Highways and Byways of the Past

Women’s Groups and Memorial Forests Along the Blue Ridge Parkway

By Shannon Harvey

If the highways and byways of the past attract you, search out its history and its records, and preserve its guideposts for others to note.

- Florence Hague Becker, President-General, National Society Daughters of the American Revolution, 1936

In 2000, retired U.S. Service Forest Ranger Jim Holbrook encountered a surprising reference in a tourist guidebook. The guidebook said that a forest dedicated to the North Carolina veterans of the Confederacy stood somewhere along the Blue Ridge Parkway. Holbrook had never heard of the forest, despite 33 years of work for the Forest Service and membership in the Sons of Confederate Veterans. The marker for the memorial forest had long since disappeared, and Holbrook quickly went about acquiring a new one. Explaining his connection to the forgotten forest, Holbrook remarked: “I have two great-grandfathers who served in the Confederate army . . . I knew that two of those 125,000 trees were planted for them.”[1] For Holbrook, the name and symbolic number of trees were sufficient for him to connect his ancestors, and consequently himself, to the forest. But what was its significance to the people who planted it?

Holbrook had stumbled upon the North Carolina Confederate Memorial Forest, established by the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) in the early 1940s. The forest is one of several thousand Confederate memorials and monuments in the southern United States erected during the early twentieth century. Viewed in this context, the memorial forest was a rather typical undertaking for its time – a moment when robust and active white women’s groups tasked themselves with what historian Fitzhugh Brundage has described as a “coordinated fashioning of a public past.”[2] As the living memory of the Civil War died along with veterans and non-combatants, this younger generation of women created a set of social and cultural memorial practices that invented and sustained a Lost Cause interpretation of the Civil War, often framed by a longer history of EuroAmerican settlement in the Americas. [3] The markers they installed are still omnipresent at civic centers, university campuses, and other public spaces in the South.

Yet Confederate memorials rarely took the form of forests. This forest takes us back to a moment when conservative social groups actively supported environmental projects, understanding that the nation’s historic, cultural, and natural resources were inextricably connected. Furthermore, the forest’s location alongside the Blue Ridge Parkway suggests the symbolic richness of the parkway project in the imaginations of North Carolinians in the 1930s and 1940s. Planted alongside the proposed route of the parkway, the forest juxtaposed a version of North Carolina’s past with a vision for its future. Visitors to the parkway would have viewed these juxtapositions of past and the present, man-made and natural, in light of the power relationships between men and women, elites and non-elites, and whites and blacks that defined pre-World War II North Carolina.

Narrating North Carolina’s Landscapes

The Blue Ridge Parkway has often been described as a “silver ribbon” woven through a pristine landscape. Historian Anne Mitchell Whisnant has demonstrated, however, that extensive economic, political, and social labor—not to mention physical engineering— went into producing the parkway.[4] The appearance of “pristine” wilderness and a road that only lightly touches the landscape are themselves careful constructions that shape visitors’ experience of the parkway.

Similarly, the memorial forest is a constructed space that required not only fundraising, planting, and coordination between agencies and citizen groups, but also social and cultural labor. The women who initiated the project saw the memorial forest as part of a network of historic and natural resources within the state of North Carolina, one that could do similar civic work as more traditional, and often figurative, memorial forms.

The national publications produced by the UDC and the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) in the 1930s and 40s make clear that they believed that notable landscapes were worthy objects of preservation efforts in their own right. A site could be valuable because an event of historic significance that had occurred there, or its value could be intrinsic— emanating from its unique natural features or particular beauty. Either quality could be used to instill civic pride and educate citizens. Edifying narratives and illustrations of the landscape helped viewers understand the importance of what they were seeing — either in person or on the page — and were common in the literature of these organizations. These publications privileged certain historical narratives and ignored others, rendering a landscape that complemented the political and social aspirations of the white women who made up the groups’ ranks.

