Photographer Spotlight: Abbie Rowe

By Meghan Cunningham, Justin Hui, Samantha Leonard, and Jacqui Moskel

Edited by Anne Mitchell Whisnant

View Abbie Rowe's Blue Ridge Parkway photographs.

Abbie Rowe was a photographer for the National Park Service, and later for the White House. From 1930 to 1967, Rowe documented work by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the Washington D.C. area, five presidential administrations, the 1948 White House renovation, and various National Parks along the East Coast, including the Arlington National Cemetery, Great Falls Park, Greenbelt Park, and the Blue Ridge Parkway.

Rowe was born in Strasburg, Virginia, on August 24, 1905.[1] He began his career as a civil servant in 1930 with the federal Bureau of Public Roads, and in 1932 he transferred to the Office of Buildings and Public Parks, the forerunner of the National Capital Parks office of the National Park Service. While serving there as a guard and caretaker for the Roaches Run Waterfowl Sanctuary, Rowe began photographing birds at the sanctuary. His work soon impressed publishers, and he was invited to apprentice as a photographer with the Park Service. Rowe would eventually be promoted to a junior, and then senior, Park Service photographer.[2]

Picnic Group, Cumberland Knob,

Adults and children having a picnic at Cumberland Knob, milepost 217.5, section 2A on the Blue Ridge Parkway, June 1946. Photograph taken by Abbie Rowe. National Park Service photograph.

The Park Service initially assigned Rowe to take photographs of the work being done by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the greater Washington, D.C. area, which during the late 1930s and 1940s was being transformed into the city that we know it to be today. Rowe’s photographs document the construction of roads, general beautification projects, the restoration of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, as well as general maintenance and restoration on Fort Washington and Fort DuPont.[3]

Automobile and people standing at the overlook at Fox Hunters Paradise near mile post 218.6 in section 2A on the Blue Ridge Parkway, 1946. Photograph taken by Abbie Rowe. National Park Service photograph.

In a major reshuffling of the Executive Branch and expansion of the National Park Service under the Reorganization Act of 1933, President Roosevelt dissolved the Office of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital and placed the White House and other public buildings in the capital under the stewardship of the National Park Service.[4] Rowe soon benefited from the change and spent the majority of his career taking photographs for the White House, where he procured an assignment in 1941 after a direct appeal to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, whom he may have met briefly in the late 1930s. Like President Roosevelt, Rowe struggled with the crippling effects of polio. Understanding Rowe’s physical limitations, Mrs. Roosevelt advocated for his requested job change[5], and thus, Rowe remained in the employ of the National Park Service while photographing for five presidential administrations (Roosevelt, Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson) and many eastern national parks.

When Abbie Rowe first began acting in this capacity for President Roosevelt in 1941, he took pictures only of the president’s larger, more important activities outside of the White House.[6] These included official ceremonies, visits from foreign dignitaries, the announcement of the surrender of Japan that ended World War II, and many other state functions. But gradually he expanded his focus to what was taking place inside the White House, as well. Rowe began to take pictures of smaller ceremonies “that are part of the pomp and symbolism of the presidency,” such as pardoning Thanksgiving turkeys and welcoming groups of Girl Scouts.[7]

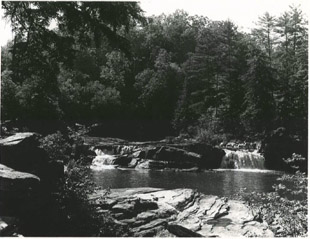

Upper falls at Linville Falls near milepost 316 on the Blue Ridge Parkway, June 1946. Photograph taken by Abbie Rowe. National Park Service photograph.

Rowe was part of an evolving photographer role that coalesced during the Lyndon Johnson presidency in the creation of the position of “Official White House Photographer” and was assigned to a single person. In Rowe’s time, however, photographers were hired on an as-needed basis from the National Park Service as well as from branches of the Armed Forces, in most cases from the Army or Navy.[8] Each picture taken by Rowe, and by every White House Photographer since, has helped to compile what has been termed a “photographic archive as part of a record for the ages.” President Clinton’s Official Photographer, Robert McNeeley, said his approach “was to not intrude on the history, but to capture it in a way so that people could have a sense of what’s going on and to not make them feel like it was being manipulated, it wasn’t posed, it was natural and candid.”[9]

Documenting the White House Restoration

While working for President Truman, Rowe’s largest responsibility was documenting the massive restoration of the White House from 1948 to 1952. In 1948, Truman noticed creaks and popping noises in the White House. A 1948 engineering report found the White House in bad condition due to an 1814 fire and damaging modifications performed from 1902 to 1927. Truman decided to gut the entire building – saving the exterior, but starting mostly from scratch on the inside. Once Congress approved the plans, Truman moved into the Blair House across the street for three years while the restoration was completed.[10]

Truman White House Restoration, 1948-1952,

Taken by Abbie Rowe and taken from the The White House Historical Association

Rowe was named the official photographer of the White House renovation and devoted himself almost entirely to documenting the restoration process. His work was displayed at the Truman Library in Independence, Missouri, as part of a 2002 exhibit entitled “The White House Revealed: Photos of the White House Renovation by Abbie Rowe.” The exhibit noted that

“In the process he produced hundreds of detailed black and white photographs to document almost every aspect of the work that transformed the White House to meet the complexity of the modern presidency while remaining faithful to the spirit of the original James Hoban[11] design . . . His photographs captured not only the work in progress but also the technological challenge of keeping the fragile walls standing while the interior was carved away and rebuilt.”[12]

Abbie Rowe captured nearly every technical aspect of completing the restoration. No detail was too small to be overlooked, from the construction worker rebuilding a wall to the piles of bricks lying on the ground to the salvaging of wood that was to be sent out to Americans who requested a piece of history.

Rowe’s completed photographs of the White House restoration were archived with the Lorenzo Wilson papers. Wilson worked as an architect at the White House for twenty years and was in charge of many projects, including President Roosevelt’s swimming pool and a balcony. Rowe’s photos supplement the architectural blueprints for the White House restoration to present a compelling picture of the restoration’s huge scope and scale.[13]

Bluffs Coffee Shop - Interior,

Interior of the Bluffs Coffee Shop in section 2C on the Blue Ridge Parkway, 1952. Photograph taken by Abbie Rowe. National Park Service photograph.

Bluffs Coffee Shop - Interior,

Customers and the interior of the Bluffs Coffee Shop in section 2C on the Blue Ridge Parkway, 1952. Photograph taken by Abbie Rowe. National Park Service photograph.

Photographing the Blue Ridge Parkway

From its beginning in 1916, the National Park Service enthusiastically publicized the natural wonders found in its parks. Journalist Robert Sterling Yard handled national park publicity in the NPS’s early years. Yard’s efforts included distribution of 275,000 copies of the lushly illustrated National Parks Portfolio and millions of copies of the smaller Glimpses of the National Parks pamphlet.[14] In 1916 alone, historian Barry Mackintosh noted, “the National Park Service also disseminated more than 128,000 park circulars, 83,000 automobile guide maps, and 117,000 [copies of] Glimpses of our National Parks" and "circulated 348,000 feet of motion picture film to schools, churches, and other organizations.”[15]

Stephen Mather and Horace Albright, directors of the National Park Service from 1917 to 1933, led various publicity campaigns throughout the 1920s. Mather and Albright wanted to attract more visitors to prove to Congress that the parks were a worthwhile investment. Arno B. Cammerer, NPS Director from 1933 to 1940, followed in their footsteps. Cammerer gained the support of many journalists and newspapers, including the New York Times, to write in support of the parks. Whereas Mather and Albright’s promotional techniques were aimed at generating political support for the NPS, Cammerer’s methods focused on the economic benefits brought by parks. Cammerer’s main objective, one scholar observed, “was to benefit local economies near the parks, assist the concessioners in the parks, a number of whom were suffering severe financial reversals because of the depression, and indirectly stimulate the national economy.” Franklin D. Roosevelt himself became involved in supporting the National Park Service in the 1930s in order to stimulate the American economy. Roosevelt even declared 1934 a “National Park Year.”[16]

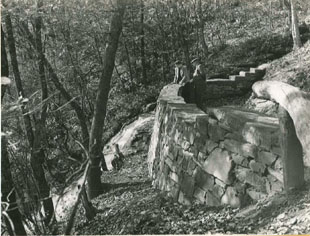

Men looking down from an overlook at the Cascades waterfalls on milepost 271 on the Blue Ridge Parkway. Photograph taken by Abbie Rowe. National Park Service photograph.

During and immediately after World War II, visitors flooded the parks. From 1942 to 1945, seven million members of the military visited the parks with their families. These men and women came because their “pride in the nation's natural and historic heritage had grown during the war.”[17] With this increase in visitors, publicity campaigns of the National Park Service shifted to promoting preservation and conservation.[18] The National Park Service wanted a campaign that would convince Congress to conserve the natural beauty of the parks for future generations. Though the early 1940s saw an increase in visitors, the same time period brought cuts in funds for the National Park Service from $33.5 million in 1940 to $4.7 million in 1945. NPS budgets would continue to languish until the MISSION 66 program brought a long-needed infusion of funds into the parks from 1956 to 1966.[19]

Driveway, landscape, and front side of Moses H. Cone Manor House in section 2G of the Blue Ridge Parkway. Photograph taken by Abbie Rowe. National Park Service photograph.

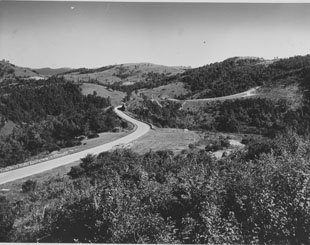

With the end of World War II, interest in the Blue Ridge Parkway surged and staff struggled to fulfill a flood of media requests for publicity photographs. In the spring of 1946, therefore, Parkway staff arranged for Rowe – still employed by the Park Service though assigned to the White House – to spend three weeks taking black and white and color pictures on the Parkway. Dates on Rowe’s 200 Blue Ridge Parkway photographs, however, indicate that this may have been only the first of several trips he made to the Parkway from 1946 to 1952. While certain locations, such as Bluff’s Coffee shop, Bluff’s Lodge, Moses H. Cone Memorial Park, and Linville Falls, stand out as areas of focus for Rowe’s Parkway visits, mileposts noted on his photographs indicate that he traversed much of the road. Rowe’s often stunning Blue Ridge Parkway photographs help today’s generation of Parkway travelers look through a window to the past to see how previous generations of Parkway travelers experienced the “beauty and grandeur” of the Parkway.

Rowe’s Parkway photos range from scenic images highlighting the road’s natural setting to pictures of visitor facilities and Parkway travelers enjoying the road. Reporting on Rowe’s 1946 visit, Parkway Superintendent Sam Weems noted Rowe’s success in capturing visitors out of their cars – a type of image he noted would be needed “if we are to bring home to the motorist traveling the Parkway the fact that their trips will be the more enjoyable for having stopped off for picnic lunches and hiking in the recreation areas enroute [sic].”[20] In 1949, the National Park Service published the “Blue Ridge Parkway, Virginia-North Carolina” brochure, which featured many of Rowe’s photographs.

View Abbie Rowe's Blue Ridge Parkway photographs.

Conclusion

Alligator Back & the Bluffs Parking Area,

View from Alligator Back overlook of the Bluffs parking area from milepost 242.4 on the Blue Ridge Parkway, June 1946. Photograph taken by Abbie Rowe. National Park Service photograph.

