governor (1901-1905 : Aycock)

- Education and state -- North Carolina.

- Democratic Party (N.C.).

Revision History:

- 2002-09-27,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2002-01-31,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2001-12-11,

Melissa Meeks

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2001-11-20,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

[Spine Image]

[Cover Image]

[Half-Title Page Image]

AYCOCK IN HIS LATER YEARS

This is the last photograph taken of him.

[Title Page Image]

[Title Page Verso Image]

THE LIFE AND SPEECHES

OF

Charles Brantley Aycock

By

R. D. W. CONNOR

Secretary North Carolina Historical Commission and Author of

"Cornelius Hornett, An Essay in North Carolina History," Etc.

and

CLARENCE POE

Editor of "The Progressive Farmer," and Author of "A Southerner

in Europe." "Where Half the World is Waking Up," Etc.

GARDEN CITY NEW YORK

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

1912

Page verso

Copyright, 1912, by

MRS. CORA W. AYCOCK

All rights reserved, including that of

translation into foreign languages

including the Scandinavian.

Page v

To

The Boys and Girls of North Carolina

whom he loved, for whose development he

so passionately yearned, and for whom

he ever gave the gladdest service

of his heroic life,

This Book is dedicated

Page vii

PREFACE

We have earnestly sought throughout this book to avoid writing in a spirit of eulogy or in a spirit of partisanship. We should like for every North Carolinian to know Aycock as he really was. As he said but a few months before his death in introducing Mr. William J. Bryan: "It has never been my custom in presenting a speaker to an audience to eulogize him. If he needs it, he does not deserve it; if he deserves it, he does not need it." The authors have sought to write with a full recognition of this fact. If despite our efforts our volume still appears eulogistic, it is not our fault, but because the mere faithful delineation, an untouched negative of his character, as it were, itself gives that impression. It would, in fact, be an indictment of the people of North Carolina if the man best beloved among them of all his generation had not possessed such a character. We can only assure the reader that we have sought to hold the mirror up to nature. In what we have said in this chapter about unselfishness and sincerity as the keynote of his character, for example, we have simply recorded the undoubted facts as they are -- writing no more in a spirit of eulogy than we shall write in a spirit of criticism in recording the fact that as Governor he probably pardoned too many prisoners, or as a lawyer was not methodical in business.

Page viii

We have also sought to avoid partisanship. Nevertheless, the fact remains that Aycock was a party leader and that he was an intense, insistent, unyielding, even if never bitter or vindictive, partisan. It has been necessary for us to record the facts as we see them -- and, in the main, as he saw them -- about the times in which he lived. If any statement we have made seems partisan, it is only because the bare record of the fact as we see it, itself seems partisan; and we would always have it remembered that we have set down nothing in bitterness but everything in candor.

The authors cannot too heartily thank the scores of friends of Governor Aycock who have aided us. Without their help this volume could not have been prepared. First of all, Judge Robert W. Winston should be named. We return especial thanks to Judge H. G. Connor for the chapter on "Aycock as a Lawyer" which we have inserted substantially as he wrote it. A partial list of the others to whom we are under especial obligations follows:

Dr. K. P. BATTLE, Chapel Hill; MARION BUTLER, Washington; Prof. E. C. BROOKS, Durham; Rev. W. C. COLE, Chapel Hill; W. T. CAHO, Bayboro; HUGH CHATHAM, Winston-Salem; R. D. COLLINS, Linden; JOSEPHUS DANIELS, Raleigh; R. A. DOUGHTON, Sparta; J. D. DAVIS, Fremont; C. C. DANIELS, Wilson; Judge F. A. DANIELS, Goldsboro; A. H. ELLER Winston-Salem; Rev. J. H. FOY, Roseville, Cal.; Dr. J. I. FOUST. Greensboro; Ex-Gov. A. B. GLENN, Winston-Salem; JONATHAN HOOKS, Fremont; Rev. J. D. HUFHAM, Henderson; J. ALLEN HOLT, Oak Ridge; ARCHIBALD JOHNSON, Thomasville; Dr. J. Y. JOYNER, Raleigh; Rev. LIVINGSTON JOHNSON, Raleigh; Bishop J. C. KILGO, Durham; J. D. LANGSTON, Goldsboro; FRED. A. OLDS, Raleigh; P. M. PEARSALL, New Bern; Dr. ROBERT. P. PELL, Spartanburg, S. C.; J. R. RODWELL, Warrenton; Miss FRANCES RENFROW, Raleigh; Bishop EDWARD RONDTHALER, Winston-Salem;

Page ix

WESTCOTT ROBERSON, High Point; M. L. SHIPMAN, Raleigh; Dr. C. ALPHONSO SMITH, Charlottesville, Va.; FRANCIS D. WINSTON, Windsor; Dr. GEO. T. WINSTON, Asheville; C. S. WOOTEN, Mt. Olive; Prof. H. H. WILLIAMS, Chapel Hill.

It should be added that where any reference to either of the authors has seemed necessary, the author named second herewith has used the term "the writer," and the author first named some other designation.

R. D. W. CONNOR.

CLARENCE POE.

Page xi

CHRONOLOGY

- 1859 November 1st, born in Wayne County near Nahunta (now Fremont). Parents: Benjamin Aycock, Serena Hooks Aycock.

- 1875 August 21st, his father died.

- 1876 At school at Nahunta, Wilson, and Kinston.

- 1877 Entered the University of North Carolina.

- 1879 Made his first public address in interest of education in Mangum Township, in what is now Durham County.

- 1880 Graduated at the University in June, winning Bingham Essayist Medal and Willie P. Mangum Medal for best graduating oration. In summer and fall canvassed Wayne County for the Democratic ticket.

- 1881 Began practice at law in Goldsboro with Frank A. Daniels. May 25th, married Miss Varina Davis Woodard of Wilson. July, elected Superintendent Public Instruction for Wayne County.

- 1888 Canvassed his Congressional district as Cleveland presidential elector, winning distinction as a political debater and a student of the tariff.

- 1890 Candidate for Congress before the Democratic Convention which named Hon. B. F. Grady.

-

1891 Married Miss Cora L. Woodard, younger sister of his first wife, who had died the previous year.

Page xii - 1892 Elector-at-large on the Cleveland ticket; canvassed the State with Mr. Marion Butler, Populist nominee for elector-at-large. August 14th, his mother died.

- 1893 Appointed United States District Attorney for the Eastern District of North Carolina, which position he held till 1897.

- 1894, 1896 Again canvassed the State for the Democratic ticket.

- 1898 May 12th, sounded the keynote of the "white supremacy" campaign in speech at Laurinburg with Hon. Locke Craig. Became known as the most effective Democratic speaker in this campaign, his debates with Dr. Cyrus Thompson becoming historic.

- 1900 April 11th, unanimously nominated for Governor of North Carolina, all other candidates withdrawing before the convention met. Became the leader in the campaign for the adoption of the constitutional amendment for eliminating negro vote, promising the people that if elected Governor he would wage a persistent campaign for public education.

- 1900 August 2nd, elected Governor by the largest majority over opposition ever given a candidate in North Carolina -- 60,354.

- 1901 January 15th, inaugurated Governor. Immediately began a campaign for improving the State's public schools.

-

1904 His campaigns for public education having attracted national attention, he was invited by educational authorities of Maine to canvass that State in behalf of the schools. He was accompanied in this canvass by Hon. Francis D. Winston.

Page xiii - 1905 January. He returned to Goldsboro as a private citizen, resuming his law practice with Hon. Frank A. Daniels. June 14th, received degree of LL. D. from University of Maine.

- 1908 One of the leading speakers in the campaign for State-wide prohibition.

- 1909 January. Moved to Raleigh, forming law partnership with Hon. Robert W. Winston. This partnership existed until Aycock's death.