Nestled alongside the proposed parkway, the memorial forest also borrowed from the foundational narratives of the parkway itself. Despite the fact that scenic landscapes were badges of national and local pride, conservation efforts at these sites often competed with economic interests. The construction of the Blue Ridge Parkway promised to resolve that tension by holding out the possibility that conservation and economic opportunity could go hand in hand. As one article in a UDC publication explained, “with two millions tourists, annually . . . this mountain region will have many hundreds of times the value to the people of the Southern Appalachians, than the mere intrinsic worth of the virgin timber on the slopes of their giant ridges.”[5] Moreover, these tourists represented a large new audience for North Carolina’s historic and natural heritage.

This cover of an issue of Southern Magazine from 1937 devoted to North Carolina juxtaposed a mountain valley landscape with a border illustration that evokes a romanticized antebellum South. A couple walks under a willow tree, while a “pickaninny,”a racial caricature of an African American child, is surrounded by cotton bolls.[11]

Southern Magazine, April 1935

The August 1935 issue of UDC’s Southern Magazine introduced UDC members across the nation to North Carolina.[6] The issue highlighted a range of attractions, including Confederate monuments, picturesque scenery, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, as well as the proposed Appalachian “scenic highway.”[7] Tellingly, Southern Magazine’s North Carolina tour began with a frontispiece depicting the imagined baptism of the first English child born in the American colonies, Virginia Dare.[8] The unexplained disappearance of the colony at Roanoke had long provoked speculation about the fate of the community. Southern Magazine relayed one particularly popular myth in which Dare is transformed into a white doe.[9] This casting of Dare as the white doe figuratively naturalized the English colonial population at the same time that it feminized the landscape. In this capacity, Virginia Dare and the white doe served as mythological cornerstones on which European settlement and dominion over the landscape were legitimized. By wedding English colonialism with the North Carolina landscape, this origin story elided other actors, consigned Native Americans to pre-history, and emphasized European settlement as the meaningful starting point of North Carolina history.

Similarly, the Southern Magazine article “Racial Elements In North Carolina’s Population” replicated a narrative in which North Carolina transitioned from a land inhabited by Native Americans to one dominated by EuroAmericans. Touching only briefly on Native American influence, the author concluded “we find today that North Carolina is the product of the co-operative efforts, struggles, and sacrifices of the English, Scotch, and German.”[10] The contributions of African Americans were omitted altogether. In fact, publications such as Southern Magazine rarely mentioned African Americans beyond employing them to evoke a romanticized image of the antebellum South. These images of the Old South suggested that race and gender relations were hierarchical, stable, and uncontested during this period. When paired with contemporary images of state landscapes, they implied continuity over time.

Southern Magazine’s 1937 cover, for instance, featured a photograph of a mountain valley landscape framed by a border print in which white antebellum figures walked under willow trees while a “pickaninny” figure surrounded by cotton bolls floated above their heads. Notably, in this border print white elites moved through the outdoor space while pursuing some kind of leisure activity. By contrast, the African American child’s relationship to the land, signified by the cotton bolls, was a working relationship. The magazine encouraged its readers to adopt the perspective of the white couple strolling under the moonlight — privileged visitors taking in the scenery, not laborers working the land.

Women’s Groups and Conservation in the 1930s and 40s

Historically inflected and often romantic views of the landscape were powerfully conjoined with scientific rationales for environmental protection in the 1930s and 40s. While timbering operations devastated western North Carolina forests, agricultural communities across the country struggled with drought, disease, and failed crops. Human action had intensified the impact of these calamities, leading to wide-scale soil degradation and erosion. Citizen groups worked to restore damaged and deforested areas and protect “pristine” areas, citing concerns about soil erosion, air, and water quality alongside aesthetic and historic motivations.[12]

