The Slave: or Memoirs of Archy Moore.

Vol. I:

Electronic Edition.

Hildreth, Richard, 1807-1865

Funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Elizabeth Wright and Natalia Smith

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc., Lee Ann Morawski and Natalia Smith

First edition, 2001

ca. 300K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2001.

Source Description:

(title page) The Slave: or Memoirs of Archy Moore. Vol.

I

[1], 170 p.

BOSTON:

JOHN H. EASTBURN, PRINTER.

1836.

Call number T. R. 813.3H644s, v.1v (McCormick Library

of Special Collections, Northwestern University)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been entered using double-keying and verified against the original.

The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

All footnotes are inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

Languages Used:

- English

LC Subject Headings:

- Fugitive slaves -- Virginia -- Fiction.

- Plantation life -- Virginia -- Fiction.

- Slavery -- United States -- Fiction.

- Slavery -- Virginia -- Fiction.

- Slaves -- Virginia -- Fiction.

Revision History:

- 2001-10-23,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2001-06-26,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2001-05-09,

Lee Ann Morawski

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2001-05-03,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

- finished transcribing the text.

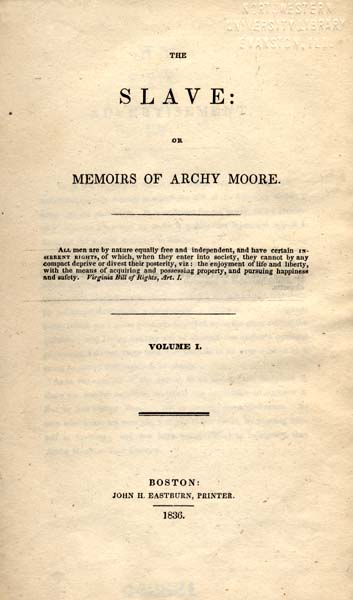

[Title Page Image]

[Title Page Verso Image]

THE

SLAVE:

OR

MEMOIRS OF ARCHY MOORE.

ALL men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain. INHERENT RIGHTS, of which, when they enter into society, they cannot by any compact deprive or divest their posterity, viz: the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing happiness and safety. Virginia Bill of Rights, Art. I.

VOLUME I.

BOSTON:

JOHN H. EASTBURN, PRINTER.

1836.

Page verso

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1836, by JOHN

H. EASTBURN, in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of Massachusetts.

Page i

ADVERTISEMENT.

IT is unnecessary to detain the reader, with a narrative of the somewhat singular manner in which the MS. of the following Memoirs came into my possession. It is sufficient for me to say, that I received it, with an injunction to make it public--an injunction which I have not felt myself at liberty to disobey.

I would not be understood, however, as implicitly adopting all the author's feelings and sentiments; for it must be confessed that he sometimes expresses himself with a force and a freedom, which by many will be thought extravagant. Yet, if I am not greatly mistaken, he preserves throughout, a moderation, a calmness, and a magnanimity, which have never yet been displayed upon the other side of the question; and laying entirely out of account the author's personal grievances, I do not know how it is possible to be over zealous in a cause so just as that in which he pleads.

As to the conduct of the author, as he has himself described it, there are several occasions on which it is impossible to approve it. But he has written Memoirs, not an apology nor a vindication. No man who writes his own life, will gain much credit, by painting himself as faultless; and few have better claims to indulgence than Archy Moore.--THE EDITOR.

Page 1

MEMOIRS.

CHAPTER I.

YE who would know what evils man can inflict upon his fellow without reluctance, hesitation, or regret; ye who would learn the limit of human endurance, and with what bitter anguish and indignant hate, the heart may swell, and yet not burst, peruse these Memoirs!

Mine are no silken sorrows, nor sentimental sufferings; but that stern reality of actual woe, the story of which, may perhaps touch even some of those, who are every day themselves the authors of misery the same that I endured. For however the practice of tyranny may have deadened every better emotion, and the prejudices of interest and education may have hardened the heart, humanity will still extort an involuntary tribute; and men will grow uneasy at hearing of those deeds, of which the doing does not cost them a moment's inquietude.

Should I accomplish no more than this; should I be able, through the triple steel with which the love of money and the lust of domination has encircled it, to

Page 2

reach one bosom--let the story of my wrongs summon up, in the mind of a single oppressor, the dark and dreaded images of his own misdeeds, and teach his conscience how to torture him with the picture of himself, and I shall be content. Next to the tears and the exultations of the emancipated, the remorse of tyrants is the choicest offering upon the altar of liberty!

But perhaps something more may be possible;--not likely--but to be imagined--and it may be, even faintly to be hoped. Perhaps within some youthful breast, in which the evil spirits of avarice and tyranny have not yet gained unlimited control, I may be able to rekindle the smothered and expiring embers of humanity. Spite of habits and prejudices inculcated and fostered from his earliest childhood--spite of the allurements of wealth and political distinction, and the still stronger allurements of indolence and ease--spite of the pratings of hollow hearted priests--spite of the arguments of time-serving sophists--spite of the hesitation and terrors of the weak-spirited and wavering--in spite of evil precept and evil example, he dares--that generous and heroic youth!--to cherish and avow the feelings of a man.

Another Saul among the prophets, he prophecies terrible things in the ear of insolent and luxurious tyranny; in the midst of tyrants he dares to preach the good tidings of liberty; in the very school of oppression, he stands boldly forth the advocate of human rights!

He breaks down the ramparts of prejudice; he dissipates the illusions of avarice and pride; he repeals

Page 3

the enactments, which though destitute of every feature of justice, have sacriligiously usurped the sacred form of law! He snatches the whip from the hand of the master; he breaks forever the fetter of the slave!

In the place of reluctant toil, delving for another, he brings in smiling industry to labor for herself! All nature seems to exult in the change! The earth, no longer made barren by the tears and the blood of her children, pours forth her treasures with redoubled liberality. Existence ceases to be torture; and to live is no longer, to millions, the certainty of being miserable.

Chosen Instrument of Mercy! Illustrious Deliverer! Come! come quickly!

Come!--lest if thy coming be delayed, there come in thy place, he who will be at once, DELIVERER and AVENGER!

CHAPTER II.

THE county in which I was born, was then, and for aught I know, may still be one of the richest and most populous in eastern Virginia. My father, colonel Charles Moore, was the head of one of the most considerable and influential families in that part of the

Page 4

country;--and family, however little weight it may have in other parts of America, at the time I was born, was a thing of no slight consequence in lower Virginia. Nature and education had conspired to qualify colonel Moore to fill with credit, the station in which his birth had placed him. He was a finished aristocrat; and such he showed himself in every word, look and action. There was in his bearing, a conscious superiority, which few could resist, softened and rendered even agreeable by a gentleness and suavity, which flattered, pleased and captivated. In fact, he was familiarly spoken of among his friends and neighbors, as the faultless pattern of a true Virginian gentleman--an encomium, by which they supposed themselves to convey, in the most emphatic manner, the highest possible praise.

When the war of the American Revolution broke out, colonel Moore was a very young man. By birth and education, he belonged, as I have said, to the aristocratic party, which being aristocratic, was of course, conservative. But the impulses of youth and patriotism were too strong to be resisted. He espoused with zeal, the cause of liberty, and by his political activity and influence, contributed not a little to promote it.

Of liberty indeed, he was always a warm and energetic admirer. Among my earliest recollections of him, is the earnestness with which, among his friends and guests, he used to vindicate the cause of the French revolution, which was then going on. Of this revolution, throughout its whole progress, he was a most eloquent advocate and apologist; and though I understood

Page 5

little or nothing of what he said, the spirit and eloquence with which he spoke could not fail to affect me. The rights of man, and the rights of human nature were phrases, which, although at that time, I was quite unconscious of their meaning I heard so often repeated, that they made an indelible impression upon my memory, and in after years, frequently recurred to my recollection.

