An Autobiography.

The Story of the Lord's Dealings with Mrs. Amanda Smith

the Colored Evangelist;

Containing an Account of Her Life Work

of Faith, and Her Travels

in America, England, Ireland, Scotland,

India, and

Africa, as

an Independent Missionary:

Electronic Edition.

Amanda Smith, 1837-1915

Funding from the National

Endowment for the Humanities

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Sarah Reuning

Images scanned by

Sarah Reuning

Text

encoded by

Carlene Hempel and Natalia Smith

First edition, 1999

ca. 1.5MB

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

1999.

Source Description:

(title page) An Autobiography

The Story of the Lord's Dealings with Mrs. Amanda Smith the

Colored Evangelist; Containing an Account of Her Life Work of Faith,

and Her Travels in America, England, Ireland, Scotland, India, and Africa, as

an Independent Missionary

Smith, Amanda

iii-xvi, 17-506

Chicago:

Meyer & Brother, Publishers,

108 Washington Street,

1893

Call number Travel E185.97 .S6 (Rare Book Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American

South.

Any hyphens occurring

in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks,

em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and

left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and

left quotation marks are encoded as '

and ' respectively.

All em dashes are

encoded as --

Indentation in lines

has not been preserved.

Running titles have

not been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text using

Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings

LC Subject Headings:

- Smith, Amanda, 1837-1915.

- Slaves -- United States -- Biography.

- Women evangelists -- United States -- Biography.

- African American evangelists -- United States -- Biography.

- African American women -- Biography.

- African Americans -- Religious life.

- Freedmen -- United States -- Biography.

- Underground railroad.

- Slaves' writings, American.

- 1999-06-24,

Celine Noel and Sam McRae

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

1999-05-24,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

1999-05-19,

Carlene Hempel

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 1999-04-24,

Sarah Reuning

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY

THE STORY OF THE LORD'S DEALINGS WITH

MRS. AMANDA SMITH

THE COLORED EVANGELIST

CONTAINING AN ACCOUNT OF HER LIFE WORK OF

FAITH, AND HER TRAVELS

IN AMERICA, ENGLAND, IRELAND, SCOTLAND, INDIA AND

AFRICA, AS AN INDEPENDENT MISSIONARY.

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

BISHOP THOBURN, OF INDIA.

"Hitherto the Lord hath helped me."

CHICAGO:

MEYER & BROTHER, PUBLISHERS,

108 WASHINGTON STREET,

1893.

Page verso

Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1893,

by

AMANDA SMITH

in the office of the Librarian of Congress at Washington.

Page iii

PREFACE.

For a number of years many of my friends have said to me, "You ought to write out an account of your life, and let it he known how God has led you out into His work."

Some time before that wonderful man of God, John S. Inskip, passed away, he said, "Amanda, you ought to write," and he kindly offered to assist me in getting the items together.

Many other friends in America, have said the same, and I have replied, "I could not do it, for I don't know how to go about it," and so would not entertain the thought.

Time passed on, and after I was in England a while, the friends there began to say the same thing, and as an inducement to commence, told me that it might be done much cheaper there than in America.

As I was constantly on the go, and had no time to think about it, and certainly none to write, things remained thus until after my return from Africa. Then friends in different places again urged me to do this, and being broken down in health, and so unable to labor as much as formerly, I began to think of it more seriously and prayed much over it, asking the Lord, if it was His will, to make it clear and settle me in it, and give me something from His Word that I may have as an anchor.

Asking thus for light and guidance, I opened my Bible while in prayer, and my eye lighted on these words: "Now, therefore, perform the doing of it, and as there was a readiness to will, so there may be a performance also out of that which ye have." (2nd Cor. viii: 11.)

I said, "Lord, I thank Thee, for this is Thy Word to me, for what I have asked of Thee. Praised be Thy name."

Page iv

And from that moment, my heart was settled to do it. But as the time has gone, and so much has seemed to come if) to hinder, and several persons who had kindly offered to assist me, were called away in one direction or another, and I was so wearied and the task looked so big, my heart began to fail me, and I thought I could not do it.

Again I went to the Lord in prayer, and told Him all about it, and asked Him what I should do, for His glory alone was all I sought. He whispered to my heart, clearly and plainly, these words, "Fear thou not, I will help thee." (Isa. xli: 13.) Again I praised Him; so now I go forward with full faith and trust that He will fulfill His own promise.

My friends who know me best, will make allowances for all defects in this autobiographical sketch; and I believe strangers also will be charitable, when they know that my opportunities for an education have been very limited indeed.

Three months of schooling was all I ever had. That was at a school for whites; though a few colored children were permitted to attend. To this school my brother and I walked five and a half miles each day, in going and returning, and the attention we received while there was only such as the teacher could give after the requirements of the more favored pupils had been met.

In view of the deficiency in my early education, and other disadvantages in this respect, under which I have labored, I crave the indulgence of all who may read this simple and unvarnished story of my life.

AMANDA SMITH.

Page v

INTRODUCTION.

During the summer of 1876, while attending a camp meeting Epworth Heights, near Cincinnati, my attention was drawn to a colored lady dressed in a very plain garb, which reminded me somewhat of that worn by the Friends in former days, who was engaged in expounding a Bible lesson to a small audience.

I was told that the speaker was Mrs. Amanda Smith, and that she was a woman of remarkable gifts, who had been greatly blessed in various parts of the country.

Having spent nearly all my adult years on the other side of the globe, my acquaintance in America was by no means an extensive one, and this will explain the fact that I had never heard of this devout lady until I met her at this camp meeting.

Her remarks on the Bible lesson did not particularly impress me, and it was not until the evening of the same day, when I chanced to be kneeling near her at a prayer meeting, that I became impressed that she was a person of more than ordinary power.

The meetings of the day had not been very successful, and a spirit of depression rested upon many of the leaders. A heavy rain had fallen, and we were kneeling somewhat uncomfortably in the straw which surrounded the preacher's stand.

A number had prayed, and I was myself sharing the general feeling of depression, when I was suddenly startled by the voice of song. I lifted my head, and at a short distance, probably not more than two yards from me, I saw the colored sister of the morning kneeling in an upright position, with her hands spread out and her face all aglow.

She had suddenly broken out with a triumphant song, and while I was startled by the change in the order of the meeting, I was at once absorbed with interest in the song and the singer.

Page vi

Something like a hallowed glow seemed to rest upon the dark face before me, and I felt in a second that she was possessed of a rare degree of spiritual power.

That invisible something which we are accustomed to call power, and which is never possessed by any Christian believer except as one of the fruits of the indwelling Spirit of God, was hers in a marked degree.

From that time onward I regarded her as a gifted worker in the Lord's vineyard, but I had still to learn that the enduement of the Spirit had given her more than the one gift of spiritual power.

A week later I met her at Lakeside, Ohio, and was again impressed in the same way, but I then began to discover that she was not only a woman of faith, but that she possessed a clearness of vision which I have seldom found equaled.

Her homely illustrations, her quaint expressions, her warmhearted appeals, all possess the supreme merit of being so many vehicles for conveying the living truths of the Gospel of Jesus Christ to the hearts of those who are fortunate enough to hear her.

A few years after my return to India, in 1876, I was delighted to hear that this chosen and approved worker of the Master had decided to visit this country. She arrived in 1879, and after a short stay in Bombay, came over to the eastern side of the empire, and assisted us for some time in Calcutta. She also returned two years later, and again rendered us valuable assistance.

The novelty of a colored woman from America, who had in her childhood been a slave, appearing before an audience in Calcutta, was sufficient to attract attention, but this alone would not account for the popularity which she enjoyed throughout her whole stay in our city.

She was fiercely attacked by narrow minded persons in the daily papers, and elsewhere, but opposition only seemed to add to her power.

During the seventeen years that I have lived in Calcutta, I have known many famous strangers to visit the city, some of whom attracted large audiences, but I have never known anyone who could draw and hold so large an audience as Mrs. Smith.

She assisted me both in the church and in open-air meetings, and never failed to display the peculiar tact for which she is remarkable.

I shall never forget one meeting which we were holding in an

Page vii

open square, in the very heart of the city. It was at a time of no little excitement, and some Christian preachers had been roughly handled in the same square a few evenings before. I had just spoken myself, when I noticed a great crowd of men and boys, who had succeeded in breaking up a missionary's audience on the other side of the square, rushing towards us with loud cries and threatening gestures.

