Reinterpreting the Caudill Cabin: Community, Mobility, and Tragedy in Rural Appalachia

By Cassandra McGuire

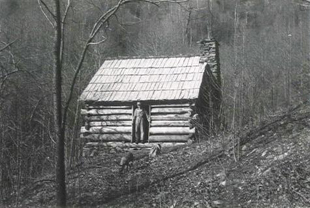

From the Wildcat Rocks overlook at milepost 241 of the Blue Ridge Parkway (BRP) in Alleghany County, North Carolina, the Caudill Cabin can be spotted fifteen hundred feet below. This is the only view that most Parkway visitors get of the cabin, since it can only be reached via a 3.3 mile hike. From the vantage point of Wildcat Rocks, the Caudill Cabin appears to be a small speck of civilization in a vast wilderness. The first Blue Ridge Parkway Superintendent, Stanley Abbott, referred to the cabin an example of the “extreme isolation of mountain folk,” a statement in line with the National Park Service’s longtime interpretive goal of emphasizing the cabin’s remoteness from the civilized world.[2]

Since the National Park Service (NPS) acquired the cabin in 1938, Blue Ridge Parkway interpreters have repeatedly misrepresented and oversimplified its history, using the cabin to perpetuate pervasive and longstanding American stereotypes about the isolation and pioneer culture of Appalachian people. In truth, the Caudill Cabin and its former inhabitants were part of a larger story of community, geographic mobility, and family tragedy.

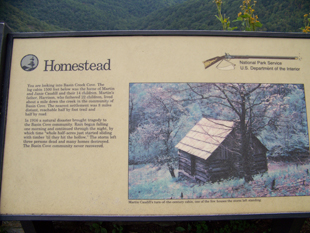

In recent years, NPS interpretive efforts at the Caudill Cabin have improved: the current interpretive sign at the site places much more emphasis than its predecessors on both the community that once surrounded the now lone Caudill Cabin and the 1916 natural disaster from which the Basin Cove community never fully recovered. There is still a need, however, to share a richer, more complex history of the Caudill Cabin and the Basin Cove community with the public.[3]

“The Prettiest Bottom Land You Ever Seen”: The Basin Cove Community[4]

When the Caudill family first settled in Basin Cove in the late nineteenth century, the landscape looked very different than it does today[5]. According to one long-time resident of the area interviewed in 1975, Basin Cove “was a beautiful place back years ago…. [There were] big fields, flat. In there, at that little cabin you can see is what you call a wheat field, was eighteen acres and you could drive a car all over the top of it…at the foot of the mountain there, they was around seventy-five acres, just the prettiest bottom land you ever seen.” The people of Basin Cove raised wheat, corn, potatoes, beans, and other vegetables on their farms, both to feed themselves and to sell in nearby Wilkesboro, Mt. Airy, or Winston. If they needed items they could not produce for themselves, they traveled to nearby Abshers, where a post office and general store were located.[6]

A central landmark in the community was Basin Creek Union Baptist Church, founded circa 1888 - 1889 – a simple clapboard structure where local residents came together to socialize and worship. There were services each week on Saturday and Sunday and a revival meeting in August. Baptisms, communions, and foot washings were also held once each year. The church continued to be used for religious services until about 1930, when there was a falling out among church members. The building was then repurposed (somewhat ironically) for use as a dance hall.[8]

This same clapboard structure also served as the community’s schoolhouse. Children living in Basin Cove could attend Basin Creek School, which was open for about four months each year. The school had about fifty students at any given time although there was only one teacher. Sometimes, when they had free time, boys and girls living in the area would meet at the school and hold debates.[9]

Clearly, the Basin Cove community was not isolated, having its own church and school as well as connections with other towns nearby. It was, moreover, one of many such communities in Appalachia at the time. Nevertheless, Barry M. Buxton, the author of the NPS’s 1988 Brinegar Cabin Historic Resource Study, claimed that mountain people in general had “but occasional contact even with their neighbors” and were prevented from “any extensive travel beyond the local valley or area” by “steep mountain barriers.”[10]

This generalized interpretation of mountain life—prevalent in both scholarly and popular writing from the late nineteenth century into the 1970s—does not accurately describe the residents of Basin Cove, who frequently met together in public spaces and traveled to surrounding towns to carry out business. The themes of community and mobility become even more evident when one examines the history of the Caudill family from which the cabin takes its name.