But colonel Moore was not a mere talker; he had the credit of acting up to his principles, and was universally regarded as a man of the greatest good nature, honor and uprightness. Several promising young men, who afterwards rose to eminence, were indebted for their first start in life, to his patronage and assistance. He settled half the differences of the county, and never seemed so well pleased as when, by preventing a lawsuit or a duel, he hindered an accidental and perhaps trifling dispute from degenerating into a bitter, if not a fatal quarrel. The tenderness of his heart, his ready active benevolence, and his sympathy with misfortune, were traits of his character which were spoken of by every body.

Had I been allowed to choose my own paternity, could I possibly have selected a more desirable father? But by the laws and customs of Virginia, it is not the father but the mother, whose rank and condition determine that of the child;--and alas! my mother was a concubine and a slave!

Yet those who beheld her for the first time, would hardly have imagined, or would willingly have forgotten, that she was connected with an ignoble and degraded

Page 6

race. Humble as her origin might be, she could at least boast the possession of the most brilliant beauty. The trace of African blood, by which her veins were contaminated, was distinctly visible;--but the tint which it imparted to her complexion only served to give a peculiar richness to the blush that mantled over her check. Her long black hair, which she understood how to arrange with an artful simplicity, and the flashing of her dark eyes, which changed their expression with every change of feeling, corresponded exactly to her complexion, and completed a picture which might perhaps be matched in Spain or Italy, but for which, it would be in vain to seek a rival among the pale-faced, languid beauties of eastern Virginia.

I describe her more like a lover than a son. But in truth, her beauty was so uncommon, as to draw my attention while I was yet a child;--and many an hour have I watched her, almost with a lover's earnestness, while she fondled me on her lap, and tears and smiles chased each other alternately over a face, the expression of which was ever changing, yet always beautiful. She was the most affectionate of mothers; the mixture of tenderness, grief and pleasure, with which she always seemed to regard me, gave a new vivacity to her beauty, and it was probably this, which so early and so strongly fixed my attention.

But I was very far from being her only admirer. Her beauty was notorious through all that part of the country; and colonel Moore had been frequently tempted to sell her by the offer of very high prices. All such offers however, he had steadily rejected;

Page 7

for he especially prided himself upon owning the swiftest horse, the handsomest wench, and the finest pack of hounds in all Virginia.

Now it may seem odd, to some people, in some parts of the world, that colonel Moore being such a man as I have described him, should keep a mistress and be the father of illegitimate children. Such persons however, must be totally ignorant of the state of things in the slave-holding states of America.

Colonel Moore was married to an amiable woman, whom, I dare say, he loved and respected; and in the course of time, she made him the happy father of two sons and as many daughters. This circumstance however, did not hinder him, any more than it does any other American planter--from giving, in the mean time, a very free indulgence to his amorous temperament among his numerous slaves at Spring-Meadow,--for so his estate was called. Many of the young women occasionally boasted of his attentions--though generally, at any one time, he did not have more than one or two acknowledged favorites.

My mother was for several years, distinguished by colonel Moore's very particular regard; and she brought him no less than six children,--all of whom, except myself, who was the eldest, were lucky enough to die in infancy.

From my mother I inherited some imperceptible portion of African blood, and with it, the base and cursed condition of a slave. But though born a slave, I inherited all my father's proud spirit, sensitive feelings and ardent temperament; and as regards natural

Page 8

endowments, whether of mind or body, I am bold to assert, that he had more reason to be proud of me than of either of his legitimate and acknowledged sons.

CHAPTER III.

THAT education is the most effectual, which commences earliest--a maxim well understood in that part of the world in which it was my misfortune to be born. As it sometimes happens there, that one half of a man's children are born masters and the other half slaves, it has become sufficiently obvious how necessary it is, to begin, by times, the course of discipline proper to train them up for these very different situations. It is, accordingly, the general custom, that young master, almost from the hour of his birth, has allotted to him, some little slave near his own age, upon whom he begins, from the time that he can go alone, to practice his apprenticeship of tyranny It so happened that within less than a year after my birth, colonel Moore's wife presented him with her second son, James; and while we both slept unconscious in our cradles, I was duly assigned over and appointed to be the body-servant of my younger brother. It is in

Page 9

this capacity, of master James's boy, that following back the traces of memory, I first discover myself.

The natural and usual consequences of giving one child absolute authority over another, may be easily imagined. The love of domination is perhaps the strongest of our passions; and it is surprising how soon the veriest child will become perfect in the practice of tyranny. Of this, colonel Moore's eldest son, William, or master William, as he was called at Spring-Meadow, was a striking instance. He was the terror and bug-bear, not only of Joe, his own boy, but of all the children on the place. That unthinking and irrational delight in the exercise of cruelty, which is sometimes displayed by a wayward child, seemed in him, almost a passion; and this passion by perpetual indulgence, was soon fostered into a habit. When any delinquent slave was to be punished, he contrived if possible to find it out, and to be present at the infliction;--so that he soon became an adept in all the disgusting slang of an overseer. He always went armed with a whip, twice as long as himself; and upon the least opposition to his whims and caprices, was ready to show his skill in the use of it. All this he took some little pains to conceal from his father; who however, was pretty careful not to see what he could, by no means, approve, but what, at the same time--indulgent father as he was--he would have found it very difficult to prevent or to cure.

Master James, to whose service, I was particularly appointed, was a very different boy. Sickly and weak from his birth, his temper was gentle and his mind effeminate.

Page 10

He had an affectionate disposition, and soon conceived a fondness for me, which I very thankfully returned. He protected me from the tyranny of master William by his entreaties, his tears, and what had much more weight with that amiable youth by threats of complaining to his father, and making a complete exposure of his brutal and cruel behaviour.

I soon learned to pardon and put up with an occasional pettishness and ill humor, for which master James' bad health furnished a ready excuse; and by flattery and apparent obsequiousness--for a child learns and practices such arts as readily as a man--I presently came to have a great influence over him. He was the master, and I the slave; but while we were both children, this artificial distinction had less potency, and I found little difficulty in maintaining that actual superiority, to which my superior vigor both of body and mind, so justly entitled me.

When master James had reached the age of five years, it was judged expedient by his father, that he should be initiated into the rudiments of learning. To learn the letters was a laborious undertaking enough,--but for putting them into words, my young master seemed to have no genius whatever. He was not destitute of ambition; he was indeed very desirous to learn; it was the ability, not the inclination that was wanting. In this difficulty, he had recourse to me, who was on all occasions, his chief counsellor. By putting our heads together, we soon hit upon a plan. My memory was remarkably good, while that of my poor little master was very miserable. We arranged

Page 11

therefore, that the family tutor should first learn me the letters and the abs, which my strong memory, we thought, would enable me easily to retain, and which I was gradually, and between plays, as opportunity served, to instil into the mind of master James. This plan we found to answer admirably. Neither the tutor nor colonel Moore made any objection to it;--for all that colonel Moore desired was, that his son should learn to read, and the tutor was very willing to shift off the most laborious part of his task upon my shoulders.

As yet, no one had dreamed of those barbarous and abominable laws--unparalleled in any other codes and destined to be the everlasting disgrace of America--by which it has been made a crime, punishable with fine and imprisonment, to teach a slave to read.

It is not enough that custom and the proud scorn of unfeeling tyranny unite to keep the slave in hopeless and helpless ignorance, but the laws too have openly become a party to this accursed conspiracy! Yes--I believe they would tear out our very eyes,--and that too by virtue of a regularly enacted statute--had they ingenuity enough to invent a way of enabling us to delve and drudge without them!