- 1911 May 20th, announced himself a candidate for Democratic nomination for United States Senate.

- 1912 April 4th, died suddenly in Birmingham, Ala., while addressing the Alabama Educational Association on Universal Education. April 7th, buried in Oakwood Cemetery, Raleigh, N. C.

Page xv

CONTENTS

- PART I.--LIFE OF AYCOCK

- Preface . . . . . vii

- Chronology . . . . . xi

- Introduction . . . . . xix

- I. Ancestry, Boyhood and Early Education . . . . . 3

- II. From Farm Boy to University Leader . . . . . 21

- III. The Foundations on Which Aycock Built His Character . . . . . 32

- IV. Aycock as a Lawyer . . . . . 44

- V. The Menace of Negro Suffrage . . . . . 61

- VI. The Suffrage Campaign of 1900 . . . . . 73

- VII. A Progressive Administration . . . . . 90

- VIII. "The Educational Governor" . . . . . 111

- IX. Aycock's Ideals of Citizenship and Public Service . . . . . 140

- X. Aycock the Southerner: His Attitude Toward the Negro and Toward Sectional Issues . . . . . 153

- XI. Aycock the Man: His Relations to His Friends and His Fellows . . . . . 164

- XII. Intimate Glimpses of Aycock: Personal Traits, Tastes, and Characteristics . . . . . 177

- XIII. Aycock's Later Years and His Candidacy for the Senate . . . . . 189

- XIV. His Last Days and His Relations to His Family . . . . . 204

Page xvi - PART II.--AYCOCK'S SPEECHES

- I. The Keynote of the Amendment Campaign: Speech Accepting the Nomination for Governor. (1900) . . . . . 211

- II. The Ideals of a New Era: Inaugural Address. (1901) . . . . . 228

- III. A Message to the Negro; Address at Negro State Fair. (1901) . . . . . 247

- IV. Speech Defending His Policies and Administration: Democratic State Convention. (1904) . . . . . 252

- V. The South and the Union: Speech at Charleston Exposition. (1902) . . . . . 268

- VI. The Genius of North Carolina Interpreted: Greensboro Reunion Speech. (1903) . . . . . 272

- VII. How the South May Regain Its Prestige: Address at Southern Educational Association. (1903) . . . . . 279

- VIII. Aycock on the Hustings: A Typical Campaign Stump Speech. (1910) . . . . . 287

- XI. Robert E. Lee: Address. (1912) . . . . . 309

- X. Universal Education: Unfinished Speech at Birmingham, Ala., April 4, 1912 . . . . . 316

- XI. A Last Message to the People of His State: Address Prepared for Delivery in Raleigh, April 12, 1912 . . . . . 325

- Index . . . . . s365

Page xvii

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- Aycock In His Later Years . . . . . Frontispiece

- Benjamin Aycock . . . . . 8

- Serena Hooks Aycock . . . . . 16

- Aycock As a Young Man . . . . . 24

- Old South Building, State University . . . . . 28

- Aycock As He Appeared While Governor . . . . . 214

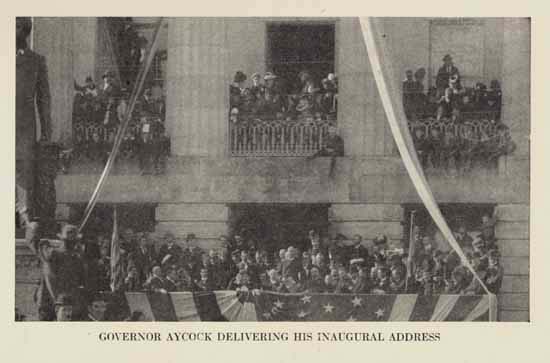

- Governor Aycock Delivering His Inaugural Address . . . . . 238

- Outline for Governor Aycock's Universal Education Speech . . . . . 322

Page xix

INTRODUCTION

IN LOOKING over the completed chapters of this volume, that which seems to stand out clearest, even where our first aim has been to record achievements and labors, is the personal character of Governor Aycock. It is well if this is true. It is, in our opinion, not his greatest distinction that he was at one time Governor of North Carolina and one of the greatest of our Governors, nor yet that he was a leader in a great revolution that established the political supremacy of the white race in North Carolina, and in another revolution that made universal education forever "a matter of course instead of a matter of debate" in the Commonwealth. His greatest distinction is rather that he was the most beloved North Carolinian of his generation.

The heritage of Aycock's achievements is indeed a treasure which his mother State will cherish, proudly and lovingly, for many generations to come; but even finer than the heritage of his achievement is the heritage of his character.

Aycock not only won the support of his fellows, but he won their trust. He not only won their trust, but he won their love. "Love," we know, is not a word that comes easily to a man's lips in speaking of other men. "He was my friend," "He is a man I always admired," "He is the man I am supporting" -- so the

Page xx

phrases usually run. But such words did not express the feeling of the people of North Carolina for the man whose life-story this book tells. When the mournful news of his death was flashed over the wires from Birmingham, not a mere select number of friends, but thousands and thousands of sturdy, rough-featured men from the mountains to the sea, from day laborers to millionaires, said in husky tones, "I loved Aycock." Scores and scores of strong men in all walks of life have sent us reminiscences for publication in this volume -- quiet men, not given to sentiment and averse to effusive speech -- and through them all runs the same vein of feeling, "We loved Aycock and the people loved him."

In fact, the knowledge of the hold that he had upon the affections of the people was one of the greatest happinesses of his latter years. The fact comes out humorously in his Asheboro speech: "Bless your life, I was for a man for Governor two years ago and he got beat. Men on the other side said I was trying to force his nomination because I had been Governor and every-body loved me. And I believe everybody did love me. But as soon as they got that report out, they went and voted for the other man just to show me that I couldn't run them."

Inevitably the question presents itself: What was the cause of this distinction? Why did North Carolinians admire other leaders, but love Aycock? And the answer must be, it was a case of love begetting love. He never knew what it was to cringe before the people for their favor or bend the knee that thrift might follow fawning. He would not have flattered Neptune for

Page xxi

his trident, or Jove for his power to thunder. But Aycock, as Governor Jarvis said, "had, like Vance, a genuine love and affection for all the people of the State." His great heart simply overflowed with love for "folks" -- he would have preferred this homely term instead of "people" -- for all sorts and conditions of "folks"; and men simply measured to him again as he had meted to them. It was only six days before his death that a friend brought to his attention a saying of Tolstoi's: "We think there are circumstances when we may deal with human beings without love, and there are no such circumstances: you may make bricks, cut down trees, or hammer iron without love, but you cannot deal with men without it." And his career affords striking proof of the truth of Tolstoi's saying. Editor Archibald Johnson stated the truth at the time of Aycock's death: "The secret of his strength was that he was a great lover. His heart was as tender as a woman's, and warm and true. His affection for the State was a passion that glowed perpetually." And this love for his fellows which was Aycock's ruling passion -- how completely it measured up to the requirements set forth by the great Apostle to the Gentiles: unselfish, "seeketh not her own, envieth not"; sincere, "vaunteth not itself and is not puffed up"; and "thinketh no evil." As an official he regarded his first duty as being to the State; as a man, to his fellows; as a Democrat, to his party; as a husband and father, to his family; as an humble Christian, to his God. He found absolutely no relation in life in which he could think first of self.

His next most remarkable trait was his absolute freedom from all pretense. As has been so well said of

Page xxii

him, he had "the simplicity of sincerity and the sincerity of simplicity."

We emphasize these things because after the intimate study of all phases of Aycock's life required in the preparation of this book, it is our conclusion that while it is well for every North Carolina boy and girl to know of Aycock the Governor, Aycock the party leader, and Aycock the educational crusader, it is even better for them to know Aycock the man.