Abbie Rowe died of cancer on April 17, 1967, at the age of 61.[21] Although he played a significant role in documenting four presidential administrations, there is little documentation on his own life. Indeed, our search of the following sources and databases yielded no information regarding Rowe: Biography & Genealogy Master Index (BGMI), World Biographical Information System (WBIS) Online, Reference Universe, America: History and Life, Art Index Retrospective: 1929-1984, Documenting the American South, America’s Historical Imprints, American National Biography Online, Academic Search Premier, Project MUSE, SpringerLink, JSTOR, Google Books, Google Scholar, The Internet Archive, Social Network and Archive Context Project (SNAC), The Alexandria Archive Institute, Virginia Historical Society, The Virtual Library of Virginia (VIVA), Arlington Public Library, Handley Regional Library, Readers’ Guide to Periodical Literature, and Encyclopedia – Britannica Online Edition. Historical newspapers were also searched with no results: The Washington Times, The Washington Blade, The Chicago Tribune, The Baltimore Sun, and Washington Post. We contacted Harry Butowsky of the National Park Service, the Harry S. Truman Library, Jackie Holt of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives, the National Archives, and the White House News Photographs Association. Abbie Rowe’s work can be found on the websites of the National Park Service, the National Archives, and the Library of Congress.

Still, Rowe’s photographs let future generations know how he saw the world. He was present for major historic moments in the American national past, as well as for many moments that are only historic to a few, yet he recorded each with equal dignity and respect.

2. Hon. Silvio Conte, “Abbie Rowe, White House Photographer,” Congressional Record Appendix, May 16, 1967.

3. Cornelius W. Heine, “Chapter III,” National Capital Parks: A History (United State Department of the Interior: National Park Service), http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/nace/adhi3.htm (accessed December 6, 2010).

4. Seale, William. The President’s House: A History (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2008), 923.

5. “Historic Photographic Exhibit Debuts at Truman Presidential Museum and Library,” Harry S. Truman Library and Museum, http://www.trumanlibrary.org/news/abbierow.htm (accessed December 6, 2010).

6. “Abbie Rowe Collection.”

7. “Event Photographs,” Harry S. Truman Library and Museum, http://www.trumanlibrary.org/abierowe/events.htm (accessed December 6, 2010).

8. “Historic Photographic Exhibit Debuts at Truman Presidential Museum and Library.”

9. “The President’s Photographer.”

10. “The White House Revealed: Photos of the White House Restoration by Abbie Rowe,” Harry S. Truman Library and Museum, http://www.trumanlibrary.org/abierowe/whitehse.htm (accessed December 6, 2010).

11. James Hoban was the original architect for the White House. His design was chosen in 1792. He also worked to restore the White House to his original plan following its burning in 1814 by the British. For more information on James Hoban please visit: http://www.whitehousehistory.org/whha_exhibits/james_hoban/index.html.

12. “The White House Revealed.”

13. “The White House Collection- Research Sources in the Offices of the Curator,” The White House Collection, http://www.whitehousehistory.org/whha_publications/publications_documents/whitehousehistory_09.pdf (accessed December 6, 2010).

14. Anne Mitchell Whisnant, Super-Scenic Motorway: A Blue Ridge Parkway History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 23.

15. Barry Mackintosh, Interpretation in the National Park Service: A Historical Perspective, (Washington, D.C.: History Division, National Park Service, Department of the Interior, 1986), 4-5.

16. Donald C. Swain, “The National Park Service and the New Deal, 1933-1940,” Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 41, No. 3 (Aug., 1972), 317-318.

17. Janet A. McDonnell, “World War II: Defending Park Values and Resources,” The Public Historian, Vol. 29, No. 4 (Fall, 2007), 32.

18. McDonnell, “World War II,” 17.

19. Whisnant, Super-Scenic Motorway: A Blue Ridge Parkway History, 267.

20. Sam Weems, “1946 Superintendent Report to Director,” received from Blue Ridge Parkway, National Park Service Archives.

21. “Abbie Rowe Dies at 61; Lensman of Presidents,” The Washington Post, April 19, 1967, Section B.