I soon learned to read, and before long, I made master James almost as good a reader as myself. As he was subject to frequent fits of illness, which confined him to the house, and disabled him from indulging in those active sports to which boys are chiefly devoted, his father obtained for him a large collection of books adapted to his age, which he and I used to read over together, and in which we took great delight.

Page 12

In the further progress of my young master's studies I was still his associate; for though the plan of teaching me first, in order that I might afterwards teach him, was pursued no longer, yet as I had a desire to learn, as well as a quick apprehension, I found no difficulty in extracting every day from master James, the substance of his lessons. Indeed, if there was any difficulty in them, he was in the constant habit of appealing to me for assistance. In this way, I acquired some elementary knowledge of arithmetic and geography, and even a smattering of latin.

These acquisitions however, I took great pains to conceal, since even the fact that I had learned to read, though it increased my consequence among the servants, exposed me to a good deal of ridicule to which I was very sensitive. I was not looked upon, as I suppose they now look upon a slave, who knows how to read and who exhibits some marks of sense and ability, as a dreadful monster breathing war and rebellion, and plotting to cut the throats of all the white people in America. I was regarded rather as a sort of prodigy,--like a three legged hen, or a sheep with four eyes; a thing to be produced and exhibited for the entertainment of strangers. Frequently at a dinner party, after the Madeira had circulated pretty freely, I was set to read paragraphs in the newspapers, to amuse my master's tipsy guests, and was puzzled, perplexed and tormented, by all sorts of absurd, ridiculous, and impertinent questions, which I was obliged to answer under penalty of having a wine glass, a bottle, or a plate flung at my head. Master William especially, as he

Page 13

was prevented from using his whip upon me, as freely as he wished, strove to indemnify himself by making me the butt of his wit. He took great pride in the nick-name of the "learned nigger," which he had invented and always applied to me;--though God knows, that my cheek was little less fair than his, and I cannot help hoping that at least, my soul was whiter.

These, it may be thought, were trifling vexations. In truth they were so--but it cost me many a struggle before I could learn to endure them with any tolerable patience. I was compensated in some measure, by the pleasure I took in listening--as I stood behind my master's chair--to the conversation of the company,--I mean their conversation before they set regularly in to drinking; for every dinner party was sure to wind up with a general frolic.

Colonel Moore kept an open house, and almost every day, he had some of his friends, relatives, or neighbors, at his table. He was himself an eloquent and most agreeable talker;--his voice was soft and musical, and he always expressed himself with a great deal of point and vivacity. Many of his guests were well informed men; and though politics was always the leading topic of conversation, a great variety of other subjects were occasionally discussed. Colonel Moore, as I have already observed, was himself a warm democrat--republican was then the phrase--for democrat, however fond the Americans have since become of the name, was at that time regarded as an epithet of reproach. The greater part of those who frequented colonel Moore's house, entertained the same liberal opinions

Page 14

on political subjects. I listened to their conversation with eagerness and pleasure;--and when I heard them talk of equal rights, and declaim against tyranny and oppression, my heart would swell with emotions of which I scarcely understood the meaning. All this time, I made no personal application of what I heard and felt. It was only the abstract beauty of liberty and equality, of which I had learned to be enamoured. It was the French republicans with whom I sympathized; it was the Austrian and English tyrants against whom my indignation was roused; it was John Adams and his atrocious gag law. I had not yet learned to think about myself. What I saw around me I had always been accustomed to see, and it appeared as it were, the fixed order of nature. Though born a slave, I had, as yet, experienced scarcely any thing of the miseries of that wretched condition. I was singularly fortunate in my young master, to whom I was, in many respects, as much a companion as a servant. By his favor, and through means of my mother, who still continued a favorite with colonel Moore, I enjoyed more indulgences than any other servant on the place. Comparing my situation with that of the field hands, I might pronounce myself fortunate indeed; and though exposed to occasional mortifications, enough to give me already a foretaste of the bitter cup, which every one who lives a slave must swallow, my youth and the buoyant vivacity of my temper as yet sustained me.

At this time, I did not know that colonel Moore was my father. That gentleman was indebted for no inconsiderable portion of his high reputation, to a very

Page 15

strict attention to those conventional observances which so often usurp the place of morals. Some observances of this sort, which prevail in America, are sufficiently curious. It is considered for instance, no crime whatever, for a master to be, if he chooses, the father of every infant slave born upon his plantation. Yet it is esteemed a very grave breach of propriety, indeed almost an unpardonable crime, for such a father ever, in any way, to acknowledge or take any notice, of any of his unfortunate children. Imperious custom demands that he should treat them, in every respect, like his other slaves. If he drives them into the field to labor,--if he sells them at auction to the highest bidder, it is all very well. But if he audaciously undertakes to exhibit towards them, in any way, the slightest indications of paternal tenderness, he may be sure that his character will be assailed by the tongue of universal slander; that his every weak point and unjustifiable action will be carefully sought out, malignantly magnified, and ostentatiously exposed; that he will be compelled to run a sort of moral gauntlet, and will be represented among all the better sort of people, as every thing that is infamous, base and contemptible.

Colonel Moore was by far too wise a man, to entertain the slightest idea of exposing himself to any thing of this sort. He had always kept the best society,--and though he might be a democrat in politics, he was certainly very much of an aristocrat and an exclusive in his feelings. Of course, he had the same sort of indescribable horror, at the thought of violating any of the settled proprieties of the society in which he

Page 16

moved, that a modern belle has, of cotton lace, or a modern dandy of an iron fork. This being the case, nobody will wonder,--so far at least as colonel Moore had any control over the matter--that I was still ignorant who my father was.

But though a secret to me, it certainly was not so to colonel Moore's friends and visitors. If nothing else had betrayed it, the striking resemblance between us, would certainly have done so;--and although that same regard to propriety, which prevented colonel Moore from ever noticing the relationship, tied up the tongues of his guests,--yet, after I had learned the secret, there immediately occurred to my mind the true explanation of certain sly jests and distant allusions, which had sometimes been dropped towards the end of a dinner, by some of those guests whom deep potations had inspired at once with wit and veracity. These brilliancies, of which I had never been able to understand the meaning, were always ill received by colonel Moore, and by all the soberer part of the company, and were frequently followed by a command to me and the other servants to quit the room; but why or wherefore--till I became possessed of the key above mentioned--I was always at a great loss to determine.

The secret which my father did not choose, and which my mother did not dare to communicate to me, I might easily have obtained from my fellow servants. But at this time, like most of the lighter complexioned slaves, I felt a sort of contempt for my duskier brothers in misfortune. I kept myself as much as possible, at a distance from them, and scorned to associate with

Page 17

men a little darker than myself. So ready are slaves to imbibe all the ridiculous prejudices of their oppressors, and themselves to add new links to the chains, which deprive them of their liberty!

But let me do my father justice,--for I do not believe that he was totally destitute of a father's feelings. Though he never made the slightest acknowledgment of the claims which I had upon him, yet I am sure, in his own heart, he did not totally deny their validity. There was a tone of good natured indulgence whenever he spoke to me,--an air of kindness, which--though he always had it--seemed toward me, to have in it something peculiar. At any rate, he succeeded in captivating my affections, for though I regarded him only as my master, I loved him very sincerely.

CHAPTER IV.

I was about seventeen years old, when my mother was attacked by a fever, which proved fatal to her. She early had a presentiment of her fate; and before the disorder had made any great progress, she sent me word that she desired to see me. I found her in bed. She begged the woman who nursed her, to leave us together, and bade me sit down by her bed-side.