In the finest passage in his "French Revolution," Carlyle recounts the deeds (and misdeeds) of the dead sovereign of France and then moralizes wisely: "Man, Symbol of Eternity, imprisoned into time, it is not thy works which are all mortal, infinitely little, and the greatest no greater than the least, but only the Spirit thou workest in, that can have worth or continuance."

It is not because of the offices he held, not because of the power he exerted, but because of the spirit he worked in that the echoes of Aycock's influence, in the language of his beloved Tennyson, will --

"Roll from soul to soul

And grow forever and forever"

in the State he loved and served. Not every boy who reads this volume can hold high office as Aycock held it. There is but one North Carolinian at the time among our more than two millions who can sit in the office of Governor. Not every one can sway the people as Aycock swayed them. To but one man in a generation is it given to have the love and loyalty of the people as he had them, and even his great heart and great brain could not have won for him such influence

Page xxiii

had not a crisis in the State's history also brought the opportunity for the fullest exercise of his powers. But to work in Aycock's unselfish spirit for the upbuilding of North Carolina, to share his passionate yearning for the uplift of all classes of our people, to fight always, as he fought, for "the equal right of every child born on earth to burgeon out all there is within him," and to feel, as he felt, that every civic duty, whether exercised by the humblest voter or the highest official, is a sacred trust to be used never for one's own aggrandizement or profit, but only for the public good -- these things all of us may do, and they constitute the teaching of Aycock's life.

Page 1

PART I

LIFE OF AYCOCK

Page 3

The Life and Speeches of

Charles B. Aycock

CHAPTER I

CHARLES BRANTLEY AYCOCK

ANCESTRY, BOYHOOD AND EARLY EDUCATION

THE ancestors of Charles Brantley Aycock were plain, simple farmers who cared nothing for genealogies and preserved no family records. However, the constant reappearance of the same family names through several generations enables us to trace the line of his ancestors back to colonial times with some degree of accuracy. They were among the earliest settlers upon the fertile lands that lie along the upper waters of Neuse River, and its tributaries, in what is now Wayne County, North Carolina. It appears that, some time prior to the Revolution, members of the family migrated to that section from the northeastern end of the colony. William Aycock, the first of the name in the colony of whom we have record, entered upon a grant of five hundred acres in Northampton County in the year 1744. After that date the records of the colony mention others whose names indicate a close family connection. Among

Page 4

them, besides William, were Francis, Robert, John, and Jesse, all of whose names reappear among the brothers of Charles B. Aycock. Two of these Aycocks, Robert and John, were soldiers of the Revolution.

Governor Aycock's great grandfather was probably Jesse Aycock, whose name appears in the Federal Census of 1790 as the head of a family in Wayne County, which, in the language of the Census, consisted of two "free white males of sixteen years and upward," four "free white males under sixteen years," and two "free white females" -- probably himself and wife, five sons and one daughter. He owned three slaves. The grandfather of Governor Aycock, also named Jesse, married first a Miss Wilkinson, and by her became the father of six sons, one of whom was Benjamin, the Governor's father.

The line of Governor Aycock's maternal ancestors, beyond the third generation, is equally obscure. His great grandfather was probably the Robert Hooks whom the Census records as head of a family in Wayne County in 1790, consisting of one "free white male" over sixteen, three "free white males under sixteen," and one "free white female." That he was a man of considerable wealth, as wealth was then counted in that community, is indicated by the fact that he was the master of fourteen slaves. In all Wayne County only twenty-seven persons owned a larger number. His son, Robert Hooks, married a Miss Bishop, by whom he had four sons and three daughters. The eldest of the daughters, Serena, married Benjamin Aycock, and became the mother of Charles Brantley Aycock.

Page 5

Benjamin Aycock, a man of great reserve and dignity, was a fine product of that sturdy, law-abiding, industrious rural population which has always formed the backbone of North Carolina, and has given to the State her most marked characteristics. He loved the simplicity and independence of rural life, and inculcated in the members of his family habits of economy, thrift and industry. His neighbors esteemed him for his honesty, his fine common sense and practical wisdom, and for his great strength of character. He served the people of Wayne County for eight years as Clerk of the Superior Court, and in 1864 and 1865 represented them in the State Senate.

His service in the State Senate was not without significance and interest. There was nothing of the politician about him. He performed his duties in the same straightforward, uncalculating manner, and with the same unyielding courage of conviction -- as a single instance will illustrate -- which so strongly characterized the public career of his more distinguished son. In 1864 the relations existing between the State Government and the Confederate Government bordered upon open hostility. The passage of the Conscript Act by the Confederate Congress had aroused intense opposition in North Carolina. Governor Vance, though determined to enforce the law, was known to believe it unconstitutional. A majority in both Houses of the Legislature not only believed it unconstitutional, but were resolved if possible to prevent its enforcement. In the Senate the anti-administration forces were ably led, bent upon embarrassing the Confederate Government and intolerant

Page 6

of opposition. Moreover, they had the moral support of popular sentiment. Timid men bent before the current of public sentiment, and politicians trimmed their sails to catch the prevailing winds. Senator Aycock was neither the one nor the other. He did not sympathize with these views, and came forward as one of the most active leaders in opposition to them. As chairman of a committee to report on that part of the Governor's message, which related to the Conscript Act, he declared that while he lamented the necessity for it, he did "not consider the present to be the proper time or place to decide upon the constitutionality of that measure. . . . Shall the noble-hearted men," referring to those in the army, he exclaimed, "be suffered to call and die in vain, while a man is left at home who can or ought to render aid?" In spite of intense opposition, and in the face of popular sentiment, on every vote taken in the Senate his "name always led the list of those who sought to uphold the Confederate administration, and although that party was in the minority in the Senate as well as in the House, he never flinched in the performance of his full duty to the soldiers in the field and to those who were making such Herculean efforts to achieve Southern Independence."

Benjamin Aycock had no fondness for politics, but, like his son, he considered it the duty of every good citizen to participate in public affairs to the end that good government might be established and maintained; and he neither sought, nor, when called upon by his neighbors, refused to accept public office. But it was as a private citizen that he served his country

Page 7

best. A law-abiding citizen, a good farmer, a God-fearing Christian, he impressed himself strongly on his family and his community. He was, as one of his former pastors tells us, "an excellent member and deacon of the Primitive Baptist Church; and while opening a conference at Aycock's Church in Wilson County (1875), he dropped dead of heart disease, thus falling at his post of duty as did his distinguished son."

Serena Hooks, mother of Charles Brantley Aycock, was a remarkable woman. She possessed intellectual gifts that, in a large degree, made up for her lack of early education. During the years in which her husband's public duties took him away from home, the entire management of the farm and the training of her sons, then at their most impressionable age, fell upon her shoulders. She met her responsibilities with great success. Firm and inflexible in her discipline, she was always kind and affectionate, never in a hurry and never known to lose her temper. In the evenings, during the school term, it was her custom to gather her children around her for an hour or two of study, after which she required them to recite their lessons to her; and although without any education herself, she had no trouble in telling by the expressions of their faces whether or not they knew their lessons. Charles Aycock once saw his mother make her mark when signing a deed; and this incident, as he often declared to his intimate friends, impressed him so forcibly with the failure of the State to do its duty in establishing and maintaining a public school system, that he resolved to devote whatever talents he might possess to procuring for every child born in North Carolina

Page 8

an open schoolhouse, and an opportunity for obtaining a public school education. "His mother," says one who knew her well, "inherited from her mother the strain of Quaker blood which gave her the grave, benignant manner, brevity of speech, gentleness of touch, and tenderness of affection" which she transmitted in so marked a degree to her youngest son. She was noted, too, for her "fidelity to duty, and vigor of mind and body which carried her through a long life of toil and sacrifice, patiently and faithfully borne, and tenderly and lovingly requited, until having accomplished the full measure of her days [1892], she went peacefully to her rest." Governor Aycock bore a strong resemblance to his mother both in character and in features; and to her influence and training he attributed whatever of success he achieved in life.