The national leadership of the DAR adopted this more scientific rationale for conservation. They educated members about environmental problems such as soil erosion, encouraging action to combat these problems. Daughters of the American Revolution magazine featured articles written by scientists on environmental topics, and many state divisions had conservation committees that helped organize and record environmental advocacy efforts.[13] For instance, one chapter reported at the state convention that they had started a nursery for native trees and shrubs, while another had focused on feeding bird populations over the winter.[14]

This environmentalist perspective is evident in a letter writing campaign initiated by women’s groups in Lenoir, North Carolina, in the 1930s to urge Senator Robert Lee Doughton to protect Grandfather Mountain from continued deforestation.[15] While the Wise and Other-wise Club argued for preservation of the mountain on the basis of its “beauty and grandeur,” the Lenoir DAR chapter wrote about the “serious effect [deforestation on Grandfather] will have on our water supply and our climate.”[16]

Combining historical and environmental preservation initiatives, the DAR encouraged tree planting as a form of memorialization. DAR leaders urged chapters to plant trees in honor of the sesquicentennial anniversary of the writing of the Constitution, explaining that, “chapters could do no greater public service than inaugurate such projects,” and went on to describe one such project by a group of Virginia school children as “citizenship making of the finest pattern.”[18]

In anticipation of the fiftieth anniversary of the DAR’s founding, national leadership proposed that each state division plant and dedicate a “jubilee forest” of at least one acre of trees in honor of the anniversary. Most states far exceeded this minimal goal, in part by capitalizing on the United States Forest Service’s Penny Pines Project, which encouraged people to donate a penny to sponsor the planting of a pine seedling. These trees were usually planted in existing forests and parks, though at times land was reforested and then donated to government park agencies. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) planted the seedlings. Through the DAR jubilee forest project alone, approximately 2,400 acres and 2,500,000 trees nationwide were planned for planting.[19]

North Carolina’s Memorial Forests

A natural location for North Carolina’s DAR Jubilee Forest was alongside the proposed parkway. Though the state division entertained the possibility of expanding an existing DAR park site on Rendezvous Mountain near Wilkesboro, the over four mile distance between the site and parkway may have made this proposal untenable. [20] Instead, the North Carolina DAR chose a site in Pisgah National Forest near mile marker 422. Close to the Devil’s Courthouse and just a few miles from Graveyard Fields, this particular stretch of forest had been cut and burned in 1925.[21] Fifty thousand trees were planted at a cost of $500, and the North Carolina Golden Jubilee Memorial Forest was dedicated in May of 1940.[22]

This image of Devil’s Courthouse was taken in 1955 by Hugh Morton just after the section of the parkway that ran alongside the DAR Jubilee Forest was completed.[23]

North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives

State regent Ethel Harris Fisher first proposed the UDC memorial forest in 1939.[24] The memorial forest, she hoped, would keep “forever green the memory of North Carolinas [sic] 125,000 Confederate Soldiers.”[25] Not coincidentally, Fisher also served as state historian of the DAR during the planning stages for the Jubilee Memorial Forest.[26] While there is at least one other UDC memorial forest (in Tennessee), the North Carolina division of the UDC did not have the same national support for a reforestation project of this size as the North Carolina division of the DAR. National UDC literature and conference minutes never mentioned the forest, so it seems likely that Fisher imported the idea from the DAR. Though UDC Memorial Forest Committee member Eva Barber recalled having “climbed the hills, tramped the thorns that tore our hose as we [Fisher and Barber] tried to find the most beautiful spot on which to establish this memorial,” the UDC forest was ultimately planted just a few hundred feet from the Jubilee Forest.[27]

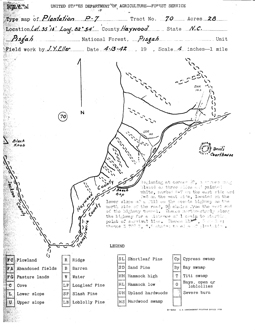

Map of Plantation P-7, 1942. The location of the DAR and UDC forests are roughly sketched on the north side of the proposed parkway. Devil’s Courthouse is to the south and is situated between the two forests. [28]

Blue Ridge Parkway Archives

Asheville native Ethel Fisher had a longstanding interest in the landscape of western North Carolina and the Blue Ridge Parkway project. In 1936 she wrote an article for Daughters of the American Revolution magazine that sang the praises of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. She located the Great Smoky Mountains both within and outside of history, explaining that “although four centuries have elapsed since De Soto, the great Spanish explorer, passed through and left the footprints of a white man, the Great Smoky Mountains area of North Carolina has remained deep fastnesses of primeval forests, mysterious in their beauty and majestic grandeur.”[29]

While this characterization of the region as untouched and static is a creative fiction (several communities were relocated when the park was formed), this image of unspoiled, natural grandeur set the stage for Fisher’s sales pitch for the Blue Ridge Parkway.[30] “Of greatest interest to the reader,” she asserted, “will be the information that the Great National Scenic Highway, recently granted by the government, traverses this wonder section like a silver ribbon winding in and out the unrivaled mountains.”[31] The promise of the parkway, Fisher suggested, was access to unparalleled treasures not seen since de Soto’s sixteenth-century trek. Though the newly planted UDC forest could not compete with the “majestic grandeur” of the Great Smoky Mountains, by laying claim to real estate along the “silver ribbon,” Fisher wove together De Soto, the Great Smoky Mountains, and other regional landmarks — the Black Mountains, Rhododendron Gardens, and Biltmore estate — with the history of the UDC and the Confederate men they memorialized.

Take a tour of Fisher’s guide to the proposed parkway, including contemporary images and postcards of the sites Fisher mentions in her article on the Great Smoky Mountains.

Remembering and Forgetting the Southern Past

The North Carolina Confederate Memorial Forest, by chance and by design, attracted more attention and praise than the DAR Jubilee Forest. The UDC was a more influential organization regionally, and their forest was larger and more symbolically significant. They planted 125,000 trees on 125 acres, one tree for each North Carolinian who served in the Confederate army. North Carolina, the UDC state division constantly reminded audiences, had provided the largest volunteer military force of any southern state in the Confederacy. Additionally, the forest had three separate dedication services in 1942, 1956, and 2001. Each service brought renewed public attention to the memorial.

The Confederate Memorial Forest was first dedicated in 1942 for a crowd of 150 at the Vanderbilt Hotel in Asheville.[32] Josephus Daniels delivered the keynote address. Daniels was the longtime editor of the Raleigh News and Observer, had served as Secretary of Navy under Woodrow Wilson, and was most recently the United States ambassador to Mexico. He had previously spoken at the dedication of other UDC monuments, and his wife, Adelaide Daniels, was active in both the DAR and UDC.[33] Daniels was also a major advocate of the Blue Ridge Parkway, and his influence in Washington, D.C., was instrumental in having the parkway routed through North Carolina in 1934.[34]

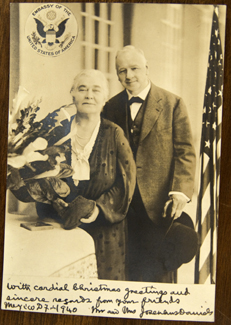

Josephus and Adelaide Daniels during his tenure as ambassador to Mexico, 1940. The ways in which both Daniels performed public work—Josephus through his government positions and at the News and Observer and Adelaide through women’s groups—shows how the gendered, parallel worlds that elite men and women occupied at this time overlapped and worked in tandem on related issues. [35]

Southern Historical Collection

In his dedicatory speech, Daniels compared the plight of European nations under fascist rule to that of southern states under Reconstruction. Noting the high number of southern men who voluntarily enlisted during the current conflict, Daniels argued they did so because they empathized with the European people. “It is because Southern people, aided by noble patriots in the North, overcame military rule and regained control of their affairs,” Daniels argued, “that they have no doubt the suffering European nations will throw off rule by force and once again order their own way of life.”[36] Though Daniels qualified his words by noting that the “mistreatment” of southerners was “nothing compared to the treatment now being given to Nazi-conquered people,” his comparison was not a matter of disinterested historical observation. After the election of a bi-racial state government of Republicans and Populists in the 1890s, Daniels had used his position as editor of the News and Observer to disseminate the white supremacist platform of the Democratic Party. Its viciously racist attack campaign featured a series of political cartoons drawn by Norman Jennett that variously depicted black men as buffoons, vampires, other demons, devils, and lechers.[37]

In 1898, Daniels had argued that white North Carolinians were suffering not under northern rule, but under “Negro Rule” and “Negro Domination.” The Democratic Party’s campaign ultimately led to a riot by white citizens and coup d’etat in Wilmington in which an unknown number of African American citizens were murdered, and several thousand more fled the city entirely. Prominent white and black Republicans and business leaders were banished, and white Democrats forcibly ousted the elected city government.[38] These events precipitated the disfranchisement of African Americans in North Carolina and ushered in the era Jim Crow legislation and social practice.

Echoing Daniels, UDC state regent Katherine Everett asked the audience at the forest site to consider how American soldiers in Europe and Confederate soldiers both fought for the ideal of liberty.[39] It was this version of the public past—that whites in the South had been the oppressed, not the oppressors—that Daniels and Everett chose to narrate on this occasion.

Wartime shortages prevented the UDC from marking the forest with a bronze plaque during the 1942 dedication. In 1956, a bronze plaque marker mounted on a white boulder was unveiled at the site. The fourteen-year gap allowed the saplings time to grow, though as Forest Supervisor Donald J. Morris explained, the spruce trees were still forcing their way through the “scrubby hardwoods” that had sprouted after the 1925 fire.[41] More significantly, in 1955 the stretch of the Blue Ridge Parkway that the UDC and DAR memorial forests fronted had officially opened, meaning that for the first time these memorials were readily accessible to the public.[42] The 1956 ceremony featured representatives from several women’s organizations in addition to the UDC, including the DAR, the Daughters of 1812, and the Daughters of the American Colonists. Governor Luther Hodges was invited.[43] Blue Ridge Parkway superintendent Sam Weems accepted the marker on behalf of the National Park Service.[44]

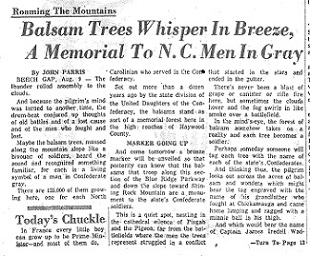

Upon the occasion, Asheville Citizen-Times columnist John Parris extolled the evergreen memorial. In his animated description, the forest transformed into an army standing at attention. “There’s never been a blast of grape or canister or rifle fire here,” Parris wrote, “but sometimes the clouds hover and the fog swirls in like smoke over a battlefield. In the mind’s-eye, the forest of balsam somehow take on a reality and each tree becomes a soldier . . . they come alive especially . . . when the thunder rolls assembly to the clouds.”[45] As in the story of Virginia Dare and the white doe, Parris entangled and populated the landscape with the memory of a select group of historical actors.

John Parris, “Balsam Trees Whisper in Breeze, A Memorial to N.C. Men in Gray,” Asheville Citizen-Times, 10 August 1956.[46]

Conclusion

White women engaged in historical preservation and environmental conservation projects exploited the strengths and negotiated the weaknesses of their social position. They stamped the landscape with a version of North Carolina history that validated the experiences and perspectives of whites, particularly elites who could claim status through lineage to noteworthy persons. Nonetheless, their service was an unpaid corollary to the official work that their husbands engaged in, and the public past that they celebrated was dominated by the accomplishments of their male forebears.

Despite Parris and Fisher’s faith that a living, evergreen memorial would stand the test of time, in the summer of 1978 the bronze plaque marking the Confederate Memorial Forest was stolen.[47] Although the UDC requested a new marker, the National Park Service declined to replace it fearing it would be vandalized again, and suggested a standard NPS wooden sign instead.[48] That they anticipated this outcome hints at the changing status of Confederate memory in the South. Between the initial proposal for the memorial in 1939 and the theft of the marker in the late 1970s, the political associations and public reception of Confederate symbols had changed dramatically. The Confederate battle flag, for instance, became strongly associated with segregationist politics with the emergence of the Dixiecrat movement in 1948. By the 1950s and 60s, the battle flag was widely used to protest against the expansion of African American civil rights and became the banner of organized white supremacist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan.[49] Civil rights activists, in turn, began challenging the flag’s presence in government buildings and other public spaces in the 1970s. Although the flag has always drawn more fire than other Confederate symbols, Confederate memorials and monuments were also increasingly subject to public scrutiny and criticism.

Absent the bronze marker, by the late twentieth-century most people had forgotten the original intention behind this particular stand of trees. Despite Jim Holbrook’s successful rededication efforts, the 2001 records of the dwindling and aging UDC did not even mention the rededication service. The newly dedicated Confederate Veterans Memorial Forest (as it was mislabeled in its 2001 reincarnation) has trees that now stand over fifty feet tall. The forest is something of a paradox; its success has made it recede from view. Drivers cruising by would have a hard time distinguishing the mature stand of trees from the forest around it.

Should a driver pull over near mile marker 422 to stretch her legs and spot the new marker, it is unclear that she would take away the founders’ intended lessons. The Lost Cause is now a minority interpretation of the Civil War, its origins, and its aftermath. This fact stands in awkward contrast to the outsized mark that that interpretation’s supporters made on the southern landscape during the early twentieth century. Seeking out and preserving the guideposts along the highway of the past, DAR President-General Florence Becker would no doubt agree, takes a sustained investment of labor and commitment.[50] Confederate memorials, shorn of the once widespread rituals of the Lost Cause—the citizen organizations, essay competitions, parades, ceremonies, and innumerable other small and large ways that memory was sustained and performed—stand somewhat naked before modern eyes.

Yet the effects of decades of intentional and systemic social, political, and economic marginalization of non-whites that the Lost Cause interpretation of the Civil War justified persist. The South’s forest of Confederate markers is so ubiquitous as to be unremarkable to some—mere background noise— while many other southerners see too well both the forest and the trees and are reminded of the people whose stories they do not honor or tell.

Notes

2. W. Fitzhugh Brundage, The Southern Past: A Clash of Race and Memory (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005), 14.

3. For more information see: W. Fitzhugh Brundage, The Southern Past: a Clash of Race and Memory (Cambridge, MS: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005), and Karen Cox, Dixie’s Daughters : the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2003). For information on memorials in the state of North Carolina specifically, see: W. Fitzhugh Brundage, et al., Commemorative Landscapes of North Carolina, 19 March 2010, http://docsouth.unc.edu/commland>/a>.

4. Anne Mitchell Whisnant, Super-scenic Motorway: A Blue Ridge Parkway History (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2006).

5. “Appalachian Parkway—North Carolina,” Southern Magazine, August 1935, 10.

6. Southern Magazine regularly featured former Confederate states and states that had UDC chapters. These state features served as a way for chapters to showcase their home states to the larger national organization.

7. “Frontispiece—Baptism of Virginia Dare, Roanoke Island,” Southern Magazine, August 1935, 4. This issue was devoted to the state of North Carolina.

8. Yet another North Carolina issue of Southern Magazine from October-November 1937 was entirely devoted to the 350th anniversary of Virginia Dare’s birth and celebrations across the state.

9. R. B. Creacy, “The Legend of the White Doe,” Southern Magazine, August 1935, 23, 54.

10. A. R. Newsome, “Racial Elements In North Carolina’s Population,” Southern Magazine, August 1935, 47.

11. Southern Magazine, April 1935, cover illustration.

12. Mrs. J. L. Nelson to Robert Lee Doughton, 31 August 1933, Folder 245, in the Robert Lee Doughton Papers #2862, Southern Historical Collection, Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Mrs. A. G Jonas to Robert Lee Doughton, 2 October 1933, Folder 245, in the Robert Lee Doughton Papers #2862.

13. “Conservation and Thrift,” Report of the Thirty-seventh Annual State Conference of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution of North Carolina, 30-31 March - 1 April 1937 (Charlotte, NC), 108-109; see also: Hugh H. Bennet, “History Is Being Made on Our Land,” Daughters of the American Revolution magazine, March 1952, 261-264, 273.

14. “Conservation and Thrift,” Report of the Thirty-sixth Annual State Conference of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution of North Carolina, 3-5 March 1937 (Asheville, NC), 107.

15. For more on preservation efforts on Grandfather Mountain and its eventual connection to the Blue Ridge Parkway, see Anne Mitchell Whisnant, Super-scenic Motorway: A Blue Ridge Parkway History (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), chapter 7.

16. Nelson to Doughton, 31 August 1933; Jonas to Doughton, 2 October 1933.

17. “Grandfather Mountain Lumbering Operations,” February 1934, Courtesy Blue Ridge Parkway Archives, http://docsouth.unc.edu/blueridgeparkway/content/1028/

18. “Conservation,” Daughters of the American Revolution magazine, September 1936, 977-978.

19. “Jersey D.A.R. Finishes Penny Pines Planting: Memorial Forest to Be Given to State at Ceremony Tuesday,” New York Times, 13 October 1940, 60.

20. At least four miles as the crow flies; Lucy F. Finley, “Rendezvous Mountain D.A.R. Park,” Report of the Thirty-sixth Annual State Conference of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution of North Carolina, 3-5 March 1936 (Asheville, NC), 126.

21. D. J. Morris to Mrs. R. N. Barber, 13 August 1956, Box 34, Record Group 5, Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.

22. “D.A.R. Dedicates 50,000 Trees in Memorial Forest,” Asheville Citizen-Times, 16 May 1940, 3; Nancy S. O’Brien, “Conservation,” Year Book and Report of the Forty-first Annual State Conference of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution of North Carolina, 4-6 March 1941, Wilson, NC, 88-89. For a full list of DAR forests, see the DAR website: http://www.dar.org/natsociety/content.cfm?id=262&fo=y&hd=n

23. Hugh Morton, Devil’s Courthouse from New Section of Blue Ridge Parkway Between Wagon Road Gap and Soco Gap, NC, Photograph, 1955, Hugh Morton Photographs and Films (P081), North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives.

24. “Report of the Executive Board,” Minutes of the Forty-third Annual Convention of the United Daughters of the Confederacy North Carolina Division (Raleigh, NC: Edwards & Broughton Printing Company, 1939), 71-73. Fisher served as state regent in 1939 and 1940.

25. Eva Bell Barber, “Report of Memorial Forest Committee,” Minutes of the Sixtieth Annual Convention of the United Daughters of the Confederacy North Carolina Division (Wilmington, NC: Wilmington Printing Company, 1957), 66.

26. “Officers 1936-1937,” Report of the Thirty-sixth Annual State Conference of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution of North Carolina, 3-5 March 1936 (Asheville, NC).

27. Eva Bell Barber, “Report of Memorial Forest,” Minutes of the Forty-sixth Annual Convention of the United Daughters of the Confederacy North Carolina Division (Raleigh, NC: Edwards & Broughton Printing Company, 1942), 96.

28. J. Y. Eller, “Map of Plantation P-7,” 13 April 1942, Box 34, Record Group 5, Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.

29. Ethel Harris Fisher, “The Great Smoky Mountains,” Daughters of the American Revolution magazine, September 1936, 925.

30. Whisnant, Super-Scenic Motorway, 132.

31. Fisher, “Great Smoky Mountains,” 925.

32. Barber, “Report of Memorial Forest,” (1942), 96-97.

33. “Confederate Monument, Roxboro,” Commemorative Landscapes of North Carolina, http://docsouth.unc.edu/commland/monument/84/, accessed 12 December 2012.

34. Whisnant, Super-Scenic Motorway, 88-89.

35. “Mr. and Mrs. Josephus Daniels,” 1940, Folder 165, in the Josephus Daniels Papers #203, Southern Historical Collection, Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

36. “Forest is Dedicated to N.C. Men of Confederacy,” Asheville Citizen-Times, 13 July 1942, 1, 3.

37. For examples, see this collection of Norman Jennett’s cartoons at The North Carolina Election of 1898: http://www.lib.unc.edu/ncc/1898/sources/cartoon.html

38. 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Commission, 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Report (North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 31 May 2006), 1-2, http://www.history.ncdcr.gov/1898-wrrc/report/report.htm, accessed on 12 December 2012.

39. “Forest is Dedicated,” 3.

40. “Forest is Dedicated,” 3.

41. D. J. Morriss to Mrs. R. N. Barber, 13 August 1956, Box 34, Record Group 5, Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.

42. “An Evergreen Memorial,” Asheville Citizen-Times, 25 October 1955.

43. Hodges did not attend the August 11, 1956, dedication, but on August 18, 1956, he attended a tree planting in Roanoke County and made an appearance at The Lost Colony, playwright Paul Green’s dramatic interpretation of the story of the first English colony in the Americas. The Lost Colony has been performed every year near Manteo, NC, since 1937.

44. “Program for Unveiling of Memorial Marker Honoring 125,000 N.C. Confederate Veterans by the N.C. Division, United Daughters of the Confederacy at Beech Gap, Haywood County, August 11, 1956, 2:30 PM,” Box 34, Record Group 5, Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.

45. John Parris, “Balsam Trees Whisper in Breeze, A Memorial to N.C. Men in Gray,” Asheville Citizen-Times, 10 August 1956, 1, 13.

46. John Parris, “Balsam Trees Whisper in Breeze, A Memorial to N.C. Men in Gray,” Asheville Citizen-Times, 10 August 1956, 1, 13.

47. Gary Everhardt to Catherine S. Richardson, 6 September 1979, Box 34, Record Group 5, Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.

48. It is not clear if the wooden sign was, in fact, installed, or, if it was, why or when it again went missing. The state chapter of the DAR, meanwhile, reported that similar DAR signage had been vandalized and stolen in recent years, and in most instances they decided that “it would be expensive and not in the best interest of the Society’s limited funds to replace them only to have them stolen again.” This suggests not only a reaction against Confederate memorials, but also the broader memorialization of military history. Mrs. Robert S. Hudgins, IV, to James R. Brotherton, 10 July 1979, Box 34, Record Group 5, Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.

49. While Coski makes a compelling argument for the particular moment in which the battle flag became a banner of segregationist causes specifically, Confederate memory has long been employed and invoked to support white supremacist positions, and many would argue, was the backbone of Jim Crow Era legislation and social conventions. John M. Coski, “The Confederate Battle Flag in Historical Perspective,” in Confederate Symbols in the Contemporary South, ed. J Martinez, Ron McNinch-Su, and William D. (William Donald) Richardson (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2000). See also: Charles Wilson, Baptized in Blood : the Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865-1920 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1980).

50. Florence Hague Becker (Mrs. William A.), “Address of Mrs. William A. Becker; President-General, National Society, Daughters of the American Revolution, State Conference,” Report of the Thirty-sixth Annual State Conference of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution of North Carolina, 3-5 March 1936 (Asheville, NC), 59.