Page 18

Having told me that she feared she was going to die, she could not think it kind to me, she said, to leave the world, without first telling me a secret, which possibly, I might find hereafter of some consequence. I begged her to go on, and waited with impatience for the promised information. She began with a short account of her own life. Her mother was a slave; her father was a certain colonel Randolph--a scion of one of the great Virginian families. She had been raised as a lady's maid, and on the marriage of colonel Moore, had been purchased by him and presented to his wife. She was then quite a girl. As she grew older and her beauty became more noticeable, she found much favor in the eyes of her master. She had a neat little house, with a double set of rooms--an arrangement, as much for colonel Moore's convenience as her own;--and though some light tasks of needle-work were sometimes required of her, yet as nobody chose to quarrel with master's favorite, she lived, henceforward, a very careless, indolent, but as she told me, a very unhappy life.

For much of this unhappiness she was indebted to herself. The airs of superiority she assumed in her intercourse with the other servants, made them all hate her, and induced them to improve every opportunity of vexing and mortifying her;--and to all sorts of feminine mortifications she was as sensitive as any belle that ever existed. But though vain of her beauty and her master's favor, she was not ill-tempered; and the foolish pride from which she suffered, sprung in her, as a similar feeling did in me, from a silly, though

Page 19

common prejudice. Indeed our situation was so superior to that of most of the other slaves, that we naturally imagined ourselves, in some sort, a superior race. It was doubtless under the influence of this feeling, that my mother, having told me who my father was, observed with a smile and a self-complacent air, which even the tremors of her fever did not prevent from being visible,--that both on the father's and the mother's side, I had running in my veins, the best blood of Virginia--the blood, she added, of the Moores and the Randolphs!

Alas! she did not seem to recollect that though I might count all the nobility of Virginia among my ancestors, one drop of blood imported from Africa--though that too, might be the blood of kings and chieftains,--would be enough to taint the whole pedigree, and to condemn me to perpetual slavery, even in the house of my own father!

The information which my mother communicated, made little impression on me at the moment. My principal anxiety was for her;--for she had always been the tenderest and most affectionate of parents. The progress of her disorder was rapid, and on the third day she ceased to live. I lamented her with the sincerest grief. The sharpness of my sorrow was soon over; but my spirits did not seem to regain their former tone. The thoughtless gaiety, which till now had shed a sort of sunshine over my life, seemed to have deserted me. My thoughts began to recur, very frequently, to the information which my mother had communicated. I hardly know how to describe the

Page 20

effect which it seemed to have upon me. Nor is it easy to tell what were its actual effects, or what ought to be ascribed to other and more general causes. Perhaps that revolution of feeling, which I now experienced, should be attributed, in a great measure, to the change from boyhood to manhood, through which I was passing. Hitherto things had seemed to happen like the events of a dream, without touching me deeply or affecting me permanently. I was sometimes vexed and dissatisfied,--I had my occasional sorrows and complaints. But these sorrows were soon over, and as after summer showers the sun shines out the brighter, so my transient sadness was soon succeeded by a more lively gaiety, which, as soon as immediate grievances were forgotten, burst forth, unsubdued either by reflections on the past, or anxieties for the future. In this gaiety there was indeed scarcely anything of substantial pleasure:--it originated rather in a careless insensibility. It was like the glare of the moon-beams, bright but cold. Such as it was however, it was far more comfortable, than the state of feeling by which it now began to be succeeded. My mind seemed to be filled with indefinite anxieties, of which I could devine neither the causes nor the cure. There was, as it were, a heavy weight upon my bosom, an unsatisfied craving for something, I knew not what, a longing which I could do nothing to satisfy, because I could not tell its object. I would be often lost in thought,--but my mind did not seem to fix itself to any certain aim, and after hours of apparently the deepest meditation,

Page 21

I should have been very much at a loss, to tell about what I had been thinking.

But sometimes my reflections would take a more definite shape. I would begin to consider what I was and what I had to anticipate. The son of a freeman, yet born a slave! Endowed by nature with abilities, which I should never be permitted to exercise; possessed of knowledge, which already, I found it expedient to conceal! The slave of my own father, the servant of my own brother, a bounded, limited, confined, and captive creature, who did not dare to go out of sight of his master's house without a written permission to do so! Destined to be the sport, of I knew not whose caprices, forbidden in anything to act for myself, or to consult my own happiness,--compelled to labor all my life at another's bidding, and liable every hour and instant, to oppressions the most outrageous, and degradations the most humiliating!

These reflections soon grew so bitter that I struggled hard to suppress them. But this was not always in my power. Again and again, in spite of all my efforts, these hateful ideas would start up and sting me into anguish.

My young master still continued kind as ever. I was changing to a man, but he still remained a boy. His protracted ill health, which had checked his growth, appeared also to retard his mental maturity. He seemed every day to fall more and more under my influence; and every day my attachment to him grew stronger. He was in fact, my sole hope. While I remained with him, I might reasonably expect to escape

Page 22

the utter bitterness of slavery. In his eyes, I was not a mere servant. He regarded me rather as a loved and trusted companion. Indeed, though he had the name and prerogatives of master, I was much less under his control than he was under mine. There was between us, something of a brotherly affection--at least of that kind, which may exist between foster brothers,--though neither of us ever alluded to our actual relationship, and he probably, was ignorant of it.

I loved master James as well as ever; but towards colonel Moore, my feelings underwent a rapid and a radical change. While I considered myself merely as his slave, his apparent kindness had gained my affection; and there was nothing I would not have done or suffered, for so good natured and condescending a master. But after I had learned to look upon myself as his son, I soon began to feel that I might justly claim as a right, what I had till now, regarded as a pure gratuity. I began to feel that I might claim much more,--even an equal birth-right with my brethren. Occasionally, I had read the bible;--and I now turned with new interest to the story of Hagar, the bond-woman, and Ishmael her son;--and as I read how an angel came to their relief, when the hard-hearted Abraham had driven them into the wilderness, there seemed to spring up within me, a wild, strange, uncertain hope, that in some accident, I knew not what, I too might find succor and relief. At the same time, with this irrational hope, a new spirit of bitterness was poured into my soul. Unconsciously I clenched my hands, and set my teeth, and fancied myself, as it were,

Page 23

another Ishmael, wandering in the wilderness, every man's hand against me, and my hand against every man. The injustice of my unnatural parent, stung me deeper and deeper,--and all my love for him was turned into hate. The atrocity of those laws which made me a slave--a slave in the house of my own father,--seemed to glare before my prophetic eyes in letters of blood. Young as I was, and as yet untouched, I trembled for the future, and cursed the country and the hour that gave me birth!

I endeavored, as much as possible, to conceal these new feelings with which I was tormented; and as deceit is one of those defences against tyranny, of which a slave early learns to avail himself, I was not unsuccessful. My young master would sometimes find me in tears; and sometimes when I would be lost in thought, he would complain of my inattention. But I put him off with plausible excuses; and though he suspected there was something which I did not tell him, and would frequently say to me, "Come Archy, boy, let me know what it is that troubles you,"--I would make light of the matter and laugh off his suspicions.

I was now about to lose this kind master, in whose tenderness and affection I found the sole palliative that could make slavery tolerable. His health which had always been bad, grew rapidly worse, and confined him first to his chamber and then to his bed. I attended him during his whole illness with a mother's tenderness and assiduity. Never was master more faithfully served;--but it was the friend, not the slave, who rendered these attentions. He was not insensible to my

Page 24

services; he did not seem to like that any one but I should be about him, and it was only from my hand that he would take his physic or his food. But it was not in the power of physician or of nurse to save him. He wasted daily, and grew weaker every hour. The fatal crisis soon came. His weeping friends were collected about his bed,--but the tears they shed were not as bitter as mine. Almost with his last breath he recommended me to the good graces of his father,--but the man who had closed his heart to the promptings of paternal tenderness, was not likely to give much weight to the requests of a dying son. He bade his friends farewell,--he pressed my hand in his;--and, with a gentle sigh, he expired in my arms.

