Parkway Development and the Eastern Band of Cherokees, part 1 of 3

By Anne Mitchell Whisnant

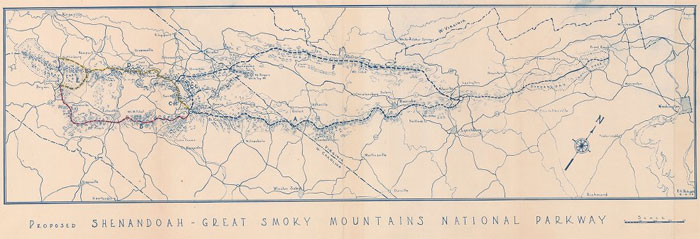

Proposed Shenandoah - Great Smoky Mountains National Parkway, June 4, 1934

North Carolina State University

The most complicated early controversy over the Parkway arose at Cherokee, North Carolina. There, North Carolina and federal officials struggled for five years in the 1930s to convince the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians to grant a right-of-way for the Parkway's final fifteen miles across their lands, known as the Qualla Boundary.

At Cherokee, the Parkway right-of-way question became entangled in a thicket of other issues related to New Deal-era federal Indian policy, managed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, a sister agency to the National Park Service within the Department of the Interior. For North Carolina State Highway Commission staff, securing the Cherokee right-of-way brought an unanticipated lesson in the complexities of Indian identity, and an unwanted foray into the confusing arena of federal Indian policy. For the Eastern Band, the fight over the Parkway provoked an intense internal battle over the best route to economic and cultural survival in twentieth-century America.

The intermingling of all of these agendas illustrated, perhaps better than any other episode in the Parkway's early history, that the park’s meaning and impact, the politics of its advent, and the sources of its support and opposition depended greatly upon the local context.

The Legal and Economic Status of the North Carolina Cherokees in the 1930s

In the 1930s, when the Great Smoky Mountains National Park opened at their doorstep and the Blue Ridge Parkway plans were announced, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians controlled nearly sixty thousand acres, most of which were in Swain and Jackson counties in western North Carolina. Some 2,200 Indians called the reservation (the main part of which is named the Qualla Boundary) home.

The Depression battered the Cherokees, whose economy was already foundering following the collapse of the lumber industry, many of whose bereft former employees now eked out a living through subsistence farming. But the tribe's limited base of arable land (estimated at less than fifteen percent of the reservation's acreage in 1900 and possibly as little as five percent by the 1930s) precluded farming from providing a sufficient livelihood for most members. Sale of timber cut on the reservation generated some funds, and the Tribal Council of the Eastern Band provided relief money to those hardest hit by the economic disaster, but a new source of tribal income was clearly necessary.[1]

Tourism seemed plausible to many, especially with the recent opening of the new national park (with which the reservation shared a boundary) and the ongoing legacy of the annual Cherokee Fair (held every fall since 1914), but the Cherokees disagreed with each other about whether the federal government could (or should) be an ally in building that industry.[2]

These disagreements were exacerbated by the tribe’s complicated legal history. The Eastern Band’s members were descended from a small band of Cherokees who had avoided the great removal and Trail of Tears of the 1830s. This group had subsequently purchased several tracts in western North Carolina, which the state had helped them to retain in the years after the Civil War. The Indians' legal standing solidified in 1889, when Chief Nimrod Jarrett Smith obtained a state charter organizing the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians as a corporation. This status allowed the Band to conduct business, take cases to court, and act as a political unit. The charter provided for tribal self-government via a tribal council and a Principal Chief and Vice-Chief. Simultaneously, the Band received federal recognition as a tribe, which meant that the Bureau of Indian Affairs exercised some control through an agent stationed in the town of Cherokee.[3]

This dual recognition (by the state as a corporation and by the federal government as a tribe) meant that the state and the national governments both had authority in certain areas, and jurisdictional lines sometimes blurred. The fact that the Indians owned their land as a corporation and conducted their business through an elected tribal council also complicated questions of governmental power over their property and, in practice, granted the tribe considerable autonomy.[4] This autonomy set the stage for the Band's resistance to the Blue Ridge Parkway.

The Indian New Deal

The controversy over the Parkway right-of-way at Cherokee, North Carolina, erupted in the midst of an intense debate among Native Americans over the Indian New Deal. This set of policies, initiated by new Indian Commissioner John Collier and anchored by the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act (or IRA, also known as the Wheeler-Howard Act), represented what many viewed as a progressive revolution in federal management of Native American affairs.

Departing from an emphasis on Indian cultural and economic assimilation and individualized property ownership that had dominated federal policy (and severely eroded Native Americans’ land base) since the 1887 Dawes Act, Collier’s policies encouraged tribal governmental autonomy and tribally based economic development; revitalized artistic, linguistic, and religious traditions; and provided means for a renewed commitment to communal land ownership.[5]

Already working under a system set in place by a North Carolina charter similar to that proposed by the IRA, the Eastern Band of Cherokees voted their general approval of the IRA in mid-1934. Increasingly, however, a more acculturated faction within the Band objected that by encouraging "tribalism," the Indian New Deal discouraged Indians' individualism and undermined their ability to assimilate and survive in a white-dominated world. Nationally, Indian opposition to the Indian New Deal coalesced in the American Indian Federation (AIF). Formed in 1934, AIF was pan-Indian, assimilationist, often right-wing, anticommunist, and anti-Bureau of Indian Affairs. The AIF eventually attracted some four thousand members.[6]

Among the Eastern Cherokees, the leading spokespersons against both the Indian New Deal and the Blue Ridge Parkway were AIF members Fred and Catherine Bauer. Throughout the 1930s, the Bauers campaigned against the IRA. When the proposal for the Parkway came along, they viewed it through the lens of their opposition to the IRA and their suspicion of the overall agenda of the New Deal.[7]

The Advent of the Parkway at Cherokee

When it was first proposed, the Blue Ridge Parkway appealed to the Eastern Band of Cherokees because it appeared to address pressing travel problems on the reservation. Existing highways radiating out of the Qualla Boundary led only to the north (to Gatlinburg) and west (to Bryson City). But there had already been plans in place since the early 1930sfor a state highway going east from Cherokee towards Waynesville and Asheville. Indeed, the tribe had already granted a sixty-foot right-of-way for this road through the relatively heavily populated Soco Valley section, one of the mountainous reservation's two or three flat tracts suitable for farming and development. When plans for the Parkway were developed, the state and tribal officials initially assumed it would simply replace the plans for the state highway, and the Tribal Council agreed in January of 1935 to grant a 200-foot right-of-way for the Parkway.[8]

The Cherokees quickly became concerned about rumors that the Parkway would take much more than two hundred feet of right-of-way and that it would not be the usable, accessible highway they wanted. In late February of 1935, Cherokee activist Fred Bauer, who himself lived in the Soco Valley, rushed to Washington to deliver to Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Collier and National Park Service (NPS) Assistant Director A. E. Demaray an anti-Parkway petition signed by 271 members of the Band that asserted that the Parkway “will not benefit us, and will take out of cultivation much land needed by the Indians.”[9]

Collier quickly realized that the Bauer opposition could split the Eastern Band and thwart all federal initiatives under way on the reservation. He urged officials at NPS and the North Carolina State Highway Commission to move cautiously in negotiating for the right-of-way. In mid-March, he instructed Park Service Director Arno B. Cammerer that no work on the Cherokee Parkway sections should begin until the matter was resolved to the satisfaction of the Eastern Band. By mid-April of 1935, NPS and the Highway Commission had halted work on the fifteen-mile section of the Parkway across Cherokee lands.[10]

Bureau of Indian Affairs and NPS leaders planned a carefully worded message to the tribe from Interior Secretary Harold Ickes to inform them about the Parkway plans and to reassure them that the government would not coerce them to accept a highway they did not want. "I have been told," Ickes wrote, "that the Cherokee Tribe is not in favor of the proposed location. If you do not want the road to be built where the National Park Service desires it to go, it will not be built."

Ickes then confirmed the fears of Fred Bauer and his wife Catherine: the Parkway's right-of-way and easements would take or control an area nearly one thousand feet wide in many spots, consuming much more valuable Soco Valley farmland than originally expected. Easement restrictions would prohibit commercial development alongside the road, and adjoining residents would not have direct access to the new highway. Nevertheless, Ickes projected the Parkway would bring increased tourist traffic to Cherokee trading posts and their planned hotel and boost sales of Indian-made products, and explained the payment that landowners would receive for lost homes and property. He reiterated that "this entire matter will be decided by the Cherokee Tribe."[11]

This was not the highway Soco Valley residents needed or expected. While approximately half of the proposed route from Soco Gap to Cherokee snaked through difficult, hilly terrain, the last five or six miles pierced the rich, level bottom lands along Soco Creek, which was bounded on either side by sharply rising slopes. A thousand-foot right-of-way for this section of the Parkway would have swallowed the valley whole. The tribal council met in emergency session in June of 1935 and rescinded its approval of the right-of-way.[12]

2. Finger, Cherokee Americans, 32, 67-74, 84.

3. Finger, John R. The Eastern Band of Cherokees, 1819–1900. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1984.; Perdue, Native Carolinians, 36-44; and Finger, Cherokee Americans, xi, 9.

4. Finger, Cherokee Americans, 9-10.

5. On the Indian New Deal, regionalism, and the Eastern Band, see Prucha, Francis Paul. The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986.; Taylor, The New Deal and American Indian Tribalism; Philp, John Collier's Crusade for Indian Reform, 1920-1954; Kelley, The Assault on Assimilation; Dorman, Revolt of the Provinces; Watkins, Righteous Pilgrim, and Finger, Cherokee Americans.

6. Finger, Cherokee Americans, 80, 84-85; Weeks, Charles J. “The Eastern Cherokee and the New Deal.” North Carolina Historical Review 53 (1976): 311-319; Hauptman, Laurence M. “The American Indian Federation and the Indian New Deal: A Reinterpretation.” Pacific Historical Review 52 (1983): 378-402.

7. Weeks, "The Eastern Cherokee and the New Deal," 311-319; Finger, Cherokee Americans, 84-91; Bauer, Fred B. Land of the North Carolina Cherokees. Brevard, N.C.: Buchanan, 1970.

8. EBCCM, 7 January 1935 meeting; Senate, Subcommittee of the Committee on Indian Affairs, Survey of Conditions, 20596, 20616, 20633; House, Committee on Public Lands, Establishing the Blue Ridge Parkway, 55, 61; Catherine A. Bauer to Capus M. Waynick, 20 October 1935, State Highway Commission, Right of Way Department, Blue Ridge Parkway Records, North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh (hereafter cited as SHCRWD), Box 15, North Carolina State Archives; See map of North Carolina in Rand McNally Road Atlas, 1936, 62-63 and Hill, "Cherokee Patterns," 453, 457-58, and the North Carolina Atlas & Gazetteer. There is some confusion about exactly what action the Council took at its January meeting. Council minutes seem to indicate that they "granted" the right-of-way. Catherine Bauer reported, however (Bauer to Waynick, 20 October 1935, SHCRWD, Box 15, North Carolina State Archives) that the Council simply granted state and federal officials the right to survey for a right-of-way for the Parkway on the reservation, a much more cautious move. At any rate, the January council was clearly much more amenable to the possibility of the Parkway coming to the Reservation than later councils would be. See also Finger, Cherokee Americans, 78-79; E. B. Jeffress to Theodore E. Straus, 1 June 1934, RG 79, Record Group 79 (National Park Service), Central Classified Files, 1933–49, Entry 7B, “National Parkways-Blue Ridge,” National Archives II, College Park, Maryland (hereafter cited as CCF7B), Box 2711.

9. Catherine A. Bauer to Capus M. Waynick, 20 October 1935, SHCRWD, Box 15, North Carolina State Archives; John Collier to Arno B. Cammerer, 21 February 1935, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2734. From RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2734: John Collier to Arno B. Cammerer, 21 February 1935; and A. E. Demaray to Thomas C. Vint, 23 February 1935. On the petition, see Senate, Subcommittee of the Committee on Indian Affairs, Survey of Conditions, 20596-20597. I have been unable to locate a copy of this petition to review directly. See also Catherine A. Bauer to Capus M. Waynick, 20 Oct. 1935, SHCRWD, Box 15, North Carolina State Archives; and Senate, Subcommittee of the Committee on Indian Affairs, Survey of Conditions, 20596-20600, 20614-17.

10. From RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2734, see John Collier to Arno B. Cammerer, 4 March 1935; and A. E. Demaray to John Collier, 18 April 1935.

11. Harold L. Ickes, "Message to the Cherokee Tribe," 20 May 1935, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2734.

12. House, Committee on Public Lands, Establishing the Blue Ridge Parkway, 66; Finger, Cherokee Americans, 75-76; Harold W. Foght and Jarrett Blythe to Harold L. Ickes, 24 June 1935, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2734, NARA II; Catherine A. Bauer to Capus M. Waynick, 20 October 1935, SHCRWD, Box 15, North Carolina State Archive.