Benjamin and Serena Aycock had ten children, of whom Charles Brantley was the youngest. The place of his birth was in Nahunta Township, Wayne County, North Carolina. The home in which he was reared "was a quiet one in which affection, order, industry, and frugality were linked with clear thinking, directness of speech, devotion to duty, and deep religious conviction." A pen picture of the community is drawn with such skill and charm by Judge Frank A. Daniels that we reprint it in full.

"The community was wholly agricultural. The owners or their fathers or grandfathers had cleared the lands and brought them into a fine state of cultivation. The crops are usually good because cultivated intelligently and industriously. The largest land-owner

BENJAMIN AYCOCK

Father of Charles Brantley Aycock.

Page 9

was capable of doing as much work as his best hired laborer and took pride in doing it. The farm hand who could keep place with his employer in cotton chopping time was the recipient of warm congratulations. Work was looked upon as the first duty of man, and woe betide the luckless farmer who, forgetting the primal law of life, permitted his cotton to become grassy. If he escaped having his crop auctioned off to the highest bidder at the depot some Saturday evening, in the presence of his neighbors, it was only because he bound himself in the most solemn terms that the next Saturday should find it clean.

"Prosperity smiled upon the community and as wealth accumulated, more land was bought and larger crops were raised. The only investment regarded as wise was the purchase or improvements of land.

"The population was homogeneous. The original settlers were of English stock. The scanty immigration came from the same source, and was confined to the occasional arrival of an individual or family from a neighboring county. They were a strong and vigorous people, independent, industrious and religious. They had not much of the culture derived from books, but they had a culture which cannot always be obtained from books. They were well informed on political questions, kept in touch with the great movements of the day, advocated and practised, as opportunity permitted, the education of their children, exhibited a patriotic interest in the welfare of the country, and when soldiers were needed gave their best and bravest to die for their principles.

"They were an undemonstrative people. Simplicity

Page 10

of life characterized them. 'Deeds, not words,' might have been written as their motto. They strove to be accurate and literal in their statements. Exaggeration or hyperbole was foreign to them. A flood was to them a tolerably heavy rain; an enormous crop, a fair yield; a great speech, a good talk. If one was ill, he was 'not very well,' and if he was well, he frequently described himself as 'just up' or 'so as to be about.'

"They had a courage of a high order, but never vaunted it. It was of the quiet sort, that makes itself felt when occasion demands. A typical Nahunta man, whose company was charging the enemy in one of the battles of the War Between the States, engrossed in the business in hand, went his steady gait in the direction of the foe, under a storm of shot, when, not hearing his comrades, he turned and looked to see what had become of them, and found they had stopped a hundred yards or more behind him. He yelled to them at the top of his voice, 'Fellows, why don't you come on?' and stood his ground until they came. He was never able to see the point of the compliment his Captain paid him in camp that night; his only feeling seemed to be one of good-humored contempt for the 'fellows' who wouldn't 'come on.'

"The hospitality of the community was proverbial. It was kind and unostentatious, but open-handed. It was impossible to escape the kindly, cordial importunity extended on all sides, and it was no infrequent thing for twenty-five guests to sit down to dinner in one of the modest homes of that community.

"It was expected, of course, that every man should

Page 11

take care of himself and his family, and in the rare instances in which this expectation was disappointed, the thriftless or lazy wight soon had it borne in upon him in some indefinable way, that his further stay was not desirable, and ere long took his departure. The tricky and dishonest felt the frown of public condemnation, and could not thrive in that pure atmosphere.

"The hand of charity was always extended to the unfortunate, but only to the deserving. Indiscriminate giving was felt to be a wrong to the recipient as well as to the community.

"When sickness or misfortune came the spirit of mutual helpfulness was a guaranty that no harm should come to the afflicted one, and the neighbors volunteered to do the plowing, chop the cotton, or gather the crop as required.

"There was in all classes a deep-seated regard for law and order and a strong attachment to democratic government. No more democratic community, both in principle and in practice, could be found among civilized men, and coupled with this was the spirit of instant and determined opposition to misrule or oppression, which is always found where democratic principles dominate.

"The virtues of this community are traceable in great part to the strong hold of religion upon the people. The Primitive Baptist faith, strongly Calvinistic, had many adherents, and was the controlling factor. Under its influence men and women, strong in faith and character, grew up, led public sentiment, and gave tone to moral and social life."

Page 12

Multiplied by itself a sufficient number of times, Nahunta becomes North Carolina; and in this fact we find the secret of the hold that Charles B. Aycock was able to secure and retain upon the people of the State. The spirit of Nahunta was the spirit of North Carolina, and because he understood the one, he understood the other. That spirit thoroughly permeated the nature of young Aycock, and being a "typical Nahunta boy," he became by a natural process of development a typical North Carolina man. The simplicity of character, the independence of thought, the homely virtues of the people among whom he was born and reared, reached their fullest development in him. No man understood more clearly than himself the influence which his early environment had in moulding his character, in forming his habits of thought, in shaping his attitude generally toward life.

The feeling of local attachment was strongly developed in him. While Governor of the State he declared to a large audience in the State of Maine: "I love my home town better than any other town in Wayne County; I love Wayne County better than any other county in North Carolina, North Carolina better than any other State in the Union, the United States better than any other country in the world, and," he added half jestingly, half seriously, "I love this world better than the next." The same thought found fuller expression shortly before his death, in his address on Robert E. Lee. "The love of home, of family, of neighborhood, of county, of State, predominated in him. The elemental foundation of all

Page 13

free government is found in this vital fact. There can never be a free people save those who love and serve those closest to them first, and those farthest away afterward. The Gospel must be preached to all the world, but its preaching must begin at Jerusalem. It never could have begun anywhere else, and if it had, it never would have gone anywhere else." There is nothing new or original in this sentiment: thousands of others before him had said the same thing. But Charles B. Aycock believed it, and the people of North Carolina knew that it was the mainspring of his life. During the campaign of 1900, after he had spoken to an immense gathering at Goldsboro, Mr. Josephus Daniels wrote to his paper, The News and Observer:

"These Wayne County people believe so thoroughly in Aycock that they are not astonished at any feat he has accomplished. I told one to-day that in Catawba County he made the greatest speech of his life to 5,000 people. What do you think his reply was? 'I reckon Charles made a right good speech in Catawba, but I just know it couldn't hold a light to that speech he made in Great Swamp [a township in Wayne County] in 1896.' Speaking to an honest old-time Democrat, I said, 'Aycock made a powerful speech in Wake County yesterday,' 'I reckon so,' he replied, but he never can speak half as well away from home as he can at Nahunta or Pikeville. There he beats all creation."

And the "old-time Democrat" was right. It was the Nahunta boy's soul burning with desire to serve

Page 14

Nahunta that gave him his first inspiration: and as time and opportunity broadened his field of vision and of service all of North Carolina became to him as was Nahunta.

Born a little more than a year before the outbreak of the Civil War, Charles Aycock was nearly six years old at its close; and he grew to manhood during the period of Reconstruction. He was, therefore, of an age to receive vivid impressions of the events of both periods, yet not old enough to imbibe the bitterness to which they gave birth. He made frequent and effective use of his impressions of the conditions under which he passed his boyhood days in his campaign speeches, and before juries which, taken altogether, reveal the vividness of his recollections of those days. He remembered, he said, "the closing years of that great internecine strife which swept over my [his] country like a besom of destruction"; and he recalled how his own elder brothers, and other Confederate soldiers, returned from the army "weary, worn and sorrowful, to find their farms gone to ruin, their fences down, their ditches filled, their stock slaughtered, in too many instances their houses burned." "There was neither food nor raiment, and those who had in the past labored for them were free, and were enjoying their new freedom with a license which imperiled life and property, and their fields were gone to waste. They were without capital and without material with which to begin the struggle of life. They had neither teams nor agricultural implements with which to begin the work." "Mourning was everywhere in the land. Universal poverty, actual scarcity, real suffering,

Page 15

genuine want were in the State." But worst of all was the hatred which had been engendered, not only between North and South, but even among neighbors and families of the same community. He remembered "how the people hated Abe Lincoln, and how the Yankee folk hated Jeff Davis. Their pictures appeared in all the papers, they were caricatured and cartooned from one end of the country to the other. Abe Lincoln's face lent itself to the facile pen of the cartoonist to make it look hideous, while Davis's face was easy to be made monstrous. And they paraded them over the country, to the gratification of the respective partisans of either side." It was a time "when reason had lost its base, when men almost forgot God, when they became familiar with death and blood and slaughter, and lay down with hatred in their souls."

It is not necessary to describe the political conditions that prevailed in North Carolina during the era of Reconstruction: that task belongs to the general historian. Yet after 1865 there never was a moment of his life when Aycock was not under the direct influence of those conditions, for they cut deep the channels along which flowed the current of his life, and which determined the course of his public career. In 1868, the period of Congressional Reconstruction began, and Wayne County, together with the other counties of the East, passed into the control of the Carpet-baggers and their negro allies. Their brief rule was characterized by inefficiency, extravagance, violence, and unblushing corruption. On the part of the native whites, political contests assumed all the

Page 16

seriousness of a desperate struggle for the preservation of life, liberty, and property.

Too young to take any part in this struggle, Charles Aycock was old enough to be profoundly impressed, without clearly understanding it all, by what went on around him. His father's house became a favorite rendezvous for the Nahunta farmers, who, of a summer's evening, gathered on his broad piazza and discussed politics far into the night. Frequently their discussions were carried on in the hearing of an unknown auditor; for though Charles was always early ordered off to bed, he sometimes slipped out of the back window in his night clothes, crept silently around the house, and hiding under the front porch steps, lay there as quiet as a mouse, eagerly listening to the words of his elders.

It was at this period, too, that the lad heard his first political discussion when John W. Dunham, a Democrat, met James Wiggins, a Republican, in joint debate at Nahunta. Dunham was a member of the Wilson bar, an educated man, with a reputation as an experienced and vigorous campaigner. His opponent, familiarly known as "Jimmie" Wiggins, was an illiterate man, without respect for the King's English, awkward in his manner, and grotesque in his delivery. Charles Aycock, boylike, secured a seat immediately under the speakers' stand. Dunham opened the debate in his usual good style, but his speech made no impression on young Aycock. But the moment Wiggins began to speak, the boy riveted his eyes upon him, followed every gesture, and caught every word. He missed nothing. No awkward movement, no

SERENA HOOKS AYCOCK

Mother of Charles Brantley Aycock.

Page 17

slang expression, no intonation of voice, no facial contortion, escaped his attention, and upon his return home he astonished his family by repeating the speech almost verbatim. For many a day after that memorable occasion it was a favorite amusement in that community to place young Aycock on a goods-box in the midst of an appreciative audience, who cheered and roared heartily as he repeated the words and mimicked the tones and gestures of "Jimmie" Wiggins.

Civil War and Reconstruction had destroyed the public school system which Calvin H. Wiley had built up in North Carolina, and young Aycock was forced to pursue his education in a haphazard sort of way at such private schools as chanced to be conducted within his reach. The first of these schools was at Nahunta, where the people of the community, by uniting their small means, had employed a teacher. Here Charles Aycock, under the chaperonage of his six older brothers, first entered school. "It was an inspiring spectacle," says one who frequently witnessed it, "to see these seven fine fellows on their way from the farm to the school. Charles was then about eight years of age, and was the pet of the family. It was no unusual sight to see Frank, the oldest, trotting down the dusty road with Charles, the youngest, on his big broad shoulders -- 'Big Sandy' and 'Little Sandy,' as Charles called his brother and himself. They carried their dinner in one tin bucket, and as all were hale and hearty young men and boys, it can easily be imagined that it required an ample one to supply their demands."

From Nahunta to Wilson, thence to Kinston, the ambitious lad pursued his search for an education.

Page 18

At Wilson he entered the Wilson Collegiate Institute, then conducted by Elder Sylvester Hassell, who declares that in young Aycock he had "a bright and exemplary pupil." One of his schoolmates remembers that the "teachers supposed Charles Aycock had not had the best preparation and accordingly put him in classes with younger boys than himself; but he soon showed that they had made a mistake, and they promoted him to classes of boys of his own age and older, where he maintained first place in many studies. He was particularly strong in Latin and grammar and English. There was no boy in the school who could touch him in these three studies. He could translate English into Latin with a facility that astounded the other boys in the school, and he seemed not only to know Latin grammar by heart but was able to apply it with accuracy and quickness; the verbs seemed to be at his tongue's end. He was not then, or at the University, strong in mathematics."

Declamation and debating, to which every Friday afternoon was devoted, formed an important feature in Mr. Hassell's scheme of education, and in these young Aycock excelled. "His voice," we are told by one of his youthful rivals, "was not melodious, and he was rather awkward in his movements, but when he rose to speak, every person within reach of his voice listened until his conclusion." His earnestness, sincerity, and directness in debate compelled attention. His schoolmates recall that at the declamations on Friday afternoons, when declaiming some of the old masterpieces with which all the schoolboys were familiar, he seemed to make them his own, and to be

Page 19

able to get hold of his audience as well as if he were making a speech that he had composed, suitable for the occasion. The teachers and children of other schoolrooms would throng the hall to hear him. It was in the moot court of the debating society, associated with his future law partner, Hon. Frank A. Daniels, now Judge of the Superior Court, and against Mr. Rodolph Duffy, afterward solicitor of the Sixth Judicial District, that the future advocate defended and won his first murder case.

"I recall," says Mr. Josephus Daniels, "that when Aycock was at school in Wilson he did not board in the school building, but two miles in the country, and walked to school every day, bringing his dinner with him and often in the noon hour, after eating, he devoted himself to study." But let it not be supposed that "studying after eating" occupied his undivided attention during the noon hour. Young Aycock was a strong, healthy lad, of sociable instincts, fond of sports, and at times he certainly did, by an exercise of strong will power, tear himself away from his books and join the other fellows in their games. Besides, among his fellow-pupils there were two sisters, Misses Varina and Cora Woodard, who certainly taught him some lessons which he did not learn from books, either before or after eating.

At Kinston, young Aycock had the good fortune to come under the influence of a masterful teacher, Rev. Joseph H. Foy, who quickly recognized his pupil's superior abilities, and took great pride in directing their development. He encouraged the boy in his ambition, fired his zeal for learning, and awoke in him

Page 20

a spirit of self-confidence. Governor Aycock never forgot, nor failed to acknowledge, the interest which this instructor took in him. Under Mr. Foy his preparation for college was completed. The family all recognized that he was no ordinary boy, and believing that he possessed talents which, with proper training, would raise him to a position of note in the State, determined that every sacrifice should be made to send him to the State University and to educate him for the bar.

Page 21

CHAPTER II

FROM FARM BOY TO UNIVERSITY LEADER

YOUNG AYCOCK entered the University of North Carolina in the fall of 1877. His appearance made a distinct impression upon his fellow-students, and many of them "recall vividly" the strong, sturdy-looking country boy, upon his first touch with a world somewhat larger than his own neighborhood. Says one of them, Hon. Francis D. Winston:

"I recall vividly my first meeting with Charles B. Aycock. He was sitting in a hack in front of Watson's Hotel on his arrival in Chapel Hill to enter the State University. A crowd of Sophomores was present to greet the newcomers with yells and cheers and other evidences of fraternal solicitude and scholarly welcome. Aycock was yet a boy in appearance and bore about him the simplicity and naturalness of one who has just left the plow handles on his father's farm. He looked as modest as a girl, but unaffected and self-reliant. He stepped out of the hack with as much composure and as little self-consciousness as if he were alighting from a load of wood at his own home. The boys yelled and cheered. I stepped forward, grasped his hand, looked into the clear, honest blue eyes of as true a man as ever lived, and felt for him the thrill of friendship that is akin to love."

Page 22

Charles Aycock entered the University at a transition period in its life, and in the life of the State. The old University had passed into history together with the Civil War and Reconstruction; the new University had its face turned toward the future.

"There was no better place, I think," says Dr. Edwin A. Alderman, "for the making of leaders in the world, than Chapel Hill in the late seventies. The note of life was simple, rugged, almost primitive. Our young hearts, aflame with the impulses of youth, were quietly conscious of the vicissitudes and sufferings through which our fathers had just passed. 'The Conquered Banner' and the mournful threnodies of Father Ryan were yielding place to songs of hope. A heroic tradition pervaded the place, while hope and struggle, rather than despair or repining, shone in the purpose of the resolute men who were rebuilding the famous old school.

"All of us were poor boys. Those who came from the towns looked, perhaps, a trifle more modish to the inexperienced eye, but they were just as poor as their country fellows, and had come out of just such simple homes of self-denial and self-sacrifice. The unconscious discipline and tutelage of defeat and fortitude and self-restraint, had cradled us all. We had all seen in the faces of our patient mothers and grim fathers something that we knew, if we could not express, was not despair, and somehow, life seemed very grand and duty easy and opportunity precious."

New problems in politics, in education, in scholarship, in industry were beginning to press themselves upon the attention of the Commonwealth, and among

Page 23

Aycock's fellow students were not a few of those who have since led the way to their solution. He strove for college honors against such men as Charles Duncan McIver, Edwin A. Alderman, James Y. Joyner, Robert P. Pell, M. C. S. Noble, Henry Horace Williams; against Francis D. Winston, Robert W. Winston, Rufus A. Doughton, Locke Craig, Frank A. Daniels, Charles R. Thomas, James S. Manning, and Robert Strange. It was no slight achievement for the raw country boy fresh from his Nahunta farm even to hold his own with these students: to become, as Aycock quickly did, an acknowledged leader among them marked him as no common youth.

Aycock entered the Sophomore class. It was his wish to complete the course required for graduation in two years, but the upper classmen protested, and the Faculty refused its permission. He had a strong, vigorous mind and a tenacious memory, and easily mastered most subjects. His general record, therefore, was good, but in science and mathematics his marks fell below the average. His term standing in mathematics once falling below the grade required for graduation, he resolved not to continue his course for his degree but to pass at once into the law school. But his friends sought earnestly to dissuade him from this course, and finally induced him to take a second examination, which, as he himself used to say, he succeeded in passing "by main strength and awkwardness." But in Latin, English, Political Economy, Logic, and Moral Philosophy he took high rank, becoming particularly distinguished for his Latin and

Page 24

English composition. His talent for the latter found a field for development on the editorial staff of the University Magazine, and in the debates and essays which formed the work of the Philanthropic Literary Society. He also edited, for a while, the Chapel Hill Ledger, a local news weekly. In his Senior year he was awarded the William Bingham Essayist's Medal; and at Commencement of his graduation, 1880, he won the Willie P. Mangum Medal for oratory, speaking on "The Philosophy of the History of New England Morals." These distinctions meant, of course, that he was the best writer and the best speaker in his class. During his Senior year, in addition to his regular college course, he read law under Dr. Kemp P. Battle, then president of the University. In spite of his strenuous classroom work, Aycock found time for a wide range of reading. He had the capacity to master books, and while at the University developed a strong love of literature which survived the shock of legal and political contests, and remained until the day of his death, one of his chief sources of entertainment and inspiration.

At that time all academic students were required to become members of one of the two literary societies -- the Philanthropic and the Dialectic -- whose history is almost co-terminous with the history of the University itself, and in which not a few of America's most eminent statesmen received their training in debate and parliamentary practice. Aycock became a "Phi," and his fellow members still tell with great glee, how on the very night of his initiation he signalized his first appearance by "cleaning up" every debater

AYCOCK AS A YOUNG MAN

Aycock is supposed to have been twenty years old at the time this picture was taken -- a student of the University.

Page 25

on the floor. One of them relates the incident as follows:

"Robert W. Winston was one of the debaters for that night. After the regular debaters had finished, Judge Winston called upon the new comer, Charles B. Aycock, for a speech. The call was good natured and evidently intended to embarrass the country boy who had just entered the University. Aycock arose and began speaking. We all took notice at once, and the boys realized that they were in the presence of the most brilliant speaker in the college. He cleaned up every fellow who had gone before, and created great merriment by declaring that the illogical contentions of the debaters on the other side reminded him of the 'fellow who was looking for a black cat in a dark cellar, on a dark night, with no light, when the cat was not there.' "

All student activities, social, political, and literary were conducted through the societies, and it was in them, rather than in the classrooms that the ambitious student strove for leadership. Those who led the societies, led the University. The work of the society was Aycock's natural element, and he passed quickly, almost immediately into leadership. He loved the stimulating clash of debate, the thrill and excitement of battle -- to the college student quite as real and quite as serious as were the mightier conflicts of later days to the party leader. In college politics, as in the conflicts of state and national affairs, he struck and received swift, hard blows, but it is the testimony of all that he fought a clean, manly fight. His blows left no sting, nor did he, himself, harbor any bitterness

Page 26

of spirit. "Once I saw him," says Professor Williams, "in a royal battle for an honor in the Phi Society. He detected some ugly practice. Instantly he withdrew from the contest. Then he made the finest appeal for clean methods and high ideals I ever heard."

On another occasion he chanced to be for the time in opposition to an intimate friend, his junior in age, and his inferior in physical strength. Under the impulse of a youthful resentment at something Aycock had said, the other sprang up, exclaiming, "The gentleman from Wayne has stated what is false; I repeat, sir, what is false." For a moment the atmosphere was charged with electricity, and all awaited with apprehension the expected outburst; but Aycock, with complete self-control calmly arose and asked for permission to interrupt the speaker. "I shall never forget Aycock's words," declares the latter, "as he quietly said: 'The gentleman has used language on this floor which he well knows he would not have used but for his size and the relations heretofore existing between us.' I was, of course, overwhelmed with mortification, and replied: 'It does not matter about my size, but it does make a very great deal of difference about our relations. I spoke without thinking or realizing what I was saying. I retract the language and ask the gentleman's pardon,' and sat down in confusion. I had hardly taken my seat before Aycock had crossed the hall, dropped into the seat next to me, and putting his arms around my shoulders, said: 'It's all right, Jim. Don't let this worry you. I knew you didn't mean it, and it shan't affect our friendship.' "

Page 27

No incident of Aycock's college career shows the position of leadership which he so quickly attained more clearly than his election as chief marshal in his first year. The chief marshalship was the most coveted social honor of student life. The office alternated from year to year between the two societies. In Aycock's first year it came to the Phi Society, and early in January, 1878, Frank Wood, of Edenton, was chosen, but a few days before Commencement he resigned in order to go to the Paris Exposition. Naturally the sub-marshals expected that one of their number would be promoted to the vacancy, and they were keenly disappointed when the choice of the society fell upon Neal Archibald McLean, a popular law-student. The sub-marshals and their friends promptly protested to the Faculty against McLean's election on the ground that being a law-student he was ineligible for academic honors. The protest was argued at great length and with much warmth, and the Faculty, after deliberating all day, decided against McLean. This decision resulted in a contest long remembered by those who participated in it, one of whom, Prof. M. C. S. Noble, gives the following account of it:

"McLean had not been elected through any bitter party fight, but simply because he was a popular fellow, and when the Faculty decided against him there was much indignation that the will of the society had been thwarted and that McLean, vice-president of the society, had been declared ineligible for a Commencement honor. At once McLean's friends determined not to permit the election of any of the sub-marshals

Page 28

who had led the fight against him. Accordingly, a party was formed determined to have no Faculty interference with the prerogatives of the society, and all over the campus, groups of students gathered to indulge in earnest and heated discussions. A caucus of the new party's managers was held, and Aycock, who had not wanted the honor, was made to take it because he, too, like McLean, was a popular fellow and had been an indefatigable fighter for McLean from the moment the contest started. The machine of the new party was composed of those who were in the caucus, and the faithful on the outside were told to wait for the nominating speech to learn the name of the candidate agreed upon. When the society met and received the report of the Faculty, McLean tendered his resignation, after which the President called for nominations. For a few minutes there was an intense stillness, each side waiting for the other to move first. Then a member rose and nominated one of the sub-marshals. The President asked if there were other nominations, and 'Neal Arch' McLean, addressing the chair, spoke plainly his opinion of the Faculty's action, thanked his friends for their support of him, and then with a voice full of emotion said, 'There is one here who can serve you better than I, and I, therefore, nominate Charles B. Aycock.' The opposition was dumfounded, the vote was taken, and Aycock was elected. A student rushing out of the hall downstairs to the campus where the Di's were waiting to hear the news, yelled 'Aycock!' which the crowd received with triumphant shouts and cheers, while the college bell chimed in and lent its voice to the celebration."

OLD SOUTH BUILDING, STATE UNIVERSITY

Aycock roomed on the lower floor. The two windows seen in the pitcure immediately to the left of the well were in his room and indicate its position.

Page 29

"At Commencement in June, following his election," relates Judge Daniels, "whether by the procurement of some humorous friend or some jealous rival, or by one of those accidents which defy explanation, as he led the academic procession, arrayed in all the glory of Chief Marshal, the band struck up the then popular tune, 'See the Mighty Host Advancing, Satan leading On,' much to the amusement of his friends and somewhat to his own discomfort."

Thus within a single year Aycock had become the leader of the largest and most influential group of students in the University. His leadership had come not through scholarship, though he was by no means deficient in scholarship, but through the larger and richer life of the campus, where the college man's capacity for leadership is tested and developed. College-life is nothing less than world-life in miniature, and he who would lead the one, as well as he who would lead the other, must understand men rather than books. Professor Williams describes this college life at the University of North Carolina as "the long walk after supper when two men talk together of their hopes, their principles, their visions, their deeper selves. It is the hour of communion in the old room after midnight, when the day's work is done, the light burns low, and soul speaks to soul. It is the banter and raillery and fun of the crowd on the steps of the building for an hour after supper. It is the struggle on the campus for leadership. It is the rigid and swift judgment of the student body. It is the impartial application of standards. The judgments of this campus are to me the finest in the world. Hypocrisy

Page 30

does not long live here. The writ of value is honesty. In this sphere Aycock found his place. He saw here the food upon which right manhood must feed. He opened wide his mind and spirit. He loved it with all the depth of his great nature." He studied it, he conquered it, and he led it as he willed. It is needless to add that it was this training which fitted him to be the leader of his people in the great crises of 1898 and 1900.

It is evident that Charles Aycock made a deep and lasting impression on his fellow students and on the University. We should leave this chapter of his life incomplete if we failed to point out, though ever so briefly, the impression which the University made upon him. The University of North Carolina was established to train men for the service of the State. The true "University man" understands this, and accepts his education at her hands knowing that, if he be true to her teaching, he is under the highest sort of obligation to use the increased power which he receives through her training not for his own advancement, but for the good of the Commonwealth. When the State requires his service, he knows that he is expected to give it freely and cheerfully, regardless of any personal losses and sacrifices. Such has always been her teaching; and such has always been the spirit of her sons.

No man understood this better than Charles B. Aycock. He knew that out of the old University of ante-bellum days had come such men as Murphey and Wiley and Battle, and many others who had heard the call of the State and had never failed to respond.

Page 31

Standing upon the day of his graduation, as we have already said, at a transition period in the life of the University and of the State, he, too, heard a call for a new and distinct service. McIver heard it, and Alderman, and Joyner, and Noble. Each responded after his own fashion, but all had the same object in view. Shortly before his graduation Aycock caused to be debated in the Phi Society this query, "Ought The Public School System of North Carolina to be Abolished?" while the same evening he himself, as Senior orator, discussed in an elaborate oration, "North Carolina's Deficiency and Our Duty." He had caught a vision of an old Commonwealth re-made and revivified through universal education, and he went forth from the University pledged to give to that cause the best services of his life.

Page 32

CHAPTER III

THE FOUNDATIONS ON WHICH AYCOCK BUILT

HIS CHARACTER

WE SHALL not attempt in this volume to follow an exact chronological order. The most significant thing about a man is not a record of dates and deeds, but the silent development of his character. It is much as Carlyle says -- that "the Event, the thing which can be spoken of and recorded," is in most cases a disruption, a break, while the real growth has gone on in silence: as "the oak grows silently in the forest a thousand years" with no "event" to note until in the thousandth year it falls.

Before proceeding with the events of Aycock's life, therefore, let us pause to consider the foundations on which he built his character. That these foundations were laid before he completed his college course and before he began his career at the bar, we are assured; and it is necessary to understand them in order to understand the man. However, in attempting this estimate we shall have to select significant manifestations of his character from many periods of his career.

There are several single sentences that seem to give snapshots, as it were, of Aycock. We have already quoted some of them: Bishop Kilgo's saying: "He lived out his whole life under the despotism of duty," Archibald

Page 33

Johnson's: "He won great love because he was a great lover," and Elder Gold's: "He had the simplicity of sincerity, and the sincerity of simplicity."

Yet it often happens that in some moment of self-revelation a man unconsciously utters the best characterization of himself. So it seems to us that Aycock, but ten days before the end, and while the death-angel already beckoned him from a task he was never to finish, gave perhaps the best one-sentence characterization of himself when he read his friends from the unfinished manuscript of the speech he had prepared for delivery on April 12th: "For I am a plain and simple man who loves his friends, and has never been hated enough by any man to make him hate again in return."

Love -- simplicity. These were indeed the ruling principles of Aycock's life. It is hard to realize that a man could have been the leader in the mighty campaigns of 1898 and 1900, when the primal passions of race-feeling were stirred to white heat, and could also have dared all uncharitableness in four years of strenuous devotion to duty as Governor, and yet not have made an enemy. But so it was. And when in the sunshine of the April morning a sorrowing State welcomed back his body to the soil he loved, there were none who spoke him more fair in death than those whom he had met as rivals in fierce debate. Judge Jeter C. Pritchard uttered the sentiment of men of all parties when he wrote: "He was incapable of anything small or mean, above all low suspicion, bearing no malice in his heart. At times he was called upon to say and do things that for the moment were unpopular,

Page 34

but he had the moral courage and the manhood to do right regardless of consequences."

Perhaps no other man in Southern history, except Aycock's great ideal, General Lee, has ever fought any great fight with as little bitterness as Aycock fought his. The writer has heard Capt. E. E. Lovell, of Watauga, tell of hearing General Lee give orders in battle: "We must attack those people at yonder point." It was simply "those people": never "the Yankees," or "the enemy," but "those people."

"Hate the sin, but love the sinner," is an old theological doctrine; and Aycock, denouncing Republicanism, yet liked Republicans. In fact, he was most effective as a speaker because while powerfully arraigning what he regarded as a bad cause he would persuade and convince its advocates rather than anger them. In a letter now before us, a friend tells of hearing Aycock in Goldsboro in 1898, when the bitterness of that memorable campaign was at its height. He was interrupted in a flight of masterly eloquence by some one who called out, "Give it to Butler!" Says our correspondent: "He stopped his speech, and from the grandest oratory, descended to that gentle, persuasive tone peculiar to him, and replied in the following words: 'No, my friend, in this our supreme hour of victory, I will abuse no man!'"

This was characteristic of Aycock -- not that he did not speak with terrific earnestness and force, and with powerful conviction, but that he always spoke for something, not against something. He was speaking in 1898 not against the negro, but for the white man -- for the white man's inherent right to rule as a condition

Page 35

necessary to the welfare of both races. "I like a man who is for somebody, who is for something," he wrote but a few months before he died, "not a man who is against somebody, or against something." In other words, he believed in a life of positiveness, not of negation; of love, not of hate. In Doctor van Dyke's fine phrase, he "was governed by his admirations, not by his disgusts." And very early in his career he found in Tennyson's "Maud," the poem which he loved from his youth up, and which he knew almost by heart, an expression which may be regarded as the keynote of his endeavors:

"It is better to fight for the good than to rail at the ill."

Aycock believed as strongly as anybody in remedying the evils of trusts, but it was not because he was against trusts, but because he was for justice. No one was more earnestly opposed to the freight discriminations against the State, but it was not that he was against the railroads but for equality. No North Carolinian ever more powerfully arraigned the protective tariff, but this was not that he was against capital but for right. His tendencies were constructive, not destructive; positive, not negative. He would crowd out evil by supplanting it with good -- just as in boyhood he kept a field from growing weeds by sowing wheat on it. The Biblical injunction, "Whatsoever things are pure, whatsoever things are lovely; think on these things," -- rather than on their opposites -- was never lost on him. It was because of this fact that Aycock's nature was ever sweet, wholesome and serene. Emerson observed a long time ago: "It is easy in the

Page 36

world to live after the world's opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude." This is what Aycock did. When criticism of his "universal education" policy was fiercest, and it was said, "Aycock couldn't even be elected a constable in Wayne County," he sat in the Governor's office, smoked his long-stem pipe and viewed the situation with composure indeed, but not with a mere stoical, martyr-like conviction that he had done his duty as he saw it and must take the consequences. That sort of feeling -- which may put iron into a man's blood but will certainly rob it of its warmth -- was not Aycock's spirit at all. He not only knew that he had done his duty and that all the powers of earth could not make him swerve from it, but he had a perfect trust in the people: absolute confidence that they would sooner or later come to recognize not only the integrity of his purpose but the wisdom of his policy. And in this spirit, in the very middle of his administration, he concluded his message to the Legislature of 1903 with these words: "There is but one way to serve the people well, and that is to do the right thing, trusting them, as they may ever be trusted, to approve the things which count for the betterment of the State."

Serena was Aycock's mother's name, and he inherited from her Quaker blood something of the fine quality which her name suggested. "I never knowingly read any article about me written in a spirit of either praise or blame," he said to the writer but a few months before his death. "If it's praise, it may unduly excite my vanity; if blame, it might arouse some animosity."

Page 37

In harmony with this statement is a story of Dr. J. Y. Joyner's. Disagreeing with Aycock, about a matter in which they were both interested, he finally sent Aycock a letter written in some heat. Regretting this on more mature reflection, he wrote in apology and received substantially this reply: "Your first letter was received, but I suspected it was a warm number, and it has never been opened. I am returning it to you." Rev. Livingston Johnson also gives this incident: "Just before he retired as Governor, I wrote him congratulating him upon his successful administration, and commending especially his constructive interest in education. He replied promptly, thanking me for the letter, and said that he turned over all such letters to his daughter who wished to preserve them, but the ones bearing adverse criticism he destroyed and forgot."

This may seem to have little to do with our initial declaration regarding love and simplicity -- or better, love and sincerity -- as the dominating qualities of Aycock's life; but in fact, it has much. It was because he loved and trusted his fellows and believed in them that he had this serene confidence in their rightness, and kept his faith that the good and wholesome things are the significant things and the only things which one should regard or remember. In the most eloquent sermon the writer ever heard from a North Carolina minister, Bishop Kilgo pointed out that the Almighty's estimate of a man is the sublimest moral height the man ever reaches -- just as Barrie's "Little Minister" insists that, "To see the best is to see most clearly," and Browning's "Abt Vogler" declares that all good shall perish "with, for evil, so much good more." Such

Page 38

was Governor Aycock's doctrine. Judge Hoke has referred to him as the finest exemplification of Lowell's sentiment:

"Be noble! And the nobleness that lies

In other men sleeping but never dead,

Will rise in majesty to meet thine own."

He maintained that one should believe in the best in people. "You can't help a child do better by reminding him of mistakes and shortcomings," he would say, "point out to him the possibilities and rewards of worthy conduct in the future." Even one's errors and failures were not valueless to a sincerely aspiring man, he insisted; and that

"Men may rise on stepping stones

Of their dead selves to higher things,"

was one of his most frequently used Tennysonian quotations.

It should not be assumed, however, that Aycock was easily deceived by men. He was not. On the contrary, he had something of a woman's intuitive promptness in "sizing up" any one to whom he was introduced, and his judgment was seldom in error. He simply preferred in all things to emphasize the good he saw rather than the bad.

Nor should any one suppose that Aycock was ever of the flattering, back-slapping, indiscriminately effusive type of politician. No man was freer from such faults. In fact, if he had to choose between abusing a man a little to his face, or paying compliments he did not believe deserved, he would undoubtedly have chosen

Page 39

to abuse him a little, because flattery would have implied insincerity, which fault of all faults he was freest from. He loved his friends, but he respected Emerson's doctrine that one "should never by word or look overstep one's real sympathy." He knew how to express his regard for any one he cared for, but he did this in such a way as never to appear effusive. As some one said just after his death: "Charlie could let you know that he loved you without ever having to say so in words." If, therefore, one should accept Judge Pritchard's estimate, "As a friend I knew him best; there was no truer, sweeter, more affectionate man," it should always be with the further understanding that Aycock was never, to use his own excellent phrase, "too sweet to be wholesome." In fact, I think he should hardly have liked for any one to accuse him of having "a sweet nature," unless some recognition of his robust manliness were added. Virile, courageous, and almost literally "six foot A1 of man, clean grit and human natur'," he impressed many others as he did Prof. J. I. Foust who says: "He was without doubt the bravest man with whom I have ever come into contact."

With all Aycock's high ideals, therefore, and his hatred of everything mean and sordid -- if, indeed, one should not even here use the positive term and rather say his love of everything high and worthy -- the writer never heard him utter a word that sounded like "preaching." He hated cant as much as he hated viciousness, and hypocrisy as much as he hated meanness. In extreme cases he might openly rebuke the guilty--as when some classmates used unfair methods in an election at Chapel Hill, or when his soul flamed out in

Page 40

hot indignation at some lewd fellows on a train who told unclean stories in the presence of a little boy -- but such instances were rare. He preferred rather to do as General Lee did, of whom he wrote:

"Lee did not criticise his people; he did not reprove them; he did not even tell them what the best things in life were. He just simply lived among them the very best things that there are in life. He was himself the best thing, and in this way he has done more to lift us up than any amount of speech or writing can ever do."