Would to God, I had died with him!

CHAPTER V.

THE family of colonel Moore knew well how truly I had loved, and how faithfully I had served my young master. They respected the profound depth of my grief, and for a week or two, I was suffered to grieve on unmolested. My feelings were no longer of that acute and piercing kind which I have described in the

Page 25

preceding chapter. The temperament of the mind is forever changing. That state of preternatural sensibility, of which I have attempted to give an idea, had disappeared when my attention became wholly occupied in the care of my dying master, and was now succeeded by a dull and stupid sorrow. Apparently I now had increased cause for agitation and alarm. That which I then dreaded, had now happened. My young master, on whom all my hopes were suspended, lived no longer, and I knew not what was to become of me. But the fit of fear and anxious anticipation was over; and I now waited my fate with a sort of stupid and careless indifference.

Though not called upon to do it, I continued as usual to wait upon my master's table. For several days, I took my place instinctively near where master James' chair ought to have stood; till the sight of the vacant place drove me in tears to the opposite corner. In the mean time, nobody called upon me to do anything, or seemed to notice that I was present. Even master William made an effort to repress his habitual insolence.

But this could not last long. Indeed it was a stretch of indulgence, which no one but a favorite servant could have expected;--since slaves, in general, are thought to have no business to be sorry--if it makes them unable to work.

One morning after breakfast, master William having discussed his toast and coffee, began by telling his father, that in his opinion, the slaves at Spring-Meadow, were a great deal too indulgently treated. He

Page 26

was by this time, a smart, dashing, elegant young man, having returned, upwards of a year before, from college, and quite lately, from Charleston, in South Carolina, whither he had been to spend a winter, and as his father expressed it, to wear off the rusticity of the school-room. It was there perhaps, that he had learned the new precepts of humanity, which he was now preaching. He declared that any tenderness towards a slave only tended to make him insolent and discontented, and was quite thrown away on the ungrateful rascals. Then, looking about, as if in search of some victim on whom to practice a doctrine so consonant to his own disposition, his eye lighted upon me. "There's that boy Archy--I'll bet a hundred to one I could make him one of the best servants in the world. He's a bright fellow enough naturally, and nothing has spoil'd him, but poor James' over indulgence. Come father, just be good enough to give him to me, I want another servant most devlishly."

Without stopping for an answer, he hastened out of the room, having, as he said, two jockey races to attend that morning; and what was more, a cock-fight into the bargain. There was nobody else at the table. Colonel Moore turned towards me. He began with commending very highly, my faithful attachment to his poor son James. As he mentioned his son's name the tears stood in his eyes, and for a moment or two he was unable to speak. He recovered himself presently, and added--"I hope now you will transfer all this same zeal and affection to master William."

These words roused me in a moment. I knew master

Page 27

William to be a tyrant, from whose soul custom had long since obliterated what little humanity nature had ever bestowed upon him;--and to judge from what he had let drop that morning--he had of late improved upon his natural inclination for cruelty, and had proceeded to the final length of reducing tyranny into a system and a science. I knew too that from childhood, he had entertained a particular spite against me; and I dreaded, lest he was already devising the means of inflicting upon me, with interest, all those insults and injuries from which the protection of his younger brother had hitherto shielded me.

It was with horror and alarm, that I found myself in danger of falling into such hands. I threw myself at my master's feet, and besought him, with all the eloquence of grief and fear, not to give me to master William. The terms in which I spoke of his son--though I chose the mildest I could think of--and the horror I expressed at the thought of becoming his servant--though I endeavored as much as possible, to save the father's feelings--seemed to make him angry. The smile left his lip, and his brow grew dark and contracted. I began to despair of escaping the wretched fate that awaited me; and my despair drove me to a very rash and foolish action. For emboldened by the danger of becoming the slave of master William, I dared to hint--though distantly and obscurely--at the information which my mother had communicated to me on her death-bed; and I even ventured something like a half appeal to colonel Moore's paternal tenderness. At first, he did not seem to understand me; but the

Page 28

moment he began to comprehend my meaning, his face grew black as a thunder cloud, then became pale, and immediately was suffused with a burning blush, in which shame and rage were equally commingled. I now gave myself up for lost, and expected an instant out-break of fury;--but after a momentary struggle, colonel Moore seemed to regain his composure,--even the habitual smile returned to his lips,--and without taking any notice of my last appeal, or giving any further signs of having understood it, he merely remarked,--that he did not know how to refuse master William's request, nor could he comprehend the meaning of my reluctance. It was mighty foolish; still he was willing to indulge me so far, as to allow me the choice of entering into master William's service, or going into the field. This alternative was proposed with an air and a manner, which was intended to stop my mouth, and allow me nothing but the bare liberty of choosing. It was indeed, no very agreeable alternative. But any thing,--even the hard labor, scanty fare, and harsh treatment, to which I knew the field hands were subjected,--seemed preferable to becoming the sport of master William's tyranny. I was piqued too, at the cavalier manner in which my request had been treated, and I did not hesitate. I thanked colonel Moore for his great goodness, and at once, made choice of the field. He seemed rather surprised at my selection,--and with a smile, which bordered close upon a sneer, bade me report myself to Mr Stubbs.

An overseer, is regarded in all those parts of slaveholding America, with which I ever became acquainted,

Page 29

very much in the same light in which people, in countries uncursed with slavery, look upon a jailor or a hangman; and as these latter employments, however useful and necessary, have never succeeded in becoming respectable, so the business of an overseer is likely from its nature, always to continue contemptible and degraded. The young lady who dines heartily on lamb, has a sentimental horror of the butcher who killed it; and the slave owner who lives luxuriously on the forced labor of his slaves, has a like sentimental abhorrence of the man who holds the whip and compels the labor. He is like a receiver of stolen goods, who cannot bear the thoughts of stealing himself, but who has no objection to live upon the proceeds of stolen property. A thief is but a thief; and an overseer but an overseer. The slave owner prides himself in the honorable appellation of a planter; and the receiver of stolen goods assumes the character of a respectable shop-keeper. By such contemptible juggle do men deceive not themselves only, but oft-times the world also.

Mr Thomas Stubbs was overseer at Spring-Meadow,--a personage with whose name, appearance and character I was perfectly familiar, though hitherto I had been so fortunate as to have had very little communication with him.

He was a thick set, clumsy man, about fifty, with a little bullet head, covered with short tangled hair, and stuck close upon his shoulders. His face was curiously mottled and spotted,--for what with sunshine, what with whiskey, and what with ague and fever, brown, red and sallow seemed to have put in a joint claim to

Page 30

the possession of it, without having yet been able to arrive at an amicable partition. He was generally to be seen on horseback, leaning forward over his saddle, and brandishing a long thick whip of twisted cow-hide, which from time to time, he applied over the head and shoulders of some unfortunate slave. If you were within hearing, his conversation, or rather his commands and observations, would have appeared a string of oaths, from the midst of which it was not very easy to disentangle his meaning. "You damned black rascal" was pretty sure to begin every sentence, and "by God," to end it. It was however, only when Mr. Stubbs had sole possession of the field, that he sprinkled his orders with this strong spice of brutality;--for when colonel Moore or any other gentleman happened to be riding by, he could assume quite an air of gentleness and moderation, and what appears very surprising, was actually able to express himself, with not more than one oath to every other sentence.

