Grandfather Mountain and the Parkway's "Missing Link"

By Anne Mitchell Whisnant

One of the most cherished and widely retold stories in recent North Carolina history is the tale of the Blue Ridge Parkway’s “missing link” at Grandfather Mountain. This approximately seven-mile section of the road remained uncompleted for two decades after the rest of the Parkway was finished in the late 1960s. It finally opened in 1987, fifty-two years after Parkway construction began in the midst of the Great Depression.

At the heart of the popular story is the tale of the how Grandfather Mountain owner Hugh Morton “saved” what is usually described as an ecologically fragile yet pristine and undeveloped mountain from the National Park Service’s supposed plans to route the Blue Ridge Parkway “over the top” of the beloved peak in the 1950s and 1960s. Countless publications have portrayed Morton as a lifelong conservationist who single-handedly halted what is characterized as an environmentally irresponsible Park Service plan to take – in Morton’s oft-repeated phrase – a “switchblade to the Mona Lisa.”

In the end, Morton forced the Park Service to adopt a lower route. The construction of the iconic Linn Cove Viaduct – an engineering marvel that greatly reduced construction damage along a quarter-mile part of the route that traversed an unstable boulder field – provides a neat end to this simple, but misleading account.

The historical record of the battle between Morton, North Carolina’s State Highway Commission (responsible for Parkway land acquisition in the state), and the National Park Service (NPS) over the Parkway route reveals a much more complicated drama. But with the conflict dragging out for more than thirty years and involving multiple shifting route and land acquisition proposals and a changing cast of landowners and public officials, it is no wonder casual observers who have had little access to original historical documents are vague about the episode’s specifics.

As it has been retold without reference to those documents, key parts of this story – including the fact that the Linn Cove Viaduct had virtually nothing to do with resolving the route conflict – have dropped out of view over the years. But these forgotten elements re-emerge vividly from archival collections of historic planning maps for the Parkway, and from Hugh Morton’s own photographic record. These maps and images now digitized and available together for the first time on this site, and in the related Hugh Morton Collection of Photographs and Films, help untangle the story.

Here we present a set of maps that tell the tale on the ground. Over at A View to Hugh, a related essay, "Roads Taken and Not Taken: Images and the Story of the Blue Ridge Parkway's 'Missing Link'" examines the episode through Morton's camera lens.

The story begins in the 1930s, when the state of North Carolina paid Morton’s grandfather Hugh MacRae’s Linville Company for a right-of-way for the Parkway along what is now Highway 221 (known historically as the Yonahlossee Road).

By the 1940s, however, the Park Service and state engineers had concluded that the twisting and torturous Highway 221 could not be adapted to Parkway standards. With some cooperation from the MacRae family, they launched an ultimately unsuccessful effort – spearheaded by longtime parks advocate and MacRae family friend Harlan Page Kelsey – to purchase all of Grandfather for the Parkway. That effort ran aground in the late 1940s when Morton returned from service in World War II, took the helm of the company, and declared the mountain no longer for sale.

Park Service and North Carolina highway officials then plotted another route for the Parkway (known during the controversy as the “high route”) that lay about 600 feet up the mountain from 221 and included a 1700-foot tunnel through Pilot Ridge.

Meanwhile, bent on harvesting what he termed “rich crops of tourists,” Morton in 1952 blasted a road to one of the mountain’s summits, where he launched a wave of development that began with the “Mile-High Swinging Bridge,” a new parking area and a small gift shop later that year. To recover his costs, he hiked the price of admission to Grandfather’s peak from $.50 for car and driver ($.25 for additional passengers) to $.90 apiece for adults. In 1961, Morton built a much larger “Top Shop” to replace the modest early structure he had initially built at the summit parking area.

In the midst of this bustle of activity, the state acquired the new “high route” right-of-way by eminent domain in 1955. Morton protested loudly to Governor Luther Hodges (for whose 1956 gubernatorial campaign he managed publicity), and the Highway Commission was forced to deed the land back to him in 1957.

For the next thirteen years, stalemate reigned, as Morton – supported by governors (and personal friends) Hodges, Terry Sanford, and Dan K. Moore – stood firmly against the “high route.” The Park Service, for its part, threatened simply to leave the Parkway unfinished rather than move the road lower on Grandfather.

Ultimately, mobilizing his close connections with those in power in state government, Morton triumphed. Facing staunch state refusal to acquire land for the “high route,” the Park Service agreed to what Morton termed a “compromise” route between the “high route” and 221. Construction began along this line in 1968.

Examining the set of georeferenced historic Parkway maps (maps that have been aligned with a their geographic location and overlaid upon a Google Earth satellite image or current map) makes it easy to see the evolution of the conflict, and, especially, the relationship of the three route proposals (“high route,” “middle route” and 221/Yonahlossee Road route) to one another, and to Morton’s tourist development on one of Grandfather’s peaks. The maps below are particularly instructive. You may view them individually here, or you may download all of them to Google Earth, where it is possible to layer them all upon each other, adjust the transparency of each, and turn them on or off as desired.

- Proposed Grandfather Mountain

- This map (based upon 1940 data) was probably drawn in the late 1940s (the date estimate is partly based on the fact that the "toll road" shown ascending Grandfather does not, in this map, yet reach the location of the present Mile-High Swinging Bridge, which was built in 1952). This map clearly depicts the proposed "high route” for the Parkway at Grandfather Mountain, which included the planned tunnel through Pilot Ridge. The "high line” proposal was laid out by the National Park Service and officials at the North Carolina State Highway Commission in the 1940s after it became clear that using existing 221 (former Yonahlossee Road) for the Parkway would not be feasible. Overlaid upon a modern map of the same area (click the link for "interactive map"), this map makes it easy to see the relationship between U.S. 221, the proposed "high" route that Hugh Morton opposed, the Mile-High Swinging Bridge, and the eventual line between 221 and the "high" route along which the Parkway was finally built.

- Grandfather Mtn. Area-Acquisition Map

- This map, signed in 1944, clearly indicates the complicated land situation in the Grandfather Mountain vicinity in the mid-1940s, as negotiations for a Blue Ridge Parkway route clear of U.S. 221, where the North Carolina State Highway Commission had acquired an initial right-of-way from the Linville Improvement Company in the late 1930s. The map shows the proposed "high" Parkway route with its projected Pilot Ridge tunnel and an optional loop around Pilot Knob.

- Grandfather Mt. Acquisition--Kelsey Proposal

- This 1946 map indicates the status of various lands in the vicinity of Grandfather Mountain, NC, in the mid-1940s, when Morton family associate Harlan P. Kelsey was trying to raise funds to purchase 5,555 acres (including all of Grandfather Mountain) for incorporation into the Blue Ridge Parkway. Kelsey also advocated NPS purchase and protection of a much larger acreage along the Parkway throughout the region (the area outlined in yellow). The area in purple had already, in the late 1930s, been purchased by the State of North Carolina for the Parkway in this region.

- Public Road System Plan

- This map, updated as of 1951, shows the "high route" proposal for the Parkway around Grandfather Mountain in relation to the existing road networks in that region on the eve of the long conflict between Hugh Morton and the National Park Service over the Parkway route.

- Grandfather Mt. Lands Map

- This 1962 map clearly shows, in purple, the final "middle route" later acquired for the Parkway around Grandfather Mountain. The eventually rejected "high route" is also shown, while hash marks indicate Forest Service land as well as the land along U.S. 221 originally acquired in the late 1930s by the North Carolina State Highway Commission for the Parkway.

- Parkway Location

- This 1962 map includes a number of taped-on annotations indicating local uses (including ingress and egress from various properties) of U.S. 221 through the Grandfather Mountain area. These annotations delineate part of the reasoning advanced by the State of North Carolina and the Park Service for not upgrading and adapting 221 for Parkway use, as had been originally proposed in the 1930s. This map also shows lands appropriated in 1955 for the proposed Parkway "high route" with Pilot Ridge tunnel, as well as, in dotted green, what appears to be an emergent identification of what would become the "middle" (final) route. Topographic markings indicate relative elevations of each of the three possible routes. Finally, a comparison of this map to the current landscape (to see overlay, click "interactive map" link) clearly shows that the present Parkway location through the area where the Linn Cove Viaduct now stands would have been the same whether the "high" or "middle" route had been selected; the two options diverged after the north end of the Viaduct. Construction of the Viaduct, it is clear, had little to do with the resolution of the contentious issue of where to route the Parkway at Grandfather.

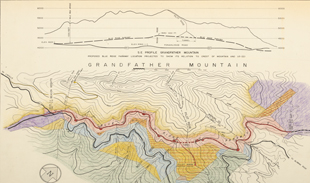

- Parkway Location Grandfather Mt.

- This map, probably developed in the late 1950s or early 1960s, includes a profile view of Grandfather Mountain indicating the relative elevations of the "high route" that Grandfather owner Hugh Morton opposed and the originally proposed Parkway route along U.S. 221 (formerly known as the Yonahlossee Road). The profile view, which was published in several regional newspaper accounts of the conflict in 1962, attempts to demonstrate that even the "high route” did not ascend near either Morton's Mile-High Swinging Bridge or other peaks of Grandfather Mountain. This map predates the proposal for the "middle" (eventually constructed) route, but does clearly indicate the placement of the proposed Pilot Ridge tunnel, which was ultimately abandoned.

- Overlay Showing Lands Appropriated by NC - SHC for Middle Line - Jan. 1965

- This 1965 overlay upon a 1962 map clearly marks, in green, the "middle line" lands finally agreed upon between the National Park Service, the State of North Carolina, and Hugh Morton for the Parkway route around Grandfather Mountain. The earlier proposed "high route" land boundary is also clearly visible, as are the land ownership boundaries indicating land owned by Hugh Morton ("Linville Improvement Co."), the U.S. Forest Service, and various other private landowners.

See also:

- Land Acquisition Maps Section 2-H

- These maps are the State of North Carolina's maps showing the boundaries of the land acquired for the Parkway route near Grandfather Mountain.

- Parkway Land Use Map Section 2-H

- These maps are the as-built representations of the Parkway near Grandfather Mountain.