View The Geographic Mobility of the Caudill Family and other Basin Cove Residents in a larger map

“Sort of Like a Pioneer”: The Caudill Family [11]

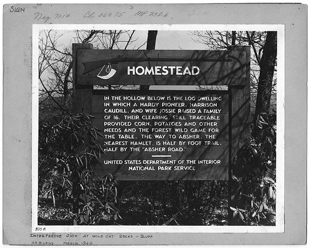

When the NPS first began to interpret the Caudill Cabin circa 1940, the agency attributed the structure to the wrong Caudill: Harrison Caudill, one of the earliest settlers of Basin Cove. The 1940s interpretive sign advised Parkway visitors that “In the hollow below is the log dwelling in which a hardy pioneer, Harrison Caudill, and wife Jossie raised a family of 16. Their clearing, still traceable, provided corn, potatoes, and other needs and the forest wild game for the table. The way to Absher, the nearest Hamlet, is half by foot trail, half by the ‘Absher Road.’” Even if the sign’s most serious error is disregarded (Harrison Caudill never lived in the Caudill Cabin), this attempt at interpreting the Caudill Cabin and the lives of its inhabitants oversimplified the story in order to cast the Caudill family as stereotypical mountain “pioneers.” In doing so, it lost much of the truth – and the intriguing details – of the Caudills’ lives.[12]

As the current interpretive sign correctly states, the Caudill Cabin was actually not built by Harrison Caudill, but by his son Martin Caudill. He built it in 1890, likely as his first home. It did not, however, serve as a home for two adults and fourteen children. While Martin and his wife Janie ultimately raised a very sizeable family, only the first six – Famon, Bessie, Harrison, Lonnie, Phoebe, and Cornelius – were born while the family was living in the Caudill Cabin. In addition to building the cabin, Martin Caudill cleared approximately ten to fifteen acres of land for farming and constructed several outbuildings.[14]

To a considerable degree, the Caudills were a self-sufficient family. According to Martin Caudill’s niece Ruby Caudill Adams, they “grew most of what they ate, sort of like a pioneer.” Besides growing crops and raising livestock, the Caudill men hunted wild game, including rattlesnakes, mudturtles, squirrels, and possums, and the Caudill women made clothes and quilts from the wool and flax produced on their farm.[15]

Harrison Caudill, meanwhile, was far more than a “hardy pioneer.” In fact, he was somewhat of an enigma. Although he was primarily a farmer, he reportedly supplemented his income by trapping and bootlegging, and he was known throughout the community for making shoes. Caudill was also certainly known for his family life: he had twenty-two children by two sisters, having married the second after the death of the first. Even more remarkable was the fact that half of the children were boys, half were girls, half were red-heads (like their father), and half were brunettes (like their mothers). Even the NPS seems to have been impressed by Harrison’s fecundity, noting it (albeit with the wrong number of children) on the 1940s Caudill Cabin interpretive sign. The interpreters’ decision to publicize this information, however, was likely motivated by more than a desire to shock visitors. By invoking the image of Harrison’s sizeable family crowded under the tiny Caudill Cabin roof, BRP interpreters reinforced yet another stereotypical trait of Appalachian people: poverty. Ironically, Harrison Caudill may well have been a wealthy man: he is said to have had a two-story home, considerable land-holdings, and a number of tenant farmers working on his land.[16]