Mr Stubbs, in his management of the plantation did not confine himself to hard words. He used his whip as freely as his tongue. Colonel Moore had received an European education; and like every man educated any where--except on a slave holding estate--he had a great dislike to all unnecessary cruelty. He was usually made very angry, about once a week, by some brutal act on the part of his overseer. But having satisfied his outraged feelings by declaring himself very much offended, and Mr Stubbs' proceedings to be quite intolerable, he ended, with suffering things to go on just as before. The truth was, Mr Stubbs understood

Page 31

making crops; and such a man was too valuable to be given up, for the mere sentimental satisfaction of protecting the slaves from his tyranny.

It was a great change to me, after having been accustomed to the elegance and propriety of colonel Moore's house, and the gentle rule and light service of master James, to pass under the despotic control of a vulgar, ignorant and brutal blackguard. Besides, I had never been accustomed to regular and severe labor; and it was trying indeed to submit at once to the hard work of the field. However, I resolved to make the best of it. I was strong,--and use would soon make my tasks more tolerable. I knew well enough, that Mr Stubbs was totally destitute of all humane feelings, but I had no reason to suppose that he entertained towards me any of that malignity which I had so much dreaded in master William. From what I had known of him, I did not judge him to be a very bad tempered man; and I took it for granted that he cursed and whipped, not so much out of spite and ill feeling, but as a mere matter of business. He seemed to imagine,--like every other overseer,--that it was impossible to manage a plantation in any other way. The lash, I hoped, my diligence might enable me to escape; and Mr Stubbs' vulgar abuse, however provoking the other servants might esteem it, I thought I might easily despise.

Mr Stubbs listened to my account of myself very graciously,--all the time, rolling his tobacco from one cheek to the other, and squinting at me with one of his little twinkling grey eyes. Having cursed me to his satisfaction for "a damned fool," he bade me follow

Page 32

him to the field. A large clumsy hoe, with a handle six feet long, was put into my hands, and I was kept hard at work all day.

At dark, I was suffered to quit the field, and the overseer pointed out to me a miserable little hovel, about ten feet square, and half as many high, with a leaky roof, and without either floor or window. This was to be my house,--or rather I was to share it with Billy, a young slave, about my own age.

To this wretched hut, I removed a chest, containing my clothes and a few other things, such as a slave is permitted to possess. By way of bed and bedding, I received a single blanket, about as big as a large pocket handkerchief; and a basket of corn and a pound or two of damaged bacon, were given me as my week's allowance of provisions. But as I was totally destitute of pot, kettle, knife, plate, or dish of any kind,--for these are conveniences which slaves must procure as they can,--I was in some danger of being obliged to make my supper on raw bacon. Billy saw my distress and took pity on me. He taught me how to beat my corn into hominy; and lent me his own little kettle to cook it in; so that about midnight I was able to break a fast of some sixteen or twenty hours. My chest being both broad and long, served tolerably well for bed, chair and table. I sold a part of my clothes, which were indeed much too fine for a field hand; and having bought myself a knife, a spoon and a kettle, I was able to put my house-keeping into tolerable order.

My accommodations were as good as a field hand had a right to expect; but they were not such as to

Page 33

make me particularly happy; especially as I had been used to something better. My hands were blistered with the hoe, and coming in at night, completely exhausted by a sort of labor to which I was not accustomed, it was no very agreeable recreation, to be obliged to beat hominy, and to be up till after midnight preparing food for the next day, with the recollection too, that I was obliged to turn into the field with the first dawn of the morning. But this labor, severe as it was, had been in a manner, my own choice. In choosing it, I had escaped a worse tyranny and a more bitter servitude. I had avoided falling into the hands of master William.

As I shall not have occasion to mention this amiable youth again, I may as well finish his history here. Some six or eight months after the death of his younger brother, he became involved in a drunken quarrel, at a cock-fight. This quarrel ended in a duel, and master William fell dead at the first fire. His death was a great stroke to colonel Moore, who seemed for a long time, almost inconsolable. I did not lament him either for his own sake or his father's. I knew well, that in his death, I had escaped a cruel and vindictive master; and I felt a stern and bitter pleasure in seeing the bereavements of a man who had dared to trample upon the sacred ties of nature.

Page 34

CHAPTER VI.

I had the same task with those who had been field hands all their lives; but I was too proud to flinch or complain. I exerted myself to the utmost, so that even Mr Stubbs had no fault to find, but on the contrary, pronounced me, more than once, a "right likely hand."

The cabin which I shared with Billy, had a very leaky roof; and as the weather was rainy, we found it, by no means comfortable. At length, we determined one day, to repair it; and to get time to do so, we exerted ourselves to finish our tasks at an early hour.

We had finished about four o'clock in the afternoon, and were returning together to the town,--for so we called the collection of cabins, in which the servants lived. Mr Stubbs met us, and having inquired if we had finished our tasks, he muttered something about our not having half enough to do, and ordered us to go and weed his garden. Billy submitted in silence,--for he had been too long under Mr Stubbs' jurisdiction, to think of questioning any of his commands. But I ventured to say, in as respectful a manner as I could, that as we had finished our regular tasks, it seemed very hard to give us this additional work. This put Mr Stubbs into a furious passion, and he swore twenty oaths, that I should both weed the garden and be whipped into the bargain. He sprang from his horse, and catching me by the collar of my

Page 35

shirt--the only dress I had on,--he began to lay upon me with his whip. It was the first time, since I had ceased to be a child, that I had been exposed to this degrading torture. The pain was great enough, the idea of being whipped was sufficiently bitter,--but these were nothing in comparison with the sharp and burning sense of the insolent injustice that was done me. It was with the utmost difficulty, that I restrained myself from springing upon my brutal tormentor, and dashing him to the ground. But alas!--I was a slave. What in a freeman, is a most justifiable act of self-defence, becomes in a slave, unpardonable insolence and rebellion. I griped my hands, set my teeth firmly together, and bore the injury the best I could. I was then turned into the garden, and the moon happening to be full, I was kept weeding till near midnight.

The next day was Sunday. The Sunday's rest is the sole and single boon for which the American slave is indebted to the religion of his master. That master, tramples under foot every other precept of the Gospel without the slightest hesitation, but so long as he does not compel his slaves to work on Sundays, he thinks himself well entitled to the name of a christian. Perhaps he is so,--but if he is, a title so easily purchased, can be worth but little.

I resolved to avail myself of the Sunday's leisure to complain to my master of the barbarous treatment I had experienced the day before, at the hands of Mr Stubbs. Colonel Moore received me with a coolness and distance, quite unusual in him,--for generally he had

Page 36

a smile for everybody,--especially for his slaves. However, he heard my story, and even condescended to declare that nothing gave him so much pain as to have his servants unnecessarily or unreasonably punished, and that he never would suffer such things to take place upon his plantation. He then bade me go about my business, having first assured me, that in the course of the day, he would see Mr Stubbs and inquire into the matter. This was the last I heard from colonel Moore. That same evening, Mr Stubbs sent for me to his house, and having tied me to a tree before his door, gave me forty lashes, and bade me complain at the house again, if I dared. "It's a damned hard case," he added, "if I can't lick a damned nigger's insolence out of him, without being obliged to give an account of it!"

Insolence!--the tyrant's ready plea!

If a poor slave has been whipped and miserably abused, and no other apology for it can be thought of, the rascal's "insolence" can be always pleaded,--and when pleaded, is enough in every slave-holder's estimation, to excuse and justify any brutality. The slightest word, or look, or action, that seems to indicate the slave's sense of any injustice that is done him, is denounced as insolence, and is punished with the most unrelenting severity.

This was the second time I had experienced the discipline of the lash;--but I did not find the second dose any more agreeable than the first. A blow is esteemed among freemen, the very highest of indignities; and low as their oppressors have sunk them, it is esteemed

Page 37

an indignity even among slaves. Besides--as strange as some people may think it--a twisted cowhide, laid on by the hand of a strong man, does actually inflict a good deal of pain; especially if every blow brings blood.