If left to myself I should have tried to gain the box on which the speakers stood, in order to command the crowd, but at the critical moment, our good Sister Smith knelt on the grass and began to pray. As the crowd rushed up to the spot, and saw her with her beaming face upturned to the evening sky, pouring out her soul in prayer, they became perfectly still, and stood as if transfixed to the spot! Not even a whisper disturbed the solemn silence, and when she had finished we had as orderly a meeting as if we had been within the four walls of a church!

In those days a well known theatrical manager, much given to popular buffoonery, wrote to me inviting me to arrange to have Mrs. Smith preach in his theatre on a certain Sunday evening. I was much surprised on receiving the letter, and taking it to her told her I did not know what it meant. Several friends, who chanced to be present, at once began to dissuade her:

"Do not go, Sister Amanda," said several, speaking at once, "the man merely wishes to have a good opportunity of seeing you, so that he can take you off in his theatre. He has no good purpose in view. Do not trust yourself to him under any circumstances."

After a moment's hesitation Mrs. Smith replied in language which I shall never forget:

"I am forbidden," she said, "to judge any man. You would not wish me to judge you, and would think it wrong if any of us should judge a brother or sister in the church. What right have I to judge this man? I have no more right to judge him than if he were a Christian."

She said she would pray over it and give her decision. She did so, and decided to accept the invitation.

When Sunday evening came the theatre was packed like a herring box, while hundreds were unable to gain admission. I took charge of the meeting, and after singing and prayer introduced our strange friend from America.

Page viii

She spoke simply and pointedly, alluding to the kindness of the manager who had opened the doors of his theatre to her, in very courteous terms, and evidently made a deep and favorable impression upon the audience. There was no laughing, and no attempt was ever made subsequently to ridicule her. As she was walking off the stage the manager said to me;

"If you want the theatre for her again do not fail to let me know. I would do anything for that inspired woman."

During Mrs. Smith's stay in Calcutta she had opportunities for seeing a good deal of the native community. Here, again, I was struck with her extraordinary power of discernment. We have in Calcutta a class of reformed Hindus called Brahmos. They are, as a class, a very worthy body of men, and at that time were led by the distinguished Keshub Chunder Sen.

Every distinguished visitor who comes to Calcutta is sure to seek the acquaintance of some of these Brahmos, and to study, more or less, the reformed system which they profess and teach. I have often wondered that so few, even of our ablest visitors, seem able to comprehend the real character either of the men or of their new system. Mrs. Smith very quickly found access to some of them, and beyond any other stranger whom I have ever known to visit Calcutta, she formed a wonderfully accurate estimate of the character, both of the men and of their religious teaching.

She saw almost at a glance all that was strange and all that was weak in the men and in their system.

This penetrating power of discernment which she possesses in so large a degree impressed me more and more the longer I knew her. Profound scholars and religious teachers of philosophical bent seemed positively inferior to her in the task of discovering the practical value of men and systems which had attracted the attention of the world!

I have already spoken of her clearness of perception and power of stating the undimmed truth of the Gospel of Christ. Through association with her, I learned many valuable lessons from her lips, and once before an American audience, when Dr. W. F. Warren was exhorting young preachers to be willing to learn from their own hearers, even though many of the hearers might be comparatively illiterate, I ventured to second his exhortation by telling the audience that I had learned more that had been of

Page ix

actual value to me as a preacher of Christian truth from Amanda Smith than from any other one person I had ever met.

Throughout Mrs. Smith's stay in India she was always cheerful and hopeful. In this respect, too, she differed from most visitors to our great empire. Some adopt gloomy views as they look at the weakness of Christianity, and observe the stupendous fortifications which have been reared by the followers of the various false religions of the people.

Some even yield to despair, and refuse to believe that India ever can be saved or even benefited, while only a very few are able to believe not only that India will yet become a Christian empire, but that Christ will yet lift up the people of this land, and so revolutionize or transform society as it exists to-day, as to make the people practically a new people.

Our good Sister Amanda Smith never belonged to any of these despondent classes.

She sometimes was touched by the pictures of misery which she saw around her, but never became hopeless. She was of cheerful temperament, it is true, but aside from personal feeling, she always possessed a buoyant hope and an overcoming faith, which made it easy for her to believe. that the Saviour, whom she loved and served, really intended to save and transform India.

Soon after Mrs. Smith's visit to India, another Virginian visited Calcutta on his way around the globe. This was Mr. Moncure D. Conway.

These two persons, Mrs. Smith and Mr. Conway, were representative Virginians. They had been born in the same section of the country, brought up as Methodists, and were thoroughly acquainted, one by observation and the other by experience, with the terrible character of the American slave system.

Mr. Conway in early life was for several years a Methodist preacher, but by his own published confession he never comprehended what the true spirit of Methodism was. He was at one time a well known and somewhat popular Unitarian minister, but finding the Unitarians too narrow and orthodox for a man of his liberal mind, he set up an independent church or organization of some kind, in London, and preached to an obscure little congregation for a number of years, until his last experiment ended in confessed failure.

His recorded impressions received in India were of the most

Page x

gloomy kind. He saw nothing to hope for in the condition of the people, and looked at them in their helpless state with blank bewilderment, if not despair. He passed through the empire without leaving a single trace of light behind him, without making an impression for good upon any heart or life, without finding an open door by which to make any man or woman happier or better, without, in short, seeing even a single ray of hope shining upon what he regarded as a dark and benighted land.

Mrs. Smith, the other Virginian, without a tittle of Mr. Conway's learning, and deprived of nearly every advantage which he had enjoyed, not only retained the faith of her childhood, but matured and developed it until it attained a standard of purity and strength rarely witnessed in our world.

She also came to India, but unlike the other Virginian, she cherished hope where he felt only despair, she saw light where he perceived only darkness, she found opportunities everywhere for doing good which wholly escaped his observation, and during her two years' stay in the country where she went, she traced out a pathway of light in the midst of the darkness!

As she left the country she could look back upon a hundred homes which were brighter and better because of her coming, upon hundreds of hearts whose burdens had been lightened and whose sorrows had been sweetened by reason of her public and private ministry.

She is gratefully remembered to this day by thousands in the land.

Her life affords a striking comment at once upon the value of the New Testament to those who receive it, both in letter and in spirit, and upon the hopelessness of the Gospel of unbelief which obtains so wide a hearing at the present day.

A thousand Virginians of the Conway stripe might come and go for a thousand years without making India any better, but a thousand Amanda Smiths would suffice to revolutionize an empire!

I am very glad to learn that Mrs. Smith has at last been induced to yield to the importunities of friends and prepare a sketch of her eventful life. I trust that the story will be told without reserve in all its simplicity, as well as in all its strength, and I doubt not that God will crown this last of her many labors with abundant blessings.

J. M. THOBURN.

CALCUTTA, October 22, 1891

Page xi

CONTENTS.

- CHAPTER I. . . . . 17

BIRTH, PARENTAGE AND DELIVERANCE FROM SLAVERY THROUGH THE CONVERSION OF MY MOTHER'S YOUNG MISTRESS—MY PIOUS GRANDMOTHER. - CHAPTER II. . . . . 24

REMOVAL TO PENNSYLVANIA—GOING TO SCHOOL—FIRST RELIGIOUS EXPERIENCES—PERNICIOUS READING. - CHAPTER III. . . . . 31

SOME OF THE REMEMBRANCES OF MY GIRLHOOD DAYS—HELPING RUNAWAYS—MY MOTHER AROUSED—A NARROW ESCAPE—A TOUCHING STORY. - CHAPTER IV. . . . . 39

MOVING FROM LOWE'S FARM—MARRIAGE—CONVERSION. - CHAPTER V. . . . . 50

HOW I BOUGHT MY SISTER FRANCES AND HOW THE LORD PAID THE DEBT. - CHAPTER VI. . . . . 57

MARRIAGE AND DISAPPOINTED HOPES—RETURN TO PHILADELPHIA—A STRANGER IN NEW YORK—MOTHER JONES' HELP—DEATH OF MY FATHER. - CHAPTER VII. . . . . 73

THE BLESSING—ABOUT SEEKING SANCTIFICATION BY WORKS.

Page xii - CHAPTER VIII. . . . . 92

MY FIRST TEMPTATION, AND OTHER EXPERIENCES—I GO TO NEW UTRECHT TO SEE MY HUSBAND—A LITTLE EXPERIENCE AT BEDFORD STREET CHURCH, NEW YORK—FAITH HEALING. - CHAPTER IX. . . . . 103

VARIOUS EXPERIENCES—HIS PRESENCE—OBEDIENCE—MY TEMPTATION TO LEAVE THE CHURCH—WHAT PEOPLE THINK—SATISFIED. - CHAPTER X. . . . . 121

"THY WILL BE DONE," AND HOW THE SPIRIT TAUGHT ME ITS MEANING, ALSO THAT OF SOME OTHER PASSAGES OF SCRIPTURE—MY DAUGHTER MAZIE'S CONVERSION. - CHAPTER XI. . . . . 132

MY CALL TO GO OUT—AN ATTACK FROM SATAN—HIS SNARE BROKEN—MY PERPLEXITY IN REGARD TO THE TRINITY—MANIFESTATION OF JESUS— WAS IT A DREAM? - CHAPTER XII. . . . . 147

MY LAST CALL—HOW I OBEYED IT, AND WHAT WAS THE RESULT. - CHAPTER XIII. . . . . 164

MY REMEMBRANCES OF CAMP MEETING—SECOND CAMP MEETING—SINGING—OBEDIENCE IS BETTER THAN SACRIFICE. - CHAPTER XIV. . . . . 176

KENNEBUNK CAMP MEETING—HOW I GOT THERE, AND WAS ENTERTAINED—A GAZING STOCK—HAMILTON CAMP MEETING—A TRIP TO VERMONT—THE LOST TRUNK, AND HOW IT WAS FOUND. - CHAPTER XV. . . . . 193

MY EXPERIENCE AT DR. TAYLOR'S CHURCH, NEW YORK, AND ELSEWHERE—THE GENERAL CONFERENCE AT NASHVILLE—HOW I WAS TREATED AND HOW IT ALL CAME OUT—HOW THINGS CHANGE.

Page xiii - CHAPTER XVI. . . . . 205

HOW I GOT TO KNOXVILLE, TENN., TO THE NATIONAL CAMP MEETING, AND WHAT FOLLOWED. - CHAPTER XVII. . . . . 215

SEA CLIFF CAMP MEETING, JULY, 1872—FIRST THOUGHTS OF AFRICA—MAZIE'S EDUCATION AND MARRIAGE—MY EXPERIENCE AT YARMOUTH. - CHAPTER XVIII. . . . . 225

PITTMAN CHURCH, PHILADELPHIA—HOW I BECAME THE OWNER OF A HOUSE, AND WHAT BECAME OF IT—THE MAYFLOWER MISSION, BROOKLYN—AT DR. CUYLER'S. - CHAPTER XIX. . . . . 240

BROOKLYN—CALL TO GO TO ENGLAND—BALTIMORE—VOYAGE OVER. - CHAPTER XX. . . . . 255

LIME STREET STATION, LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND, AND THE. RECEPTION I MET WITH THERE—PAGES FROM MY DIARY. - CHAPTER XXI. . . . . 266

VISIT TO SCOTLAND, LONDON, AND OTHER PLACES—; CONVERSATION WITH A CURATE—GREAT MEETING AT PERTH—HOW I CAME TO GO TO INDIA. - CHAPTER XXII. . . . . 286

IN PARIS—ON THE WAY TO INDIA—FLORENCE—ROME—NAPLES—EGYPT. - CHAPTER XXIII. . . . . 300

INDIA—NOTES FROM MY DIARY—BASSIM—A BLESSING AT FAMILY PRAYER—NAINI TAL—TERRIBLE FLOODS AND DESTRUCTION OF LIFE. - CHAPTER XXIV. . . . . 317

THE GREAT MEETING AT BANGALORE—THE ORPHANAGE AT COLAR—BURMAH—CALCUTTA—ENGLAND.

Page xiv - CHAPTER XXV. . . . . 331

AFRICA—INCIDENTS OF THE VOYAGE—MONROVIA—FIRST FOURTH OF JULY THERE—A SCHOOL FOR BOYS—CAPE PALMAS—BASSA—TEMPERANCE WORK—THOMAS ANDERSON - CHAPTER XXVI. . . . . 346

FORTSVILLE—TEMPERANCE MEETINGS—EVIL CUSTOMS—THOMAS BROWN—BALAAM—JOTTINGS FROM THE JUNK RIVER—BROTHER HARRIS IS SANCTIFIED. - CHARTER XXVII. . . . . 362

CONFERENCE AT MONROVIA—ENTERTAINING THE BISHOP—SIERRA LEONE—GRAND CANARY—A STRANGE DREAM—CONFERENCE AT BASSA—BISHOP TAYLOR. - CHAPTER XXVIII. . . . . 378

OLD CALABAR—VICTORIA'S JUBILEE—CAPE MOUNT—CLAY-ASHLAND HOLINESS ASSOCIATION—RELIGION OF AFRICA—TRIAL FOR WITCHCRAFT—THE WOMEN OF AFRICA. - CHAPTER XXIX. . . . . 393

HOW I CAME TO TAKE LITTLE BOB—TEACHING HIM TO READ—HIS CONVERSION—SOME OF HIS TRIALS, AND HOW HE MET THEM—BOB GOES TO SCHOOL. - CHAPTER XXX. . . . . 406

NATIVE BABIES—VISIT TO CREEKTOWN—NATIVE SUPERSTITIONS—PRODUCTS OF AFRICA—DISAPPOINTED EMIGRANTS. - CHAPTER XXXI. . . . . 418

LIBERIA—BUILDINGS—THE RAINY SEASON—SIERRA LEONE—ITS PEOPLE—SCHOOLS—WHITE MISSIONARIES—COMMON SENSE NEEDED—BROTHER JOHNSON'S EXPERIENCE—HOW WE GET ON IN AFRICA.

Page xv - CHAPTER XXXII. . . . . 431

CAPE PALMAS—HOW I GOT THERE—BROTHER WARE—BROTHER SHARPER'S EXPERIENCE—A GREAT REVIVAL. - CHAPTER XXXIII. . . . . 451

EMIGRATION TO LIBERIA—SCHOOLS OF LIBERIA—MISSION SCHOOLS—FALSE IMPRESSIONS—IGNORANCE AND HELPLESSNESS OF EMIGRANTS—AFRICAN ARISTOCRACY. - CHAPTER XXXIV. . . . . 466

LETTERS AND TESTIMONIALS—BISHOP TAYLOR— CHURCH AT MONROVIA—UPPER CALDWELL—_ SIERRA LEONE—GREENVILLE—CAPE PALMAS BAND OF HOPE TEMPERANCE SOCIETY AT MONROVIA—LETTERS—MRS. PAYNE—MRS. DENMAN—MRS. INSKIP—REV. EDGAR M. LEVY—ANNIE WITTENMYER—DR. DORCHESTER—MARGARET BOTTOME—MISS WILLARD—LADY HENRY SOMERSET. - CHAPTER XXXV. . . . . 486

RETURN TO LIVERPOOL—FAITH HEALING—BISHOP TAYLOR LEAVES AGAIN FOR AFRICA—USE OF MEANS—THE STORY OF MY BONNET—TOKENS OF GOD'S HELP AFTER MY RETURN FROM AFRICA. - CHAPTER XXXVI. . . . . 498

WORK IN ENGLAND—IN LIVERPOOL, LONDON, MANCHESTER, AND VARIOUS OTHER PLACES—I GO TO SCOTLAND AND IRELAND—SECURE PASSAGE TO NEW YORK—INCIDENTS OF THE VOYAGE—HOME AGAIN—CONCLUDING WORDS.

Page xvi

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

- MRS. AMANDA SMITH, . . . . . Frontispiece.