Unlike the pioneers portrayed in Parkway literature, who stayed in one place their entire lives without knowledge of the outside world, the Caudills were geographically mobile. Sometime after the birth of their son Cornelius in 1906, Martin and Janie Caudill moved their family away from Basin Cove and the Caudill Cabin to Konnarock, Virginia, where the burgeoning lumber industry was creating numerous jobs and a thriving local economy. The largest lumbering operation in Konnarock was the Hassinger Lumber Company, founded by M. L. Hassinger and his three sons in 1903. The company operated until 1928, producing between fifteen and eighteen million board feet of lumber each year. It is likely that the Hassinger Lumber Company employed Martin Caudill, as the 1910 census of Washington County, Virginia, identifies Caudill as a laborer at a logging camp. Some of Caudill’s sons also found employment in Konnarock’s lumber industry: Famon (age 15) worked as a laborer alongside his father, and Famon’s younger brothers Harrison (age 10) and James (age 8) were paid to cut wood.[17]

The Caudills remained in Konnarock for several years before eventually returning to Basin Cove in the winter of 1915. Instead of moving back into the Caudill Cabin (which may or may not have had other occupants by this time), however, they took up residence in another house known as the “Metti place.” This home, not the Caudill Cabin, was where Martin Caudill’s family was living during the summer of 1916 when disaster struck Basin Cove.[18]

“Big Mountains Just a Coming in Towards You”: The Flood of 1916[19]

In mid-July of 1916, a devastating flood ravaged the mountains of North Carolina, including the Basin Cove region. An article in the Wilkes Patriot, published in nearby Wilkesboro, described the horror of the flood for mountain communities: “the everlasting hills and mountains,” it said, “were not able to withstand the awful fury of the storm, for while the lowlands were being lashed and torn by the raging torrent, great landslides were ripping the very heart out of majestic mountains and hills in many places.”[20]

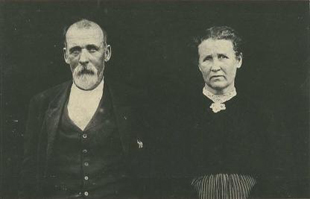

Edna Caudill Brooks, one of Martin Caudill’s daughters, was six years old at the time of the flood. During a 1976 interview, she recalled: “You could see them big mountains just a coming in towards you and the water and the mud and the trees and my daddy says, ‘Lord let’s all get out of here, we’re going to be washed away!’” Martin and his wife Janie gathered their children together and fled further up the mountain, where they found shelter with their neighbors John and Caroline Brinegar. The Caudills stayed with the Brinegar family for the next three days.[21]

John and Caroline Brinegar, ca. 1910s. They took the Caudill family into their home during the 1916 flood.[22]

North Carolina State Archives

Unfortunately, not all of Martin Caudill’s family arrived at the Brinegar cabin that night. Martin’s oldest son, Famon, had found work in Green Cove, Virginia, and he had left his young wife, Alice, behind in Basin Cove. Shortly before the storm had started, Famon’s nine-year-old brother, Cornelius, had walked to Famon’s cabin near Basin Creek to stay with Alice (who was pregnant at the time) and Alice’s mother, Wadie Adams. The flood waters ripped Famon’s cabin from the ground and washed it away, drowning everyone inside. Regrettably, news of the tragedy did not reach Famon until he returned home two weeks later, only to discover that his wife, brother, and mother-in-law had already been buried and his home had been lost. [23]

Although the Caudill Cabin survived the flood, most of the other houses and the fertile farmland of Basin Cove were washed away. Furthermore, large numbers of livestock (including Martin Caudill’s hogs and cows) were lost to the storm. This complete desolation caused many Basin Cove families, including the Caudills, to abandon the area. Edna Caudill Brooks remembered leaving the cove on August 29, 1916, just over a month after her brother Cornelius’s body was buried. Two neighbors, John Brinegar and Gaither Taylor, helped them move their belongings. The Caudills spent one night in West Jefferson, North Carolina, before once again settling down in Konnarock, Virginia. Although Martin Caudill did return to North Carolina years later, he did not return to Basin Cove; he instead chose to make his home in the New Life community of Wilkes County, where he remained until his death.[24]