I will leave it to the reader's own feelings to imagine, what no words can sufficiently describe,--the bitterness of that man's misery, who is every hour in danger of experiencing this indignity and this torture. When he has wrought up his fancy,--and let him thank God, from the very bottom of his heart, that in his case, it is only fancy,--to a lively idea of that misery, he will have taken the first step, towards gaining some notion, however faint and inadequate, of what it is, to be a slave!

I had now learned a lesson, which every slave early learns,--I found that I did not enjoy even the privilege of complaining; and that the only way to escape a reiteration of injustice was, to submit in silence to the first infliction. I did my best to digest this bitter lesson, and to acquire a portion of that hypocritical humility, so necessary to a person in my unhappy condition. Humility,--and whether it be real or pretended, they care but little,--is esteemed by masters, the great and crowning virtue of a slave; for they understand by it, a disposition to submit, without resistance or complaint, to every possible wrong and indignity,--to reply to the most opprobrious and unjust accusations with a soft voice and a smiling face; to take kicks, cuffs and blows as though they were a favor,--to kiss the foot that treads you in the dust!

Page 38

This sort of humility was a virtue, with which, I must confess, nature had but scantily endowed me; nor did I find it so easy, as I might have desired, to strip myself of all the feelings of a man. It was like quitting the erect carriage which I had received at God's hand, and learning to crawl on the earth like a base reptile. This was indeed a hard lesson;--but an American overseer is a stern teacher, and if I learned but slowly, it was not the fault of Mr Stubbs.

CHAPTER VII.

IT would be irksome to myself, and tedious to the reader, to enter into a minute detail of all the miserable and monotonous incidents that made up my life at this time. The last chapter is a specimen, from which it may be judged, what sort of pleasures I enjoyed. They may be summed up in a few words;--and the single sentence which embraces this part of my history, might suffice to describe the whole lives of many thousand Americans. I was hard worked, ill fed, and well whipped. Mr Stubbs having once began with me, did not suffer me to get over the effects of one whipping before he inflicted another; and I have some

Page 39

marks of his about me, which I expect to carry with me to the grave. All this time he assured me, that what he did was only for my own good, and he swore that he would never give over, till he had lashed my damned insolence out of me.

The present began to grow intolerable;--and what hope for the future has the slave? I wished for death; nor do I know to what desperate counsels I might have been driven, when one of those changes, to which a slave is ever exposed, but over which he can exercise no control, afforded me some temporary relief from my distresses.

Colonel Moore, by the sudden death of a relation, had recently become heir to a large property in South Carolina. But the person deceased had left a will, about which there was some dispute, which had every appearance of ending in a lawsuit. The matter required colonel Moore's personal attention; and he had lately set out for Charleston, and had taken with him several of the servants. One or two also had recently died; and Mrs Moore, soon after her husband's departure, sent for me to assist in filling up the gap which had been made in her domestic establishment.

I was truly happy at the change. I knew Mrs Moore to be a lady, who would never insult or trample on a servant, even though he were a slave--unless she happened to be very much out of humor,--an unfortunate occurrence, which in her case, did not happen oftener than once or twice a week--except indeed in the very warm weather, when the fit sometimes lasted for days together.

Page 40

Besides, I hoped that the recollection of my fond and faithful attachment to her younger son, who had always been her favorite, would secure me some kindness at her hands. Nor was I mistaken. The contrast of my new situation, with the tyranny of Mr Stubbs, gave it almost the color of happiness. I regained my cheerfulness, and my buoyant spirits. I was too wise, or rather this new influx of cheerfulness made me too thoughtless, to trouble myself about the future; and satisfied with the temporary relief I experienced, I ceased to brood over the miseries of my condition.

About this time, Miss Caroline, colonel Moore's eldest daughter returned from Baltimore, where she had been living for several years with an aunt, who superintended her education. She was but an ordinary girl, without much grace or beauty. But her maid Cassy,* * Cassandra.

who had formerly been my play-fellow, and who returned a woman, though she had left us a child, was truly captivating.

I learned from one of my fellow servants, that she was the daughter of colonel Moore, by a female slave, who for a year or two had shared her master's favor jointly with my mother, but who had died many years since, leaving Cassy an infant. Her mother was said to have been a great beauty, and a very dangerous rival of mine.

So far as personal charms extended, Cassy was not unworthy of her parentage, either on the father's or

Page 41

the mother's side. She was not tall, but the grace and elegance of her figure could not be surpassed; and the elastic vivacity of all her movements afforded a model, which her languid and lazy mistress,--who did nothing but loll all day, upon a sofa,--might have imitated with advantage. The clear soft olive of her complexion, brightening in either cheek to a rich red, was certainly more pleasing than the sickly, sallow hue, so common, or rather so universal, among the patrician beauties of lower Virginia;--and she could boast a pair of eyes, which for brilliancy and expression, I have never seen surpassed.

At this time, I prided myself upon my color, as much as any white Virginian of them all; and although I had found, by a bitter experience, that a slave, whether white or black, is still a slave; and that the master, heedless of his victim's complexion, handles the whip, with perfect impartiality;--still, like my poor mother, I thought myself of a superior caste, and would have felt it as a degradation, to put myself on a level with men a few shades darker than myself. This silly pride had kept me from forming intimacies with the other servants, either male or female; for I was decidedly whiter than any of them. It had too, justly enough, exposed me to an ill will, of which I had more than once felt the consequences, but which had not yet wholly cured me of my folly.

Cassy had perhaps more African blood than I; but this was a point--however weighty and important, I had at first esteemed it--which, as I became more acquainted with her, seemed continually of less consequence,

Page 42

and soon disappeared entirely from my thoughts. We were much together; and her beauty, vivacity, and good humor, made, every day, a stronger impression upon me. I found myself in love before I had thought of it; and it was not long before I discovered that my affection was not unrequited.

Cassy was one of nature's children, and she had never learned those arts of coquetry,--often as skilfully practised by the maid as the mistress,--by which courtships are protracted. We loved; and before long, we talked of marriage. Cassy consulted her mistress; and the answer was favorable. Mrs Moore listened with equal readiness to me. Women are never happier, than when they have an opportunity to dabble a little, in match-making; nor does even the humble condition of the parties quite deprive the business of all its fascination.

It was determined that our marriage, should be a little festival among the servants. The coming Sunday was fixed on as the day; and a Methodist clergyman, who happened to have wandered into the neighborhood, readily undertook to perform the ceremony. This part of his office, I suppose, he would have performed for any body;--but he undertook it the more readily for us, because Cassy, while at Baltimore, had become a member of the Methodist Society.

I was well pleased with all this;--for it seemed to give to our union something of that solemnity, which properly belonged to it. In general, marriage among the American slaves, is treated as a matter of very little moment. It is a mere temporary union, contracted

Page 43

without ceremony, unrecognized by the laws, little or not at all regarded by the masters, and of course, often but lightly esteemed by the parties. The recollection that the husband may be, any day, sold into Louisiana, and the wife into Georgia, holds out but a slight inducement to draw tight the bonds of connubial intercourse;--and the certainty that the fruits of their marriage--the children of their love--are to be born slaves, and reared to all the privations and calamities of hopeless servitude, is enough to strike a damp into the hearts of the fondest couple. Slaves yield to the impulses of nature, and propagate a race of slaves;--but save in a few rare instances, slavery is as fatal to domestic love as to all the other virtues. Some few choice spirits indeed, will still rise superior to their condition, and when cut off from every other support, will find within their own hearts, the means of resisting the deadly and demoralizing influences of servitude. In the same manner, the baleful poison of the plague or yellow fever--innocent indeed and powerless in comparison!--while it rages through an infected city, and sweeps its thousands and tens of thousands to the grave, finds, here and there, an iron constitution, which defies its total malignity, and sustains itself by the sole aid of nature's health-preserving power.