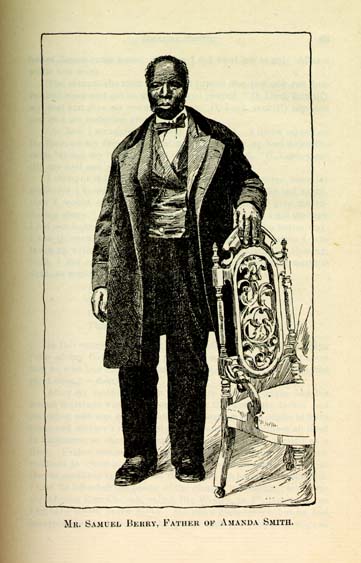

- MR. SAMUEL BERRY, FATHER OF AMANDA SMITH, . . . . . 62

- MAZIE D. SMITH, . . . . . 124

- MARKET PLACE, BOMBAY, . . . . . 300

- PREPARING A MEAL, BOMBAY, . . . . . 304

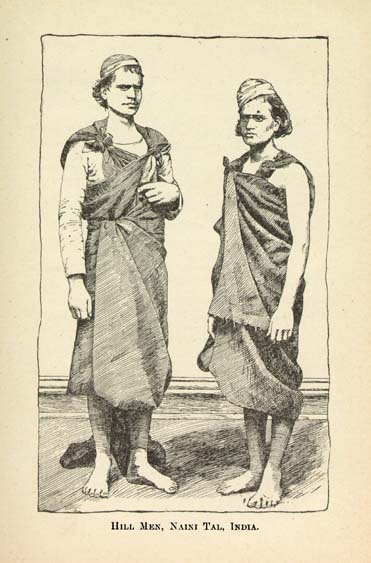

- HILL MEN. NAINI TAL, . . . . . 310

- NIANI TAL, BEFORE THE LAND SLIDE, . . . . . 314

- NATIVE CHRISTIAN FAMILY, INDIA, . . . . . 324

- COOPER'S WHARF, MONROVIA, . . . . . 332

- THE PAINE FAMILY, . . . . . 336

- ASHMAN STREET, MONROVIA, . . . . . 338

- MY FIRST SUNDAY SCHOOL, PLUKIE, . . . . . 348

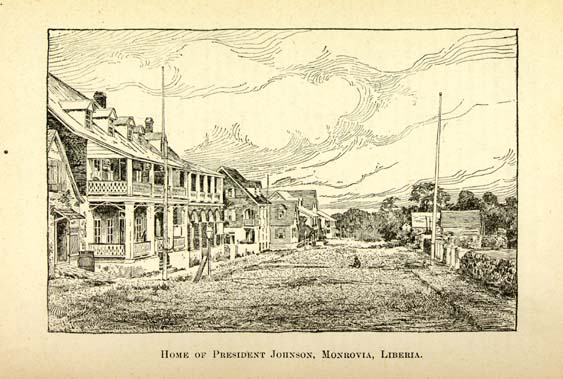

- HOME OF PRESIDENT JOHNSON, . . . . . 352

- NATIVE SOLDIERS, LIBERIA, . . . . . 356

- HOME OF LATE PRESIDENT ROBERTS, . . . . . 364

- KATE ROACH, SIERRE LEONE, . . . . . 368

- ON THE ST. PAUL RIVER, . . . . . 372

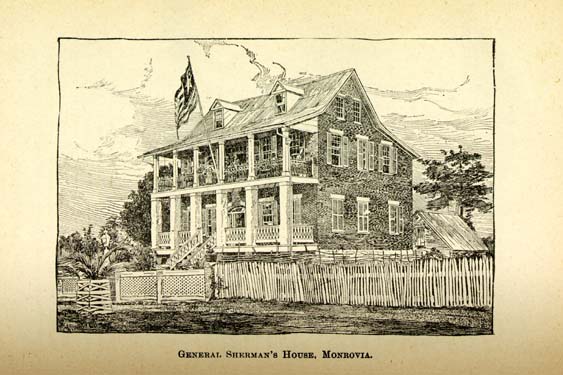

- GENERAL SHERMAN'S HOUSE, MONROVIA, . . . . . 380

- FRANCES, NATIVE BASSA GIRL, . . . . . 390

- BOB, . . . . . 396

- BAPTIST MISSION STATION, . . . . . 420

- BOYS OF MISSION SCHOOL, . . . . . 422

- MISSION SCHOOL, ROTIFUNK, . . . . . 424

- CAPE PALMAS, . . . . . 432

- BISHOP TAYLOR HOLDING A PALAVER, . . . . . 456

- THE RECEPTACLE FOR EMIGRANTS, LIBERIA, . . . . . 460

Page 17

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

OF

AMANDA SMITH.

CHAPTER I.

BIRTH, PARENTAGE AND DELIVERANCE FROM SLAVERY THROUGH THE CONVERSION OF MY MOTHER'S YOUNG MISTRESS—MY PIOUS GRANDMOTHER.

I was born at Long Green, Md., Jan. 23rd, 1837. My father's name was Samuel Berry. My mother's name, Mariam. Matthews was her maiden name. My father's master's name was Darby Insor. My mother's master's name, Shadrach Green. They lived on adjoining, farms. They did not own as large a number of black people, as some who lived in the neighborhood. My father and mother had each a good master and mistress, as was said. After my father's master died, his young master, Mr. E., and himself, had all the charge of the place. They had been boys together, but as father was the older of the two, and was a trustworthy servant, his mistress depended on him, and much was entrusted to his care. As the distance to Baltimore was only about twenty miles, more or less, my father went there with the farm produce once or twice a week, and would sell or buy, and bring the money home to his mistress. She was very kind, and was proud of him for his faithfulness, so she gave him a chance to buy himself. She

Page 18

allowed him so much for his work and a chance to what extra he could for himself. So he used to make brooms and husk mats and take them to market with the produce. This work he would do nights after his day's work was done for his mistress. He was a great lime burner. Then in harvest time, after working for his mistress all day, he would walk three and four miles, and work in the harvest field till one and two o'clock in the morning, then go home and lie down and sleep for an hour or two, then up and at it again. He had an important and definite object before him, and was willing to sacrifice sleep and rest in order to accomplish it. It was not his own liberty alone, but the freedom of his wife and five children. For this he toiled day and night. He was a strong man, with an excellent constitution, and God wonderfully helped him in his struggle. After he had finished paying for himself, the next was to buy my mother and us children. There were thirteen children in all, of whom only three girls are now living. Five were born in slavery. I was the oldest girl, and my brother, William Talbart, the oldest boy. He was named after a gentleman named Talbart Gossage, who was well known all through that part of the country. I think he was some relation of Mr. Ned Gossage, who lost his life at Carlisle, Pa., some time before the war, in trying to capture two of his black boys who had run away for their freedom. I remember distinctly. the great excitement at the time. The law then was that a master could take his slave anywhere he caught him. These boys had been gone for a year or more, and. were in Carlisle when he heard of their whereabouts. He determined to go after them. So he took with him the constable and one or two others. Many of his friends did not want him to go, but he would not hear them. I used to think how strange it was, he being a professed Christian, and a class leader in the Methodist Church, and at the time a leader of the colored people's class, that he should be so blinded by selfishness and greed that he should risk his own life to put into slavery again those who sought only for freedom. How selfishness, when allowed to rule us, will drive us on, and make us act in spirit like the great enemy of our soul, who ever seeks to recapture those who have escaped from the bondage of sin. How we need to watch and pray, and on our God rely.

He did not capture the boys, but in the struggle he lost his own life, and was brought home dead.

Page 19

But I turn again to my story. As I have said, my father having paid for himself was anxious to purchase his wife and children; and to show how the Lord helped in this, I must here tell of the wonderful conversion of my mother's young mistress and of her subsequent death, and the marvelous answer to my grandmother's prayers.

There was a Methodist Camp Meeting held at what was at that time called Cockey's Camp Ground. It was, I think, about twenty miles away, and the young mistress, with a number of other young people, went to this meeting. My mother went along to assist and wait on Miss Celie, as she had always done. It was an old-fashioned, red-hot Camp Meeting. These young people went just as a kind of picnic, and to have a good time looking on. They were staunch Presbyterians, and had no affinity with anything of that kind. They went more out of curiosity, to see the Methodists shout and hollow, than anything else; because they did shout and hollow in those days, tremendously. Of course they were respectful. They went in to the morning meeting and sat down quietly to hear the sermon; then they purposed walking about the other part of the day, looking around, and having a pleasant time. As they sat in the congregation, the minister preached in demonstration of the Power and of the Holy Ghost. My mother said it was a wonderful time. The spirit of the Lord got hold of my young mistress, and she was mightily convicted and converted right there before she left the ground; wonderfully converted in the old-fashioned way; the shouting, hallelujah way. Of course it disgusted those who were with her. They were terribly put out. Everything was spoiled, and they did Dot know how to get her home. They coaxed her, but thank the Lord, she got struck through. Then they laughed at her a little. Then they scolded her, and ridiculed her; but they could not do anything with her. Then they begged her to be quiet; told her if she would just be quiet, and wait till they got home, and wait till morning, they would be satisfied. My mother was awfully glad that the Lord had answered her and grandmother's prayer. As I have heard my mother tell this story she has wept as though it had just been a few days ago. Mother had only been converted about two years before this, and had always prayed for Miss Celie, so her heart was bounding with gladness when Miss Celie was converted. But of course she must hold on and keep as quiet as possible; they had

Page 20

enough to contend with, with Miss Celie. Mother said she sat in the back part of the carriage and prayed all the time. Alter coaxing her awhile she said she would try and keep quiet, and wait till morning. But when she got home she could not keep quiet, but began first thing to praise the Lord and shout. It aroused the whole house, and of course they were frightened, and thought she had lost her mind. But nay, verily, she had received the King, and there was great joy in the city. They got up and wondered what was the matter. They thought she was dreadfully excited at this meeting. They did all they could to quiet her, but they could not do much with her. But finally they did get her quiet and she went to bed. But her heart was so stirred and filled. She wanted to go then to where they would have lively meetings. She wanted to go to the Methodist church. Oh my! That was intolerable. They could not allow that. Then she wanted to go to the colored people's church. No, they would not have that. So they kept her from going. Then they separated my mother and her. They thought maybe mother might talk to her, and keep up the excitement. So they never let them be together at all, if possible. About a quarter of a mile away was the great dairy, and Miss Celie used to slip over there when she got a chance and have a good time praying with mother and grandmother. Finally they found they could do nothing with Miss Celie. So the young people decided they would get together and have a ball and get the notion out of her head. So they planned for a ball, and got all ready. The gentlemen would call on Miss Celie; she was very much admired, anyhow; and they would talk, and they did everything they could. She did not seem to take to it. But finally she said to mother one day, "Well, Mary, it's no use; they won't let me go to meeting anywhere I want to go, and I might as well give up and go to this ball." But my mother said, "Hold on, my dear, the Lord will deliver you." She used to put on her sunbonnet and slip down through the orchard and go down to the dairy and tell mother and grandmother; mother used to assist grandmother in the dairy. One day mother said she came down and said:

"Oh! Mary, I can't hold out any longer; they insist on my going to that ball, and I have decided to go. It's no use." So they had a good cry together, went off and prayed, and that was the last prayer about the ball. How strange! And yet God had that all in his infinite mercy—opening the prison to them

Page 21

that were bound. Just a week before the ball came off, Miss Celie taken down with typhoid fever. They didn't think she was going to die when she was taken down, but they sent for the doctors, the best in the land. Four of them watched over her night and day. Everything was done for her that could be done. She always wanted mother with her, to sit up in the bed and hold her; she seemed only to rest comfortably then. She seemed to have sinking spells. The skill of the doctors was baffled, and they said they could not do any more. So one day after one of these sinking spells, she called them all around her bed and said: "I want to speak to you. I have one request I want to make."

They said, "Anything, my dear."

"I want you to promise me that you will let Samuel have Mariam and the children." Then they had my mother get up out of the bed at once. Of course they didn't want her to hear that; and they said:

"Now, my dear, if you will keep quiet, you may be a little better." And then she went off in a kind of sinking spell. When she said this, and they sent my mother out, she ran with all her might and told grandmother, and grandmother's faith saw the door open for the freedom of her grandchildren; and she ran out into the bush and told Jesus. Of course my mother had to hurry back so as not to be missed in the house. Miss Celie went on that way for three days, and they would quiet her down. When the second day came, and she made the request, and they sent my mother out, she ran and told grandmother that Miss Celie had made the same request; then she ran back to the house again, and grandmother went out and told Jesus. At last it came to the third and last day, and the doctor said: "She can only last such a length of time without there is a change; so what you do, you must do quickly."

Mother was in the bed behind her, holding her up. She called them all again, and said, "I want you to make me one promise; that is, that you will let Samuel have Mariam and the children."

"Oh! yes, my dear," they said, "we will do anything."

My mother was a great singer. When Miss Celie got the promise, she folded her hands together, and leaning her head upon my mother's breast she said, "Now, Mary, sing."

And as best she could, she did sing. It was hard work, for her heart was almost broken, for she loved her as one of her own

Page 22

children. While she sang, Miss Celie's sweet spirit swept through the gate, washed in the blood of the lamb. Hallelujah! what a Saviour. How marvelous that God should lead in this mysterious way to accomplish this end.

I often say to people that I have a right to shout more than some folks; I have been bought twice, and set free twice, and so I feel I have a good right to shout. Hallelujah!

I was quite small when my father bought us, so know nothing about the experience of slavery, because I was too young to have any trials of it. How well I remember my old mistress. She dressed very much after the Friends' style. She was very kind to me, and I was a good deal spoiled, for a little darkey. If I wanted a piece of bread, and if it was not buttered and sugared on both sides, I wouldn't have it; and when mother would get out of patience with me, and go for a switch, I would run to my old mistress and wrap myself up in her apron, and I was safe. And oh! how I loved her for that. They were getting me ready for market, but I didn't know it. I suppose that is why they allowed me to do many things that otherwise I should not have been allowed to do. They used to take me in the carriage with them to church on Sunday. How well I remember my pretty little green satin hood, lined inside with pink. How delighted I was when they used to take me. Then the young ladies would often make pretty little things and give to my mother for me. Mother was a good seamstress; she used to make all of our clothes, and all of father's every day clothes—coats, pants and vests. She had a wonderful faculty in this; she had but to see a thing of any style of dress or coat, or what-not, and she would come home and cut it out. People used to wonder at it. There were no Butterick's patterns then that she could get hold of. So one had to have a good head on them if they kept nearly in sight of things. But somehow mother was always equal to any emergency. My dear old mistress used to knit. I would follow her around. Sometimes she would walk out into the yard and sit under the trees, and I would drag the chair after her; I was too small to carry it. She would sit down awhile, and I would gather pretty flowers. When she got tired she would walk to another spot, and I would drag the chair again. So we would spend several hours in this way. My father had proposed buying us some time before, but could not be very urgent. He had to ask, and then wait a long interval before he could ask again.

Page 23

Two of the young ladies of our family were to be married, and as my brother and myself were the oldest of the children, one of us would have gone to one, and one to the other, as a dowry. But how God moves in a mysterious way His wonders to perform. My grandmother was a woman of deep piety and great faith. I have often heard my mother say that it was to the prayers and mighty faith of my grandmother that we owed our freedom. How I do praise the Lord for a Godly grandmother, as well as mother. She had often prayed that God would open a way so that her grandchildren might be free. The families into which these young ladies were to marry, were not considered by the black folks as good masters and mistresses as we had; and that was one of my grandmother's anxieties. And so she prayed and believed that somehow God would open a way for our deliverance. She had often tried and proved Him, and found Him to be a present help in trouble. And so in the way I have already related, the Lord did provide, and my father was permitted to purchase our freedom.

"In some way or other

The Lord will provide;

It may not be my way,

It may not be thy way,

And yet in His own way,

The Lord will provide."

Page 24

CHAPTER II.

REMOVAL TO PENNSYLVANIA—GOING TO SCHOOL—FIRST RELIGIOUS EXPERIENCES—PERNICIOUS READING.

After my father had got us all free and settled, he wanted to go and see his brother, who had run away for his freedom several years before my father bought himself. The laws of Maryland at that time were, that if a free man went out of the state and stayed over ten days, he lost his residence, and could be taken up and sold, unless some prominent white person interposed; and then sometimes with difficulty they might get him off. But many times poor black men were kidnapped, and would be got out of the way quick. For men who did that sort of business generally looked out for good opportunities. My mother's people all lived in Maryland. She hated to leave her mother, my dear grandmother, and so never would consent to go North. But when my father went away to see his brother, and stayed over the ten days, she thought best to go. Poor mother! How well I remember her. After a week how anxious she was. She used to sit by the fire nearly all night. It was in the fall of the year I know, but I am not able to tell just what year it was. After my father's death, my sister, not knowing the value of the free papers, allowed them all to be destroyed. We were all recorded in the Baltimore court house. Many times I had seen my father show the papers to people. They had a large red seal—the county seal—and my father, or any of us traveling, would have to show our free papers. But those I have not got, so cannot tell the, year or date. But, by and by, the ninth day came. I saw my mother walk the floor, look out of the window, and sigh. I used to get up out of my bed and sit in the corner by the fire and watch her, and see the great tears as she would wipe them away with her apron. She would say; "Amanda, why don't you stay in bed?"

Page 25

I would make an excuse to stay with her. Sometimes I would cry and say I was sick. Then she would call me to her and let me lay my head in her lap; and there is no place on earth so sweet to a child as a mother's lap. I can almost feel the tender, warm, downy lap of my mother now as I write, for so it seemed to me. I loved my father, and thought he was the grandest man that ever lived. I was always the favorite of my father, and I was sorry enough when he was away, and when I saw my mother cry, I would cry, too. Ten days had passed, and father had not come yet.

Every day some of the good farmers around would call to see if "Sam" had got home yet. My father was much respected by all the best white people in that neighborhood, and many of them would not have said anything to him; but, "If nothing was said to Insor's Sam about going out of the state and staying over ten days, why all the niggers in the county would be doing the same thing!"

So this was the cause or the inquiry. Oh! no one knows the sadness and agony of my poor mother's heart. Finally the day came when father returned. Then the friends, white and black, who wished him well, advised him to leave as quickly as possible. And now the breaking up. We were doing well, and father and mother had all the work they could do. The white people in the neighborhood were kind, and gave my mother a good many things, so that we children always had plenty to eat and wear. We had a house, a good large lot, and a good garden, pigs, chickens, and turkeys. And then my mother was a great economist. She could make a little go a great ways. She was a beautiful washer and ironer, and a better cook never lifted a pot. I get my ability in that (if I have any) from my dear mother. Then withal she was an earnest Christian, and had strong faith in God, as did also my grandmother. She was deeply pious, and a woman of marvelous faith and prayer. For the reason stated my parents determined to move from Maryland, and so went to live on a farm owned by John Lowe, and situated on the Baltimore and York turnpike in the State of Pennsylvania.

My father and mother both could read. But I never remember hearing them tell how they were taught. Father was the better reader of the two. Always on Sunday morning after breakfast he would call us children around and read the Bible to us. I

Page 26

never knew him to sit down to a meal, no matter how scant, but what he would ask God's blessing before eating. Mother was very thoughtful and scrupulously economical. She could get up the best dinner out of almost nothing of anybody I ever saw in my life. She often cheered my father's heart when he came home at night and said: "Well, mother, how have you got on to-day?"

"Very well," she would say. It was hard planning sometimes; yet we children never had to go to bed hungry. After our evening meal, so often of nice milk and mush, she would call us children and make us all say our prayers before we went to bed. I never remember a time when I went to bed without saying the Lord's Prayer as it was taught me by my mother. Even before we were free I was taught to say my prayers.

I first went to school at the age of eight years, to the daughter of an old Methodist minister named Henry Dull; my teacher's name was Isabel Dull. She taught a little private school opposite where my mother lived, in a private house belonging to Isaac Hendricks (Bishop Hendricks' grandfather). She was a great friend of my mother's, and was very pretty, and very kind to us children. She taught me my first spelling lesson. There was school only in the summer time. I had about six weeks of it. I first taught myself to read by cutting out large letters from the newspapers my father would bring home. Then I would lay them on the window and ask mother to put them together for me to make words, so that I could read. I shall never forget how delighted I was when I first read: "The house, the tree, the dog, the cow." I thought I knew it all. I would call the other children about me and show them how I could read. I did not get to go to school any more till I was about thirteen years old. Then we had to go about five miles, my brother and myself. There were but few colored people in that part of the country at that time, to go to school (white school), only about five and they were not regular; but father and mother were so anxious for us to go that they urged us on, and I was anxious also. I shall never forget one cold winter morning. The sun was bright, the snow very deep, and it was bitterly cold. My brother did not go that day, but I wanted to go. Mother thought it was too cold; she was afraid I would freeze; but I told her I could go, and after a little discussion she told me I might go. She told me I could put on my brother's heavy boots. I had on a good thick pair of stockings,

Page 27

a warm linsey-woolsey dress, and was well wrapped up. Off I started to my two and a half mile school house,—John Rule's school house on the Turnpike. The first half mile I got on pretty well, a good deal up hill, but O how cold I began to get, and being so wrapped up I couldn't get on so well as I thought I could. I was near freezing to death. My first thought was to go back, but I was too plucky, I was afraid if I told mother she wouldn't let me go again, so I kept still and went. When I got to the school house door, I found I couldn't open it and couldn't speak, and a white boy came up and said, "Why don't you go in?" Then I found I couldn't speak, as I tried and couldn't. He opened the door and I went in and some one came to me and took off my things and they worked with me, I can't tell how long, before I recovered from my stupor. There were a great many farmers' daughters, large girls, and boys, in the winter time, so that the school would be full, so that after coming two and a half miles, many a day I would get but one lesson, and that would be while the other scholars were taking down their dinner kettles and putting their wraps on. All the white children had to have their full lessons, and if time was left the colored children had a chance. I received in all about three months' schooling.

At thirteen years of age I lived in Strausburg, sometimes it was called Shrewsbury, about thirteen miles from York, on the Baltimore and York turnpike. I lived with a Mrs. Latimer. She was a Southern lady, was born in Savannah, Georgia. She was a widow, with five children. It was a good place, Mrs. Latimer was very kind to me and I got on nicely. It was in the spring I went there to live, and sometime in the winter a great revival broke out and went on for weeks at the Allbright Church. I was deeply interested and impressed by the spirit of the meeting. It was an old-fashioned revival, scores were converted. No colored persons went up to be prayed for; there were but few anywhere in the neighborhood. One old man named Moses Rainbow, and his two sons, Samuel and James, were the only colored people that lived anywhere within three or four miles of the town. This meeting went on for four or five weeks. When it closed a series of meetings commenced at the Methodist Church.

One of the members was Miss Mary Bloser, daughter of George Bloser, well known through all that region of country for his deep piety and Christian character, as was Miss Mary, also. She was

Page 28

powerful in prayer. I never heard a young person who knew how to so take hold of God for souls. She was a power for good everywhere she went. How many souls I have seen her lead to the Cross!

One night as she was speaking to persons in the congregation, she came to me, a poor colored girl sitting away back by the door, and with entreaties and tears, which I really felt, she asked me to go forward. I was the only colored girl there, but I went. She knelt beside me with her arm around me and prayed for me. O, how she prayed! I was ignorant, but prayed as best I could. The meeting closed. I went to get up, but found I could not stand. They took hold of me and stood me on my feet. My strength seemed to come to me, but I was frightened. I was afraid to step. I seemed to be so light. In my heart was peace, but I did not know how to exercise faith as I should. I went home and resolved I would be the Lord's and live for him. All the days were happy and bright. I sang and worked and thought that was all I needed to do. Then I joined the Church. I don't remember the name of the minister, but I well remember the name of my class leader was Joshua Ludrick. I liked him for his lung power, for I thought then there was a good deal of religion in loud prayers and shouts. You could hear him pray half a mile when he would get properly stirred. He was leader of the Sunday morning class, which convened after the morning preaching. My father and mother, to encourage me in my new life, joined the Church and the same class, so as to save me from going out at night. Mrs. Latimer's children, three of them, went to the Sunday School, and I must get home so as to have dinner in time for the children to get off, but I was black, so could not be led in class before a white person, must wait till the white ones were through, and I would get such a scolding when I got home, the children would all be so vexed with me, and Mrs. Latimer, and my troubles had begun. I prayed and thought it was my cross. I thought I will change my seat in the class, maybe that will help me, and sat in the first end of the pew, as the leader would always commence on the first end and go down. When I sat in the first end, then he would commence at the lower end and come up and leave me last. Then I sat between two, thinking he would lead the two above me and then lead me in turn, but he would lead the two and then jump across me and lead all the others and lead me last. I told my

Page 29

father I got scolded for getting home so late and making the children late for school. Father said he would speak to Mr. Ludrick about it, but if he did, it made no change, and it came to where I must decide either to give up my class or my service place. We were a large family, and father and mother thought I must keep my situation, so I had to give up my class. It did not do me much good, anyhow, to be scolded every time I went, so I became careless and lost all the grace I had, if I really had any at all. I was light hearted and gay, but I always would say my prayers and read my Bible and good books and meant to get religion when I knew I could keep it. I wouldn't be a hypocrite, no, not I, so I went on, wrapped up in myself. Then I began to watch defects in professors, which is a poor business for any one. That is not the way to get near to God. I saw many things and heard many things said and done by professors that I would not do, I was much better than they were, so I went on in my own way for awhile.

It has been years ago. While living at Black's hotel, in Columbia, I remember reading a book. I forget the title of it, but it was an argument between an infidel and a Christian minister. As I went on reading I became very much interested. "Oh," I thought to myself, "I know the Christian minister will win." It starts with the infidel asking a question. The minister's answer took two pages, while the question asked only took one page and a half. As they went on the minister gained three pages with his answer; and the infidel seemed to lose. And then it went on, and by and by the minister began to lose, and the infidel gained. So it went on till the infidel seemed to gain all the ground. His questions and argument were so pretty and put in such a way that before I knew it I was captured; and by the time I had got through the book I had the whole of the infidel's article stamped on my memory and spirit, and the Christian's argument was lost; I could scarcely remember any of it. Well, I was afraid to tell any one. Oh, if any one should find out that I did not believe in the existence of God. I longed for some one to talk to that I might empty my crop of the load of folly that I had gathered. And I read everything I could get my hands on, so as to strengthen me in my new light, as I thought. Yet I wanted to forget it, and get out of it. But it was like a snare; I could not. A year had gone. I talked big and let out a little bit now and then. How beautiful the old hymn:

Page 30

"When Jesus saw me from on high,

Beheld my soul in ruin lie,

He looked at me with pitying eye,

And said to me as he passed by,

'With God you have no union.' "

Oh, how true! I longed for deliverance, but how to get free. The Lord sent help in this way: My aunt, my mother's half sister, who now lives in Baltimore, and whom I loved very much, came up to York, and then to Wrightsville, to visit father and us children. I lived in Columbia; and I went over to see her and had her come over with me. "Now," I thought, "this will be my chance to unburden my heart. Aunt lives away down in the country in Quaker Bottom, or in the neighborhood of Hereford, Md., and I know no one there, and no one knows me; I shall never be there; and just so that no one knows around here, that is all I care for."

My aunt was very religiously inclined, naturally. She was much like my mother in spirit. So as we walked along, crossing the long bridge, at that time a mile and a quarter long, we stopped, and were looking off in the water. Aunt said, "How wonderfully God has created everything, the sky, and the great waters, etc."

Then I let out with my biggest gun; I said, "How do you know there is a God?" and went on with just such an air as a poor, blind, ignorant infidel is capable of putting on. My aunt turned and looked at me with a look that went through me like an arrow; then stamping her foot, she said:

"Don't you ever speak to me again. Anybody that had as good a Christian mother as you had, and was raised as you have been, to speak so to me. I don't want to talk to you." And God broke the snare. I felt it. I felt deliverance from that hour. How many times I have thanked God for my aunt's help. If she had argued with me I don't believe I should ever have got out of that snare of the devil. And I would say to my readers, "Beware how you read books tainted with error." There are enough of the orthodox kind that will help you if you will be content with them, and the Book of books. Amen.

Page 31

CHAPTER III.

SOME OF THE REMEMBRANCES OF MY GIRLHOOD DAYS— HELPING RUNAWAYS—MY MOTHER AROUSED—A NARROW ESCAPE—A TOUCHING STORY.

The name of my father's landlord was John Lowe, he was a wealthy farmer, lived between New Market and Shrewsburg, Pa. Pretty much all the farmers round about in those days were antislavery men; Joseph Hendricks, Clark Lowe, and a number of others. My father worked a great deal for Isaac Hendricks, who used to keep the Blueball Tavern. I and the children have gathered many a basket of apples out of the orchard, and many a pail of milk I have helped to carry to the house, and often at John Lowe's as well; I used to help them churn often. And then old Thomas Wantlen, who used to keep the store; how well I remember him. John Lowe would allow my father to do what he could in secreting the poor slaves that would get away and come to him for protection. At one time he was Magistrate, and of course did not hunt down poor slaves, and would support the law whenever things were brought before him in a proper way, but my father and mother were level headed and had good broad common sense, so they never brought him into any trouble. Our house was one of the main stations of the Under Ground Railroad. My father took the "Baltimore Weekly Sun" newspaper; that always had advertisements of runaway slaves. After giving the cut of the poor fugitive, with a little bundle on his back, going with his face northward, the advertisement would read something like this: Three thousand dollars reward! Ran away from Anerandell County, Maryland, such a date, so many feet high, scar on the right side of the forehead or some other part of the body,—belonging to Mr. A. or B. So sometimes the excitement was so high we

Page 32

had to be very discreet in order not to attract suspicion. My father was watched closely.

I have known him to lead in the harvest field from fifteen to twenty men—he was a great cradler and mower in those days —and after working all day in the harvest field, he would come home at night, sleep about two hours, then start at midnight and walk fifteen or twenty miles and carry a poor slave to a place of security; sometimes a mother and child, sometimes a man and wife, other times a man or more, then get home just before day. Perhaps he could sleep an hour then go to work, and so many times baffled suspicion. Never but once was there a poor slave taken that my father ever got his hand on, and if that man had told the truth he would have been saved, but he was afraid.

There was a beautiful woods a mile from New Market on the Baltimore and York Turnpike; it was called Lowe's Camp Ground. It was about three quarters of a mile from our house. My mother was a splendid cook, so we arranged to keep a boarding house during the camp meeting time. We had melons, and pies and cakes and such like, as well. Father was very busy and had not noticed the papers for a week or two, so did not know there was any advertisement of runaways. There were living in New Market certain white men that made their living by catching runaway slaves and getting the reward. A man named Turner, who kept the post office at New Market, Ben Crout, who kept a regular Southern blood-hound for that purpose, and John Hunt. These men all lived in New Market. Then there was a Luther Amos, Jake Hedrick, Abe Samson and Luther Samson, his son. I knew them all well. Samson had a number of grey-hounds. So these fellows used to watch our house closely, trying every way to catch my father. One night during camp meeting, between twelve and one o'clock, we children were all on the pallet on the floor. It was warm weather, and father and mother slept in the bed. A man came and knocked at the door. Father asked who was there? He said "A friend. I hear you keep a boarding house and I want to get something to eat."

Father told him to come in. He had everything but hot coffee—so he went to work and got the coffee ready. Father talked with him. The man was well dressed. He had changed his clothes, he said, as he had been traveling, and it was dusty, and he was on his way to the camp meeting. This is what he said

Page 33

to my father. So by and by the coffee was ready, and father set him down to his supper. This man had come through New Market, and Ben Crout and John Hunt, who had read the advertisement, saw this man answered the description and hoping to catch my father, told him to come to our house and all about my father having a boarding house and all about the camp meeting. It was white people's camp meeting, but colored people went as well; it used to be the old Baltimore camp, so called, and so that was the way the poor man knew so well what to say. He had come away from Louisiana, and had been two weeks lying by in the day time and traveling at night, but had got so hungry he ventured into this town, and these men were looking for him, but he did not know it. When they saw him they knew he answered the advertisement given in the paper, for it was always explicitly given; the color, the height and scars on any part of his body. Well, just about the time the man got through with his supper, some one shouted, "Halloo!" Father went to the door. There were six or seven white men, and they said, "We want that nigger you are harboring, he is a runaway nigger."

"I am not harboring anybody," father said. Then they began to curse and swear and rushed upon him. The man jumped and ran up stairs. My mother had a small baby. Of course she was frightened and jumped up, and they were beating father and tramping all over us children on the floor. We were screaming. There stood in the middle of the floor an old fashioned ten plate stove. There was no fire in it, of course, and as my poor frightened mother ran by it trying to defend father, she caught her wrapper in the door, just as a man cut at her with a spring dirk knife; it glanced on the door instead of on mother. I have thanked God many a time for that stove door. But for it my poor mother would have been killed that night. The poor man jumped out of the window up stairs and ran about two hundred yards, when Ben Crout's blood-hound caught him and held him till they came. When they found the man was gone, they left off beating father and went for the man. That was the first and last darkey they ever got out of Sam Berry's clutches. It put a new spirit in my mother. She cried bitterly, but O, when it was all over how she had gathered courage and strength. The good white people all over the neighborhood were aroused, but he was so close to the Maryland line they had him in Baltimore a few hours from then. And, poor fellow, we never heard of him afterwards.

Page 34

Some time, about three or four months after this, along in the fall, we were sleeping upstairs. One night about twelve o'clock a knock came on the fence. My father answered and went down and opened the door. Mother listened and heard them say "runaway nigger." She sprang up, and as she ran downstairs she snatched down father's cane, which had a small dirk in it; she went up and threw open the door, pushed father aside, but he got hold of her, but O, when she got through with those men! They fell back and tried to apologize, but she would hear nothing.

"I can't go to my bed and sleep at night without being hounded by you devils," she said.

Next morning father went off to work, but mother dressed her self and went to New Market; as she went she told everybody she met how she had been hounded by these men. Told all their names right out, and all the rich respectable people cried shame, and backed her up. Dr. Bell, the leading doctor in New Market, who himself owned three or four slaves, stood by my mother and told her to speak of it publicly; so she stood on the stepping stone at Dr. Bell's, right in front of the largest Tavern in the place. There were a lot of these men sitting out reading the news. The morning was a beautiful Fall morning, and she opened her mouth and for one hour declared unto them all the words in her heart. Not a word was said against her, but as the spectators and others looked on and listened the cry of "Shame! Shame!" could be heard; and the men skulked away here and there. By the time she got through there was not one to be seen of this tribe. That morning, as mother went to New Market, this same blood-hound of Bell Crout's was lying on the sidewalk, and as mother went on a lady she used to work for, a Mrs. Rutlidge, saw the dog and saw mother coming. She threw up her hand to indicate to her the dangerous animal. They generally kept her fastened up, but this morning she was not. Mother paid no attention but went on. Mrs. R. clasped her hands and turned her back expecting every moment to hear mother scream out. She looked around and mother was close by the dog and stepped right over her. She was so frightened she said: "O, Mary, how did you get by that dreadful dog of Ben Crout's?"

Mother was wrothy, and said, "I didn't stop to think about that dog," and passed on. And this was the wonder to everybody around. It was the great talk of the day all about the country,

Page 35

how that Sam Berry's wife had passed Ben Crout's blood-hound and was not hurt. Then they began to say she must have had some kind of a charm, and they were shy of her. Ever after that nobody, black or white, troubled Sam Berry's wife. It was no charm, but was God's wonderful deliverance.

About two years or more after this, the papers were full of notices of a very valuable slave who had run away. A heavy reward was offered. He had by God's mercy got to us, and by moving the poor fellow from place to place he had been kept safe for about two weeks, as there was no possible chance for father or any one to get him away, so closely were we watched. My father was a very early riser, always up and out about day dawn. Our house stood in the valley between two hills, so that the moment you struck the top of the hill, either way coming or going, you could see every move around our house. Just on the opposite side of the road there used to stand two large chestnut trees, but these had been blown down by a great storm some time before, so there was no screen to hide the house from full view. This morning, while out in the yard feeding the pigs, he saw four men coming on horseback. He knew they were strangers. He could not get in the house to tell mother, so he called to her and said: "Mother, I see four men coming; do the best you can."

She must act in a moment without being able to say a word more to father. The poor slave man was upstairs. She brought him down and put him between the cords and straw tick. As it was early in the morning her bed was not made up. In the old-fashioned houses in the country we did not have parlors. The front room downstairs was often used as the bed-room. My little brother, two years old, slept in the foot of the bed. The men rode up and spoke to my father. He was a very polite man. "Good morning, gentlemen, good morning, you are out quite early this morning."

"Yes, we are looking for a runaway nigger." Just then my father recognized the high sheriff as Mr. E., who was formerly his young master. "Why, is this is not Mr. E.?"

"Yes, Sam, didn't you know me?"

My father made a wonderful time over him, laughed heartily and said: "What in the world is up?"

"Do you know anything about this runaway?"

Another spoke up and said: "We have a search warrant and

Page 36

we mean to have that nigger. We want to know if you have him hid away."

"Well," father said, "if I tell you I have not, you won't believe me; if I tell you I have, it will not satisfy you, so come in and look."

He didn't know a bit what mother had done, but he knew she had a head on her, and he could trust her in an emergency. The men hesitated and said: "It is no use for us to go in, if you will just tell us if you have him or know anything about him." And father said: "You come in, gentlemen, and look."

They said, "We have heard your wife is the devil," and then, speaking very nicely, "You know, Sam, we don't want any trouble with her, you can tell us just as well."

"No, gentlemen, you will be better satisfied if you go in and see for yourselves."

Just then mother, in the most dignified and polite manner, threw open the door and said: "Good morning, gentlemen, come right in." So they laughed heartily. Two dismounted and came in, went upstairs, looked all about while one looked in the kitchen behind the chimney, in the pot closet; and my mother went to the bed and threw back the cover (she knew what cover to throw back, of course,) there lay my little brother. She said: "Look everywhere, maybe this is he?"

"My! Sam," one of them said, "here is a darkey, what will you take for him?"

"No, you have not money enough to buy him," father said. Then mother said: "Now, gentlemen, look under the bed as well; you haven't examined every thing here," and they laughed and ran out and said: "Well, Sam, we see you haven't got him."

And father said: "Well, now you are better satisfied after you have looked yourselves." So he didn't tell any lie, but he had the darkey hid just the same!

They mounted their horses and went off full tilt to York. We children were sharp enough never to show any sign of alarm. Poor me, my eyes felt like young moons. The man was safe. After they had got away, mother got the poor fellow out, and he was so weak he could scarcely stand. He trembled from head to foot, and cried like a child. Poor fellow, he thought he was gone, and but for my noble mother he would have been. We soon got him off to Canada, where, I trust, he lived to thank and praise God, who delivered him from the hand of his masters.

Page 37

I can't tell just how long it was after this occurrence, but it was in harvest time. My father had got home from work and was sitting out in the front yard resting himself; it was just beginning to get dusk. We children were all around playing. A tall, well-built man came up to the fence. Father said: "Good evening, my friend." The poor man trembled, and said: "I don't know if you are a friend or a foe, but I am at your mercy."

"Don't fear," said father, "you are safe." Then he sat on the fence a while and began to tell his sad story. His feet had become so sore he could not travel. He had come away from New Orleans. He said his master owned a large sugar plantation and he was one of the head molasses boilers. His master was a very passionate man, and had threatened several times to sell him because he was a Christian and would pray, but he was a valuable man and so he held on; but he had committed a great offense this time. He said he was very tired, and, something he never did in his life before, he fell asleep from sheer weariness, and so burnt many. hogsheads of molasses, and this so enraged his master that he determined to sell him. He had a wife and three children, if I remember correctly. His master had him handcuffed and put in the cellar under the house, till the Georgia traders came. When the money was paid they generally had a great time drinking and gambling. He said he could not get to see his wife. O, how he prayed all day and all night. His young mistress, whom he had often nursed when she was a little child and whom he used often to carry about from place to place, was very much attached to him, as was frequently the case. She had been away North to school and was a Christian, and that may explain what followed. She was home from school just at this time, and like Queen Esther, when pleading for her people, she was made queen just in time. The evening before the morning he was to be taken away they were having a good jollification time. She waited till they were all full of excitement, and being a great favorite of her father's she managed to get the keys of the cellar and went in and unlocked his handcuffs and made him swear to her on his knees that if they ever caught him he would never betray her. Then she told him which way to go, to follow the North Star, which most of the slaves seemed to understand and travel by. She gave him a little money and something to eat. He prayed for God's blessing on her, and told her he would die if he was taken, but would never

Page 38

betray her; so he would. I shall never forget how he cried as he told this story to my father. He said he had traveled for three weeks, and after his food was all gone he lived on berries, blackberries were just ripe. He would lie by in the day and travel at night; kept in the woods, never traveled in day time, only when it would rain. We soon took him in and got water and bathed his feet. Mother got him a good supper. O, how the poor man ate; he was nearly starved. We kept him about two weeks, and then succeeded in getting him off to dear old Canada. O, how much this poor slave man went through for only the liberty of his body, and yet how few there are that are willing to make any sacrifice to secure the freedom of souls that Jesus so freely offers, for if the Son shall make you free then are ye free, indeed. Thank God, these days of sadness are past, never to be repeated, I trust. The poor man, I suppose, never heard of his wife and children, for this was years before the war and it was not likely they ever met on earth again, but I trust they will meet beyond the river where the surges cease to roll.

Page 39

CHAPTER IV.

MOVING FROM LOWE'S FARM.—MARRIAGE.—CONVERSION.

After twelve years on John Lowe's farm, my father had an offer from a man named John Bear; it was between five and six miles from where we were. It was a small farm and my father had a better chance to help himself. He used to work a good deal in Strausburg then. Dr. Bull and his brother, Rev. Wesley Bull, lived in Strausburg. My oldest brother lived with the doctor a long time and took care of his horses. The doctor married a Miss Jane Berry, daughter of old Colonel Berry, of Baltimore. They first settled in Strausburg. I lived with them some time. How well I remember the old Colonel; he used to come to visit them, and was very kind to me. Would often speak to me about my soul's interest, but I was young and did not pay much attention at the time, but I never forgot it. After a time Dr. Bull moved to Baltimore, and Dr. Turner, who married Miss Julia Berry, Mrs. Bull's sister, lived in Strausburg, then I lived with Dr. Turner. How well I remember Dr. and Mrs. Turner. They were very fond of Maryland biscuit, and though I was young, I had the reputation of making the best Maryland biscuit and frying the nicest chicken of anyone around there, and the doctor used to say "Amanda can beat them all making Maryland biscuit and frying chicken." My! how it did please me! Somehow it is very encouraging to servants to tell them once in a while that they do things nicely; it did me good. I would almost kill myself to please them, and Doctor Turner's mother, dear Mrs. Flynn, what a good woman she was! She gave me the first Testament I ever had and used to come into the kitchen and read to me sometimes. She came several times on a visit to see Dr. and Mrs. Turner. After a time Dr. Turner moved back to Baltimore again, I went with them. It was my first time in Baltimore. We got in at night and I remember how I had never seen fine lights glittering in drug stores before, and as

Page 40