“Should Ought to be Called the Caudill Park”: The Arrival of the Parkway[25]

By the time that the Parkway came to Basin Cove in the 1930s, the region was largely deserted. According to Elder W. M. Hamm, one of the former ministers of Basin Creek Union Baptist Church, there were fifty-two families in Basin Cove in 1916 and only eight remaining when the Parkway was built. (Leo Collins, a Parkway maintenance supervisor knowledgeable of the Basin Cove area, gave a more modest estimate of twenty families living in the community at its peak). Although few of the earlier residents remained in the area, the land still belonged to private owners and had to be acquired by the NPS. Many of the Basin Cove properties which were taken for the Basin Cove properties which were taken for the BRP were formerly Caudill lands, sparking one Caudill descendant to retort that “the Doughton Park should ought to be called the Caudill Park.”[26]

The Caudill Cabin was the only structure from the old Basin Cove community still standing when the Parkway was constructed, and it had been abandoned since 1918. The cabin was acquired by the NPS in 1938, and Abbott quickly deemed it “one of the finest, if not the finest, example of pioneer cabins” along the route of the Parkway. In 1953, the Caudill Cabin was included on a “Pioneer Culture Interpretation Map” produced for the BRP, clearly illustrating the cabin’s role in the NPS’s plan to emphasize the perceived isolation and primitive lifestyles of mountain people.[27]

In more recent decades, the focus of BRP interpreters has begun to shift with regard to the Caudill Cabin site. A 1973 National Register of Historic Places nomination form completed for the Caudill Cabin by Parkway historian F. A. Ketterson, Jr., reveals that the BRP had started emphasizing the cabin’s connection to the tragedy of the 1916 flood rather than simply identifying it as a pioneer homestead. Furthermore, in the mid-1970s, a joint effort was made by the BRP and the History Department of Appalachian State University to learn more about the Basin Cove community through oral histories. Several interviews were undertaken, and transcripts were made to “assist the Parkway staff interpreters in presenting the history of this area to the general public.” This project may in part account for the current Caudill Cabin interpretive sign’s increased accuracy and emphasis on community. The idea of “pioneer isolation,” however, is still evident at the Caudill Cabin. This interpretation must be more actively counteracted in order for the historical fact of the cabin’s location within a vibrant mountain community to overcome the sense of isolation imparted by the view from Wildcat Rocks.[29]

2."Appendix Q: Wayside Exhibit Plan of Blue Ridge Parkway, Exhibit 081," in Barry M. Buxton, Brinegar Cabin Historic Resource Study, National Park Service, U.S. Department of Interior, June 16, 1988; Debbie Northrop, “Caudill Cabin, B100, MP 241.1" memorandum, April 14, 2000, Blue Ridge Parkway Buildings Files, Engineering and Technical Services Division, Asheville, North Carolina; "The Caudill Cabin," part of a "Historic Structure Report," prepared by John J. Palmer, May 10, 1968, Blue Ridge Parkway Buildings Files, Engineering and Technical Services Division, Asheville, North Carolina.

3. Sandra McGuire, Caudill Cabin Interpretive Sign digital photograph, September 22, 2012.

4. Interview with Harrison Caudill in Carl A. Ross, ed., Basin Cove: An Oral Record (Boone: Appalachian State University, 1983), p. 16.

5. Census records were not helpful in establishing a more exact date for the Caudills arrival in Basin Cove, as no exact addresses or references to “Basin Cove” are given. Instead, residents are listed according to their township. The Caudill family is listed as living in another area of Alleghany County in the 1870 census but were listed as living in the correct township (though not necessarily in Basin Cove) as of 1880.

6. Ross, ibid., p. 1; interview with Harrison Caudill, ibid., pp. 16, 22, 24.

7. Caudill Cabin photograph, 1940s, from Driving Through Time: The Digital Blue Ridge Parkway.

8. Interview with Elder W. M. Hamm, ibid., pp . 57-60; interview with Harrison Caudill, Jr., ibid., pp. 82-83, 85; interview with Edna Martha Ann Caudill Brooks, ibid., p. 52.

9. Interview with Brooks, ibid., p. 53; interview with Harrison Caudill, Jr., ibid., p. 82; interview with Harrison Caudill, ibid., pp. 21-23; interview with Hamm, ibid., pp. 63-66.

10. Buxton, Brinegar Cabin Historic Resource Study, pp. 4-5.

11. Interview with Ruby Caudill Adams in Ross, ed., Basin Cove, p. 10.

12. A. S. Burns, Interpretive Sign at Wildcat Rocks photograph, March 1946, from Driving Through Time: The Digital Blue Ridge Parkway.

13. Burns, Interpretive Sign at Wildcat Rocks photograph.

14. F. A. Ketterson, Jr., “National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form for Federal Properties, Martin Caudill Cabin," May 3, 1973, in the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives, Asheville, North Carolina (Record Group 5, Series 49, National Survey of Historic Sites-Proposed, Box 68); interview with Harrison Caudill in Ross, ed., Basin Cove, p. 15; interview with Spencer E. Caudill, ibid., p. 33.

15. Interview with Adams in Ross, ibid., p. 10; interview with Harrison Caudill, Jr., ibid., p. 81.

16. Interview with Harrison Caudill, Jr., in Ross, ed., Basin Cove, p. 81; interview with Harrison Caudill, ibid., pp. 23-24; interview with Spencer E. Caudill, ibid., pp. 32, 35; Burns, Interpretive Sign photograph.

17. Interview with Brooks, ibid., p. 51; Luther C. Hassinger, “The Lumber Industry in Southwest Virginia,” in The Historical Society of Washington County, Virginia, Publications, Series II, No. 4, Spring, 1967; “Year: 1910, Census Place: Holston, Washington, Virginia, Roll: T624_1651, Page: 12B, Enumeration District: 0118,” accessed via Ancestry.com.

18. Interview with Brooks in Ross, ed., Basin Cove, p. 52; interview with Harrison Caudill, ibid., p. 17.

19. Interview with Brooks, ibid., p. 54.

20. “Flood Wrought Great Damage,” The Wilkes Patriot, July 27, 1916, p. 1, North Carolina Collection.

21. “Year: 1920, Census Place: Walnut Grove, Wilkes, North Carolina; Roll: 7625_1329; Page 10A; Enumeration District: 188, Image: 633,” accessed via Ancestry.com; interview with Brooks in Ross, ed., Basin Cove, pp. 51, 54.

22. Reproduction of Martin and Caroline Brinegar photograph, 1910s, from Driving Through Time: The Digital Blue Ridge Parkway.

23. “Wilkes County Witnesses Largest Flood in Its History,” The Wilkes Patriot, July 20, 1916, pp. 1, 3, North Carolina Collection; interview with Brooks in Ross, ed., Basin Cove, p. 51; Barbara Johns Groeger, Out on a Limb (El Cajon, CA: Photo Arts, Inc., 1960), p. 63; Buxton, Brinegar Cabin Historic Resource Study, pp. 68-69.

24. Interview with Harrison Caudill in Ross, ed., Basin Cove, p. 17; interview with Brooks, ibid., pp. 51-54.

25. Interview with Harrison Caudill, ibid., p. 15.

26. Interview with Hamm, ibid., p. 58; interview with Leo Collins, ibid., p. 3; interview with Harrison Caudill, ibid., p. 15.

27. Ketterson, “National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form”; "The Caudill Cabin”; Lewis and United States Department of the Interior, “Pioneer Culture Interpretation” map, 1953, from Driving Through Time: The Digital Blue Ridge Parkway.

28. McGuire, Caudill Cabin Interpretive Sign digital photograph.

29. Ketterson, “National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form”; Ross, ed., Basin Cove; p. 1; McGuire, Caudill Cabin Interpretive Sign digital photograph

30. Caudill Cabin Photograph, 20th Century, from Driving Through Time: The Digital Blue Ridge Parkway.