On the Friday before the Sunday which had been fixed upon for our marriage, colonel Moore returned to Spring-Meadow. His return was unexpected; and by me, at least, very much unwished for. To the other servants, who hastened to welcome him home, he spoke with his usual kindness and good nature;--but

Page 44

though I had come forward with the rest of them, all the notice he took of me, was a single stare of dissatisfaction. He appeared to be surprised--and that too not agreeably--to see me again in the house.

The next day, I was discharged from my duties of house servant, and put again under the control of Mr Stubbs. This touched me to the quick;--but it was nothing to what I felt, the day following, when I went to the house to claim my bride. I was told that she was gone in the carriage with colonel Moore and his daughter, who had ridden out to call upon some of the neighbors;--and that I need not take the trouble of coming again to see her, for Miss Caroline did not choose that her maid should marry a field hand.

It is impossible for me to describe the paroxysm of grief and passion, which I now experienced. Those of the same ardent temperament with myself will easily conceive my feelings; and to persons of a cooler temper, no description can convey an adequate idea. My promised wife snatched from me,--and myself again exposed to the hateful tyranny of a brutal overseer!--and all so sudden too--and with such studied marks of insult and oppression!

I now felt afresh the ill effects of my foolish pride in keeping myself seperate and aloof from my fellow servants. Instead of sympathizing with my misfortune, many of them openly rejoiced at it; and as I had never made a confidant or associate among them, I had no friend whose advice to ask, or whose sympathy to seek. At length, I bethought myself of the Methodist minister, who was to come that evening to marry us,

Page 45

and who had appeared to take a good deal of interest in the welfare of Cassy and myself. I was desirous not only of seeking such advice and consolation as he could afford me, but I wished to save the good man from a useless journey,--and possibly from insult at Spring-Meadow; for colonel Moore looked on all sorts of preachers, and the Methodists especially, with an eye of very little favor.

I knew that the clergyman in question, held a meeting, about five miles off; and I resolved, if I could get leave, to go and hear him. I applied to Mr. Stubbs for a pass,--that is, a written permission, without which no slave can go off the plantation to which he belongs, except at the risk of being stopped by the first man he meets, horsewhipped, and sent home again. But Mr Stubbs swore that he was tired of such gadding, and he told me that he had made up his mind to grant no more passes for the next fortnight.

To some sentimental persons, it may seem hard after the poor slave has labored six days for his master, and the blessed seventh at length gladdens him with its beams, that he cannot be allowed a little change of scene, but must still be confined to the hated fields, the daily witnesses of his toils and his sufferings. Yet many thrifty managers and good disciplinarians are, like Mr Stubbs, very much opposed to all gadding, and they pen up their slaves, when not at work, as they pen up their cattle, to keep them, as they say, out of mischief.

At another time, this new piece of petty tyranny, might have provoked me;--but now, I scarcely regarded

Page 46

it;--for my whole heart was absorbed by a greater passion. I was slowly returning towards the servants' quarter, when a little girl, one of the house servants, came running up to me, almost out of breath. I knew her to be one of Cassy's favorites, and I caught her in my arms. As soon as she had recovered her breath, she told me she had been looking for me, all the morning, for she had a message for me from Cassy;--that Cassy had been obliged, much against her inclination, to go out that morning with her mistress, but that I must not be alarmed or down-hearted, for she loved me as well as ever.

I kissed the little messenger, and thanked her a thousand times for her news. I then hastened to my house. This was quite a comfortable little cottage, which Mrs Moore had ordered to be built for Cassy and myself, but of which, I expected every moment to be deprived. The news I had heard, excited new commotions in my bosom. I had no sooner sat down, than I found it impossible to keep quiet. My heart beat violently,--the fever in my blood grew high. I left the house and I walked about, within the limits of my jail yard,--for so I might justly esteem the plantation; I used the most violent exercise, and tried every means I could think of to subdue the powerful emotions of mixed hope and fear, with which I was agitated, and which I found more oppressive than even the certainty of misery.

As evening drew on, I watched for the return of the carriage; and at length, its distant rumbling caught my ear. I hastened towards the house, in the hope of

Page 47

seeing Cassy, and perhaps, of speaking with her. The carriage stopped at the door, and I was fast approaching it; but at the instant, it occurred to me, that it would be better not to risk being seen by colonel Moore, who, I was now well satisfied, entertained a decided hostility towards me, and whom I believed to be the author of the cruel repulse I had that morning met with. This thought stopped me, and I drew back and returned home, without catching a glimpse, or exchanging a word.

I threw myself upon my bed;--but I turned contintinually from side to side, and found it impossible to compose myself to rest. Hour after hour dragged on; but I could not sleep. It was past midnight; when I heard a slight tap at the door, and a soft whisper, which thrilled through every nerve. I sprung up--I opened the door--I clasped her to my bosom. It was Cassy--it was my betrothed wife.

She told me, that since colonel Moore's return, every thing seemed changed at the House. Miss Caroline had told her, that colonel Moore had a very bad opinion of me, and was very much displeased to find, that during his absence I had been again employed as one of the house servants. She added, that when he was told of our intended marriage, he had declared that Cassy was too pretty a girl to be thrown away upon such a scoundrel, and that he would undertake to provide her with a much better husband. So her mistress had bidden her to think no more of me;--but at the same time, had told her not to cry, for she would never leave off teazing her father, till he had fulfilled

Page 48

his promise; and if you get a husband, the young lady added, that you know is all that any of us want. So thought the mistress;--the maid, I have reason to suppose, was rather more refined in her notions of matrimony.

I was not quite certain how to interpret this conduct of colonel Moore's. I was strongly inclined to consider it, only as a new out-break of that spite and hostility, which I had been experiencing, ever since my useless and foolish appeal to his fatherly feelings. It occurred to me however, as possible, that his opposition to our marriage might spring from other motives. Whatever I might imagine, I kept my own counsel. One motive which occurred to me, I could not think of myself, with the slightest patience; and still less could I bear to shock and distress poor Cassy, by the mention of it. Another motive, which I thought might possibly have influenced colonel Moore, was less discreditable to him, and would have been flattering to the pride of both Cassy and myself. But this, I could not mention, without leading to disclosures, which I did not see fit to make.

Cassy knew herself to be colonel Moore's daughter; but early in our acquaintance, I had discovered that she had no idea, that I was his son. I have every reason to believe, that Mrs Moore was perfectly well informed as to both these particulars,--for they were of that sort, which seldom or never escape the eagerness of female curiosity, and more especially, the curiosity of a wife.

Whatever she might know, she discovered in it no

Page 49

impediment to my marriage with Cassy. Nor did I;--for how could that same regard for the decencies of life--such is the soft phrase which justifies the most unnatural cruelty--that refused to acknowledge our paternity, or to recognize any relationship between us, pretend at the same time, and on the sole ground of relationship, to forbid our union?

But I knew that Cassy felt, rather than reasoned;--and though born and bred a slave, she possessed great delicacy of feeling. Besides, she was a Methodist, and though as cheerful and gay hearted a girl as I ever knew, she was very devout in all the observances of her religion. I feared to put our mutual happiness in jeopardy;--I was unwilling to harrass Cassy, with what I esteemed unnecessary scruples. I had never told her the story of my parentage, and every day I grew less inclined to tell it. Accordingly I made no other answer to what she had told me, except to say, that however little colonel Moore might like me, his dislike was not my fault.

A momentary pause followed;--I pressed Cassy's hand between mine, and in a faultering voice, I asked, what she intended to do: